On a cool September day, my co-intern and I drove the fifty miles on a dirt road to the Spotted Bear Ranger Station. The road follows the winding, rugged shoreline of the Hungry Horse Reservoir. Pulling into the station’s office, we noticed a fringe of orange flames burning lazily up the mountain. We wondered if we would still be able to stay at the bunkhouse that night. We soon learned that a prescribed burn was taking place, carefully planned around the several inches of rain predicted that night and the next day. The morning proved the weather forecast correct. A mist hung about the road as we drove past the ranger station the next morning on our way to Meadow Creek Gorge. The gorge is reminiscent of what the Hungry Horse landscape may have looked like before the reservoir, before the inundation of the long, steep valley carved by the South Fork of the Flathead River.

At Meadow Creek Trailhead, we spoke with a few visitors who had turned southeast, away from the gates of Glacier National Park, and towards the remote Bob Marshall Wilderness. One of the visitors, a fisherman, mentioned the beneficial impact of the Hungry Horse Dam in preventing nonnative fish from swimming upstream and degrading habitat for native cutthroat and bull trout. This comment, said in passing, catalyzed a world of exploration for me as I delved into the dam’s history and ecological impact.

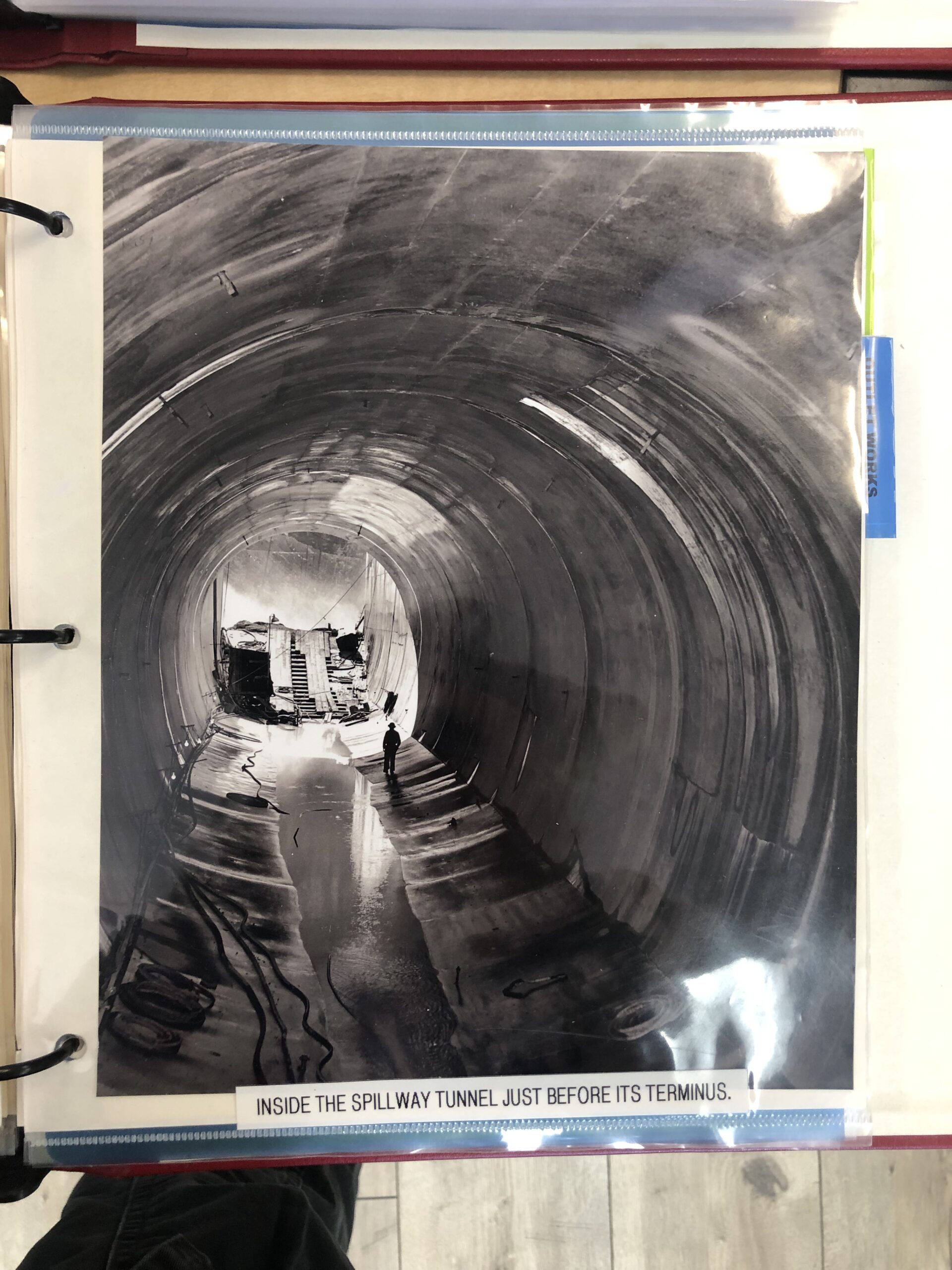

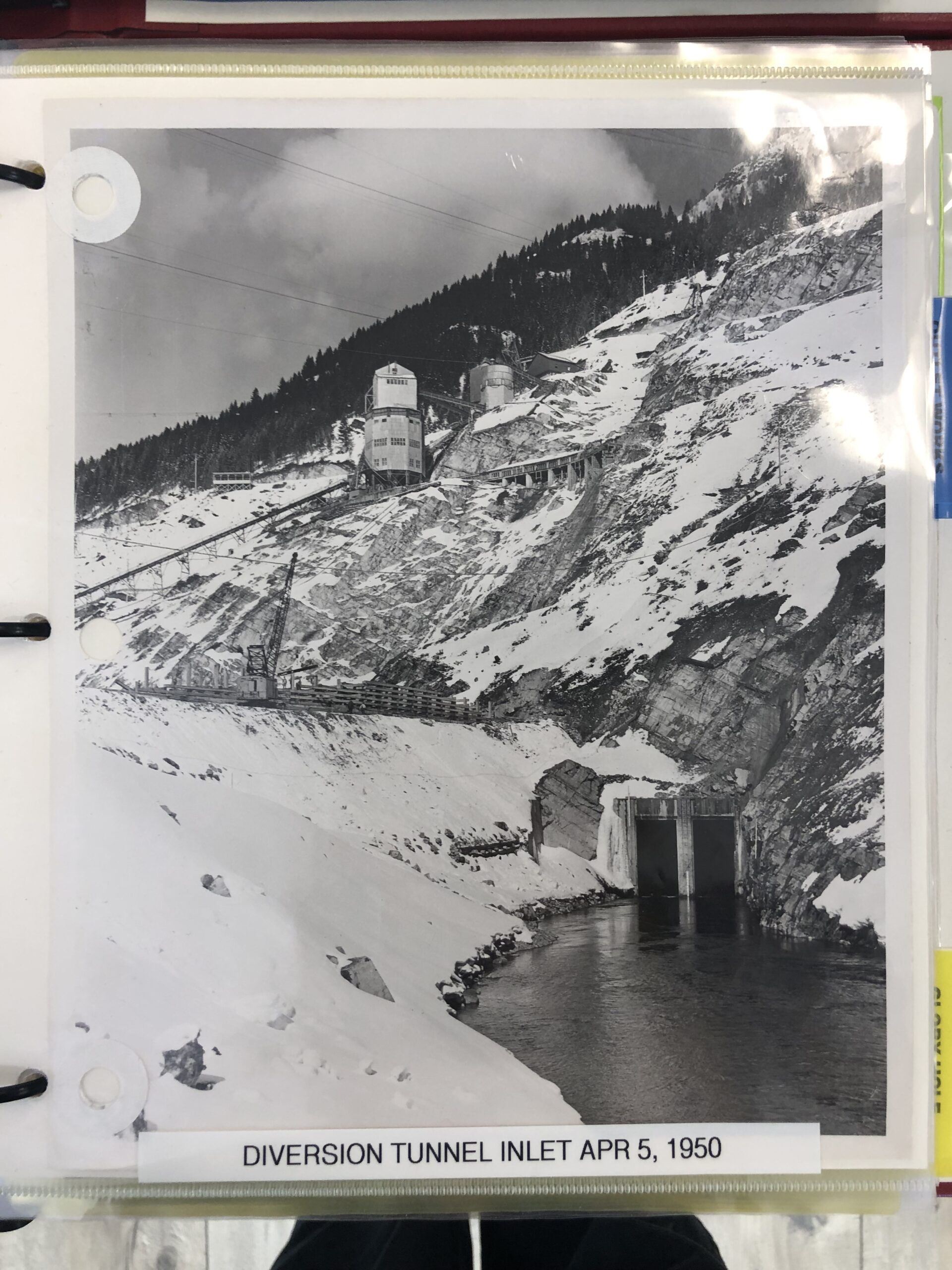

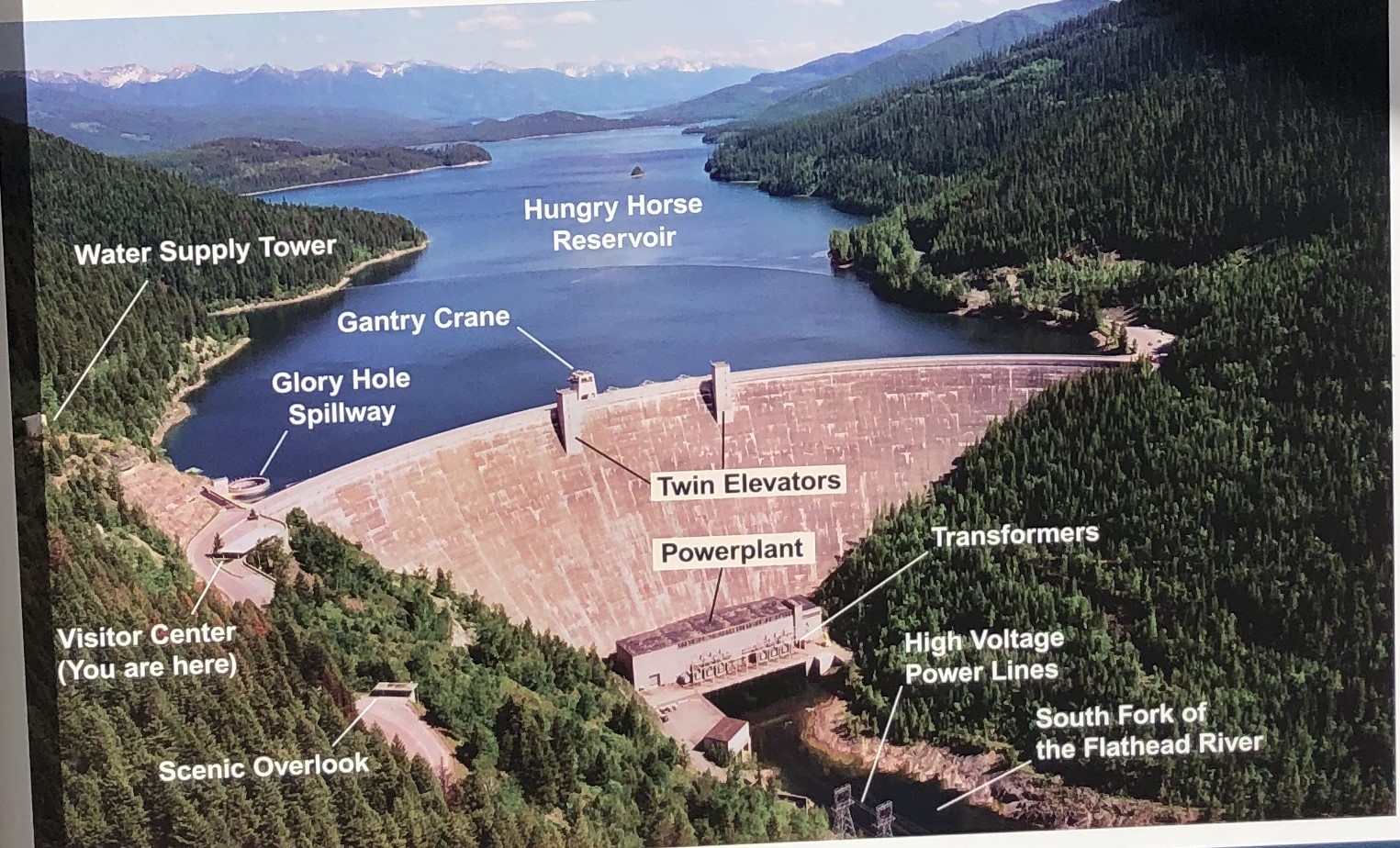

On our next trip down to Spotted Bear, we stopped at the dam’s visitor center, perched halfway up the steep mountainside, along the road that runs overtop the dam. A sign in the art deco style of “The Big Dam Era” — in its heyday from the 1930s to 1960s (Lee 2023) — announces the dam. Finished in November 1953, the Hungry Horse Dam was a crowning achievement of the era. Standing at 564 feet, it was the second tallest dam in the world at the time of its completion (McKay 1994). Black and white photographs in the visitor center document the larger-than-life engineering feat of the dam’s construction. Tiny figures of men stand in miniature within the 12-foot diameter spillway tunnel. Yet these men moved mountains, blasting a tunnel through the adjoining rock wall to divert the river during dam construction.

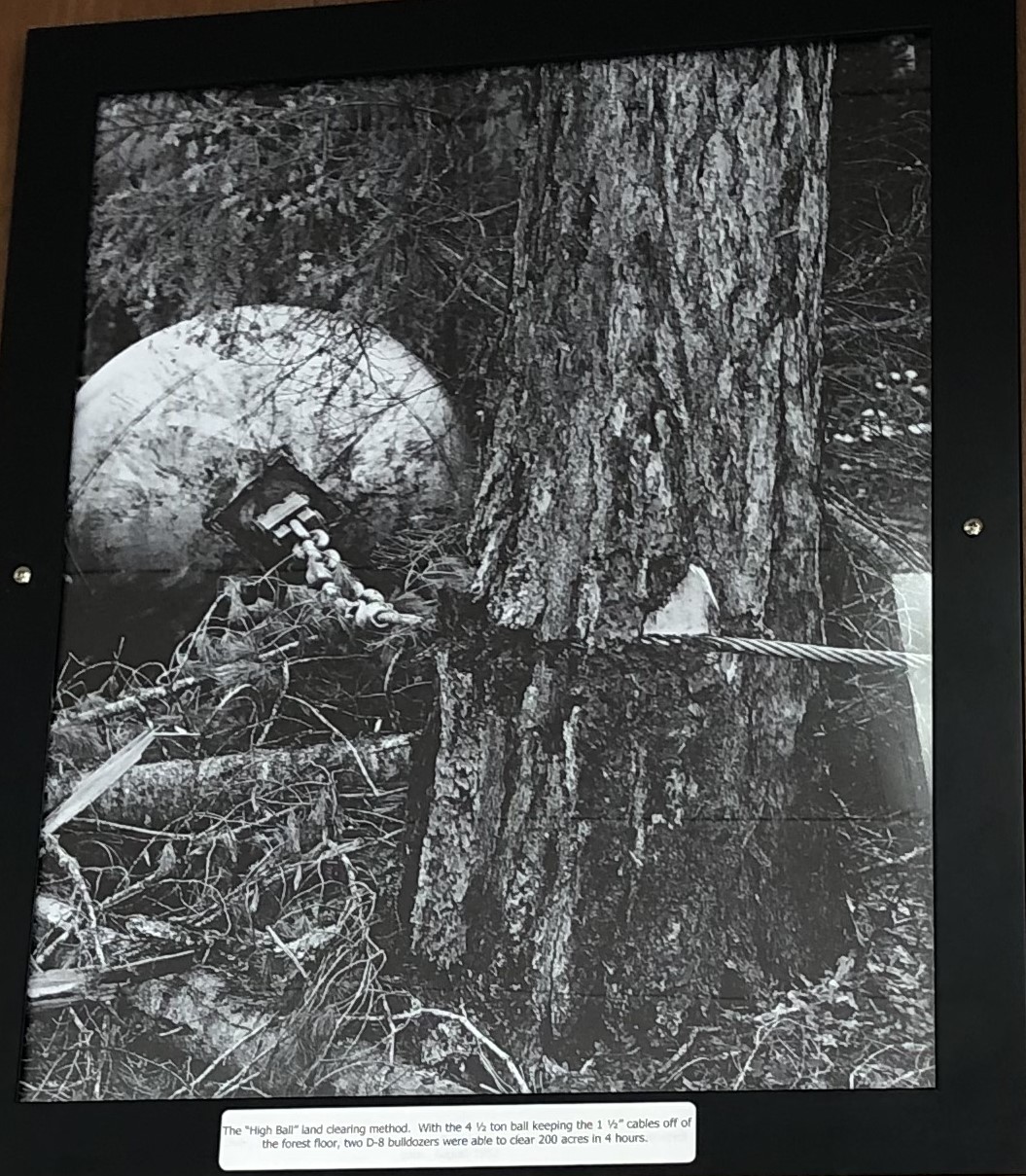

The little town of Hungry Horse, still standing today, sprung up to support the laborers. The town and dam are named after an incident in the winter of 1900. Two men hauling equipment over the South Fork of the Flathead River noticed, after the river crossing, that two of their horses, Jerry and Tex, were missing. A month later the horses were found “belly deep in snow and nothing but skin and bones” (Stene 1995). The horses were nursed back to strength and lived out their days in nearby Kalispell, but the area bears witness to their hungriest hour. A large steel ball, painted a garish silver, stands as a mysterious testament to the town’s origin. The dam building started not with pouring the dam’s concrete but with clearing trees from the flow area to limit debris in the reservoir. (Grant 2018). Several logging companies took up the herculean task of clearing the 37 square miles of land in the reservoir’s path (McKay 1994). The large steel ball standing in Hungry Horse today was used in the “highball” clearing method that could clear 200 acres in 4 hours (McKay 1994; Grant 2018). The ball, 8 feet in diameter and 8,000 pounds in heft, was not a wrecking ball but rather a weight (Shaw 1967). A long cable, secured between two bulldozers and held fast at the center by the heavy ball, was used to drag down and uproot trees. Using this unusual method along with more conventional methods, loggers harvested 90 million board feet of timber from the area in just a few years (Grant 2018).

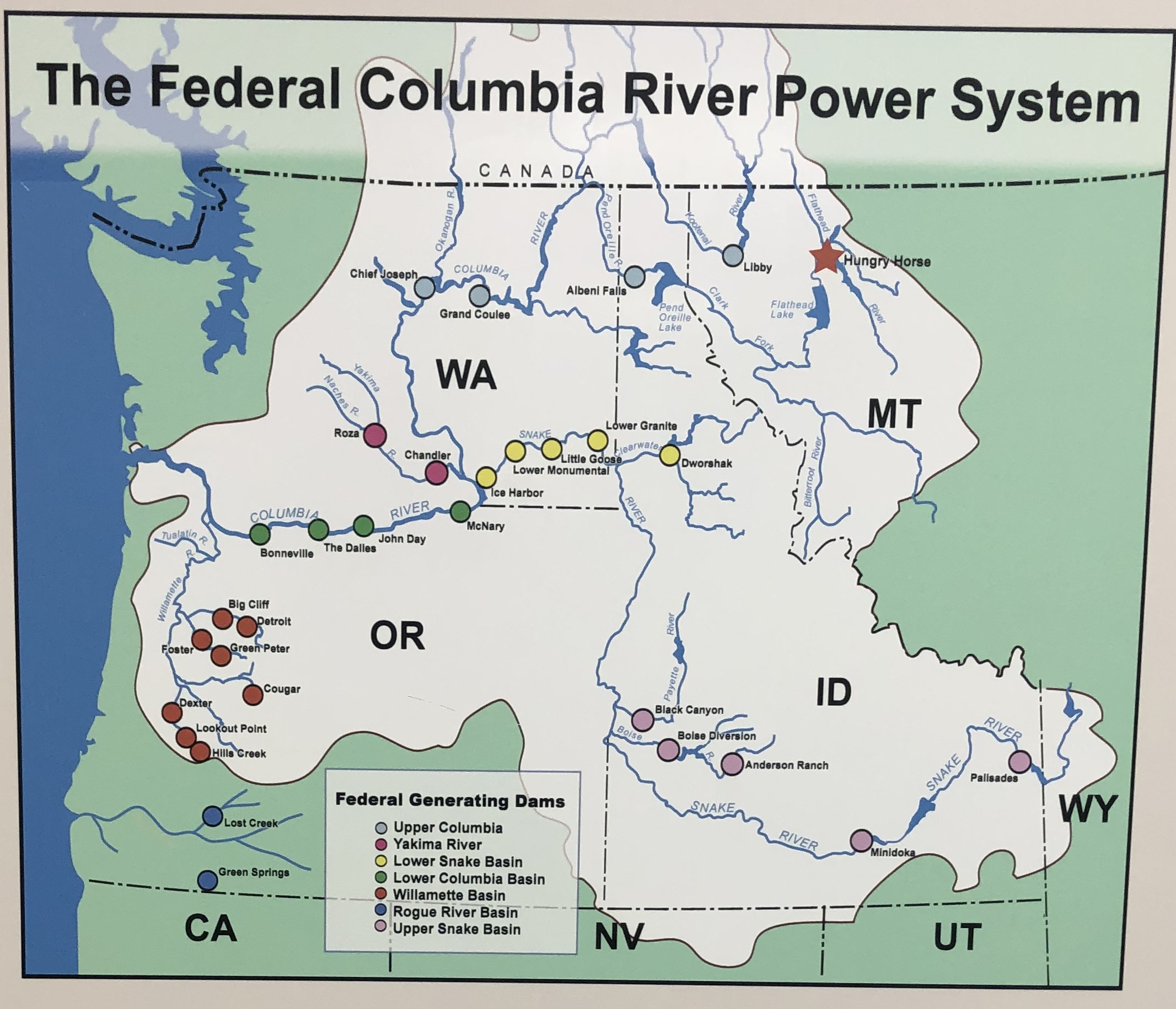

Once completed in 1953, the dam backed up the South Fork of the Flathead River for 34 miles and flooded about 22,500 acres of land (McKay 1994). Today, the dam still fulfills its original purpose, generating electricity, regulating water flow for flood mitigation, and acting as water storage for downstream dams in the greater Columbia River Basin system. The Hungry Horse reservoir is one of two other headwater reservoirs for the Columbia River Basin, the other being the Koocanusa Reservoir in the adjacent Kootenai National Forest. Together, these two reservoirs provide approximately 40% of the usable water storage in the U.S. portion of the Columbia Basin (Muhlfeld, 2012). The Hungry Horse dam impacts both local and regional ecosystems, since water from the reservoir travels more than 1,100 miles from Montana’s mountains to the Pacific Ocean. Some of those impacts are obvious, like the creation of a lake from a river. Other impacts are less so.

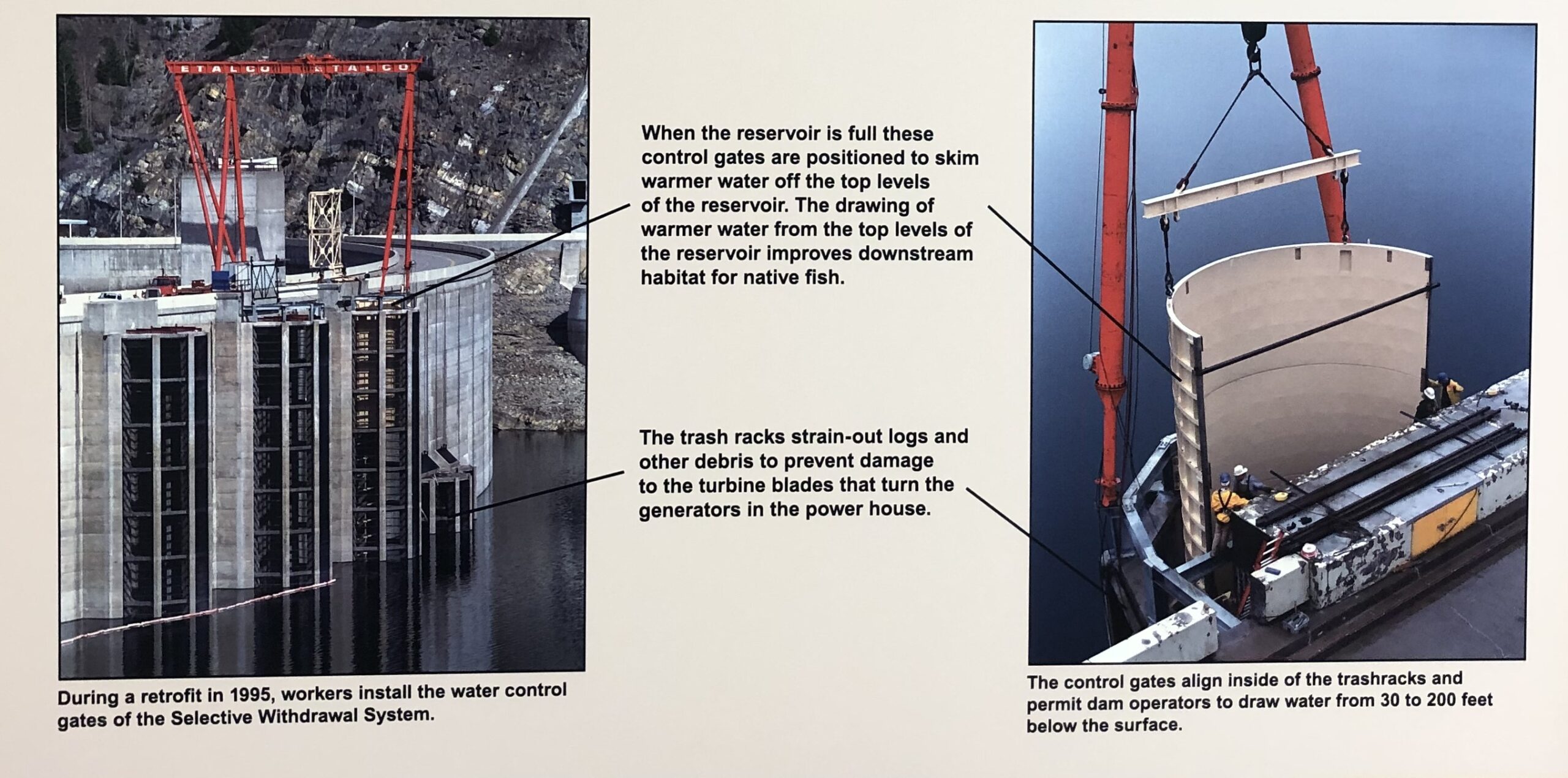

The dam’s four penstocks (gates that direct water to the turbines) are located 241 feet below the reservoir level. Water at that depth maintains a year-round temperature of about 38F, which is quite a bit colder than summer surface temperatures of up to 68F (Christenson et al., 1996). Biologists speculated that the dam’s cold-water discharge would modify the downstream river ecology (Christenson et al., 1996). By the 1980s, biologists with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks were recording falling native trout populations, stunted trout growth rates, and changes in the trout’s prey, macroinvertebrates. They also found unusually large numbers of cold-water lake trout in the Flathead river’s main stem. The cold water offered an ideal habitat for the voracious lake trout which fed with abandon on juvenile cutthroat and bull trout (Cristenson et al.,1996). The food web was changing. To combat these effects, the discharged water needed temperature control (Standford et al., 1992). A “Selective Withdrawal System” was installed in August 1996. The system placed 100-foot-long selective depth outlet structures over the penstocks. Warm surface water could be skimmed off the top of the reservoir and mixed with cooler water anywhere from 30 to 200 feet below the water’s surface. Electronic temperature sensors ran the length of the structures and informed which outlets to open and close to produce the required water temperatures. The system is still in use and begins operations each year in June after spring runoff flows reduce and continues until October. The release of warmer water during the biologically productive summer months has eliminated the artificial cooling of the river and returned it to its pre-dam annual temperature cycle (State of Montana, 2014).

In the almost 30 years since its installment, the selective withdrawal system has measurably affected the surrounding ecosystem. Eliminating cold discharges during summer appears to have restricted the movement of non-native lake trout upstream from Flathead Lake (Muhlfeld et al., 2012). Studies on macroinvertebrate populations are mostly inconclusive though there are some signs of slightly improved benthic macroinvertebrate assemblages in the South Fork River, downstream of the dam (Richards, 2010). The selective withdrawal system allows some aspects of the downstream river to return to pre-dam conditions, but other aspects cannot be so easily turned back. Flow regulation for flood control and power generation has resulted in an inversion of the natural hydrograph; water storage during spring keeps run-off low and release of water during summer, fall, and winter keeps flows unnaturally high (Muhlfeld, 2012). The current flow management strategy simulates natural flow conditions to maximize bull trout habitat in the South Fork of the Flathead River by keeping flows lower, but flows must still remain artificially high to augment flow for anadromous fish recovery hundreds of miles downstream, in the lower Columbia River Basin (Muhlfeld, 2012). Caught in a web of ecological consequences, changing one thing then affects another, achieving all pre-dam conditions is elusive. Can a controlled river really be made to mimic a natural river?

The visitor’s passing comment about one of the beneficial effects of the dam is true; the dam has proven an effective barrier against nonnative fish. The South Fork River upstream of the Hungry Horse Dam contains one of the largest self-sustaining populations of westslope cutthroat trout in existence (Marotz et al., 1996). The reservoir also supports a stable bull trout population, which can be attributed to the relatively undisturbed spawning tributaries in the Bob Marhsall Wilderness upstream of the dam (Marotz et al., 1996). Moreover, the dam provides clean, renewable energy, critical as we try to slow down human-caused climate change. Yet, by removing the historical disturbances of flood and drought cycles through flow regulation, the biological characteristics of the downstream Flathead River have been altered (Schmutz and Moog, 2018; Muhlfeld, 2012). And, of course, the reservoir itself has buried an entire landscape and its local ecosystem under hundreds of feet of water. The Hungry Horse dam created a new ecosystem while also preserving some aspects of the past ecosystem. Some impacts of the dam can be mitigated, while other impacts require adaptation in human, animal, and plant lifestyle.

References

Christenson, D. J., Robert L. Sund, and Brian L. Marotz. “Hungry Horse Dams successful selective withdrawal system.” Hydro Review 15.3 (1996).

Grant, James A. “Historic Logging Uses and Timber Management at Hungry Horse Reservoir.” U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. (2018). https://www.bpa.gov/-/media/Aep/environmental-initiatives/cultural-resources/historic-logging-uses.pdf

“Hungry Horse Reservoir, Montana: Biological Impact Evaluation and Operational Constraints for a proposed 90,000-acre-foot withdrawal.” State of Montana. September 14, 2011. https://dnrc.mt.gov/_docs/water/Appendix_8_StateBiologicalConstraintsMemo.pdf

Lee, Gabriel. “Overview: The Big Dam Era.” Energy History Online. Yale University. (2023). https://energyhistory.yale.edu/the-big-dam-era/.

Marotz, B. L., et al. “Model development to establish integrated operational rule curves for Hungry Horse and Libby Reservoirs—Montana.” Report to the Bonneville Power Administration. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, Kalispell (1996).

McKay, Kathryn L. “Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800–1960.” Flathead National Forest. (1994). http://www.npshistory.com/publications/usfs/region/1/flathead/history/#:~:text=TRAILS%20OF%20THE%20PAST:%20Historical%20Overview

Muhlfeld, Clint C., et al. “Assessing the impacts of river regulation on native bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) and westslope cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii lewisi) habitats in the upper Flathead River, Montana, USA.” River Research and Applications 28.7 (2012): 940-959.

Richards, David C., and Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. “Possible effects of selective withdrawal-temperature control at Hungry Horse Dam, nuisance growth of Didymosphenia geminata, and other factors, on benthic macroinvertebrate assemblages in the Flathead River.” Report to Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, Kalispell MT (2010).

Schmutz, Stefan, and Otto Moog. “Dams: ecological impacts and management.” Riverine ecosystem management: Science for governing towards a sustainable future (2018): 111-127.

Shaw, Charlie. “The Flathead Story.” USDA Forest Service, Flathead National Forest. (1967) http://www.npshistory.com/publications/usfs/region/1/flathead/story/index.htm#:~:text=THE%20FLATHEAD%20STORY.%20By.%20Charlie%20Shaw.

Stanford, Jack A., and F. Richard Hauer. “Mitigating the impacts of stream and lake regulation in the Flathead River catchment, Montana, USA: an ecosystem perspective.” Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2.1 (1992): 35-63.

Stene, Eric A. “Hungry Horse Project.” U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. (1995) https://www.usbr.gov/projects/pdf.php?id=125