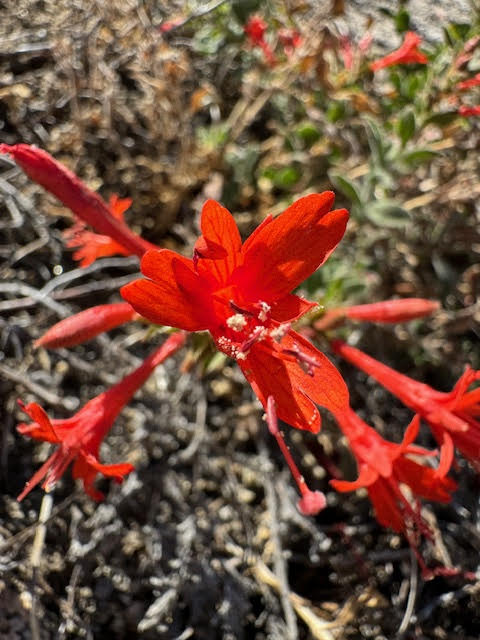

Oak woodlands are one of California’s most important habitat types, “have[ing] higher levels of biodiversity than virtually any other terrestrial ecosystem in California.” (Elizabeth A. Bernhardt and Tedmund J. Swiecki, 2019). As intense wildfire continues to drive type conversion, with many of our old growth oak woodlands slowly being converted to invaded grasslands, there is a clear need to include trees into restoration strategies in addition to shrubs, sub-shrubs, and native grasses that are common in many of our revegetation efforts.

Oaks trees, dependent on species, produce acorns in large amounts irregularly (every other year to as many as every 4 years), these large crop events are known as mast years. This year happens to be a mast year for many oak trees in the red oak group, including Black oak (Quercus kelloggii) and Canyon live oak (Q. chrysolepis). These are two of the dominant oak species on the San Bernardino National Forest (SBNF). Due to this increased production of acorns this year, it has been a restoration priority to collect as many as we can while the crop is so bountiful.

Collecting acorns comes with its own unique challenges compared to other seeds I have collected throughout this field season. For starters, oak trees get tall. The trees with the most acorns are the oldest and largest and thus they dangle this precious restoration resource high above the forest floor. Unless you happen to have some stilts or a giant on your restoration staff you have to get a bit creative in how you overcome this challenge. On our team we decided the best strategy for acorn retrieval was to start by finding the longest stick available, that could be the end of a rake, a hula hoe, or a branch. This stick served one purpose, to shake acorns from the high branches we mere humans could not reach on our own.

A second challenge in acorn collection, at least in the SBNF, is Phytophthora. In order to prevent introducing this plant pathogen into our nursery stock we never collect seed that has already fallen to the forest floor. This meant we could not just shake branches and pick up what fell to our feet. Instead, we spread out a large tarp beneath the oak tree canopy and caught as many of the falling acorns as we could before they hit the floor beneath us. It often felt like this could be a new mini game in the next Mario Party (or does this already exist? If not it should, Nintendo call me).

Now lets not forget the fact that acorns are not just used by restoration teams like the one here at the SBNF. There is also the challenge of competition for this limited resource with the native residence of the forest. Tree squirrels love acorns for they are packed with energy and can be easily eaten in half the time as harder nuts. They also bury and store a large amount of the acorns they collect, making them perhaps natures original restorationists.

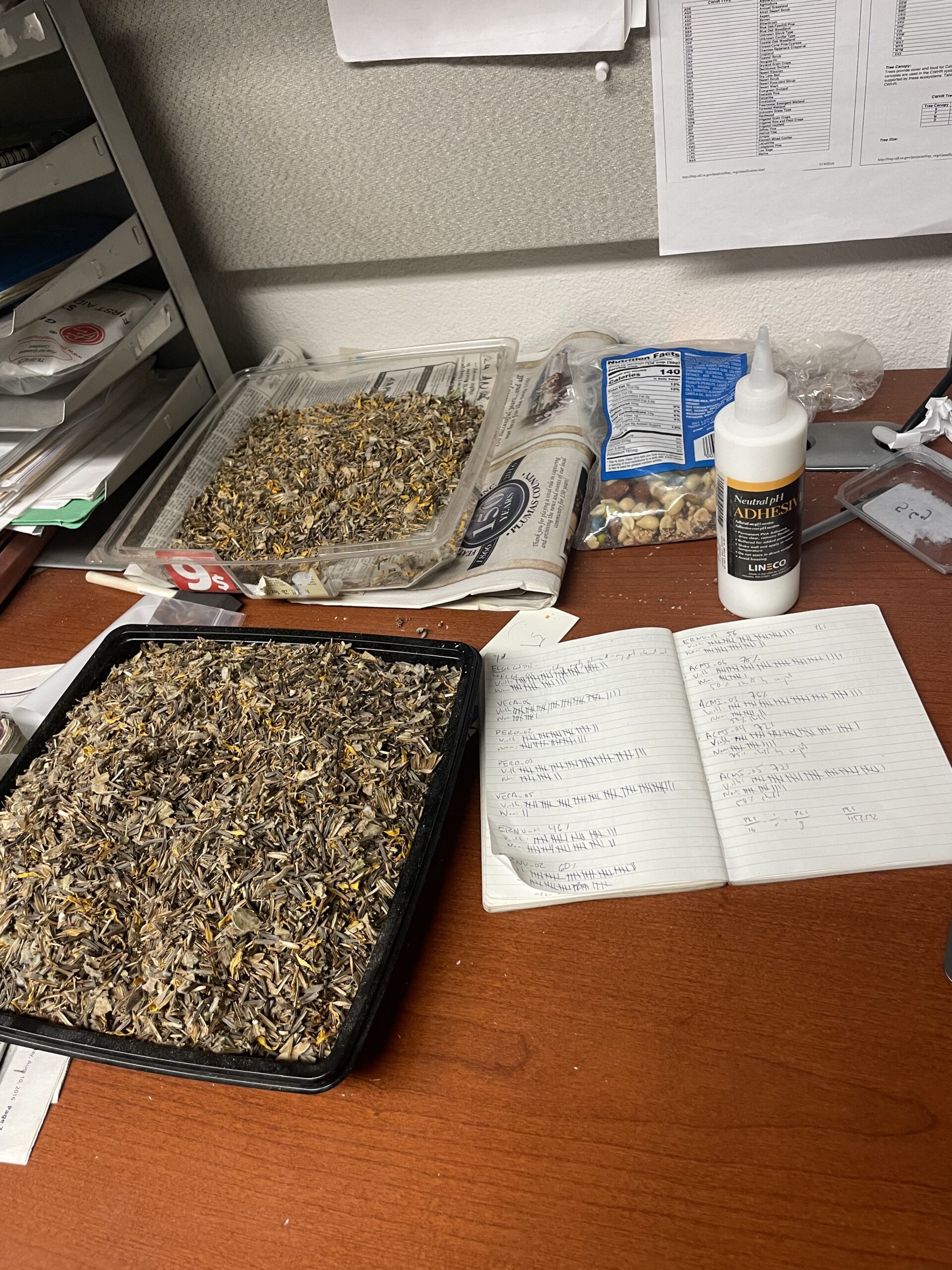

We also compete with less furry creatures that use acorns for their nutritious insides, acorn weevils. Acorn weevils lay their larvae inside of, you guessed it, acorns. A clear tell that an acorn may be home to a growing larvae is a small circular exit hole somewhere on the exterior of the acorn. Squirrels and other forest animals often leave these damaged acorns behind and by the time we reach the oak trees a large amount of what remains may be already occupied by these larvae. At some point Jorge, my cabin mate at the Forest Service barracks, and I found countless larvae on the dinner table after storing an acorn collection bag there overnight before bringing them into our main office, not a fun discovery first thing in the AM.

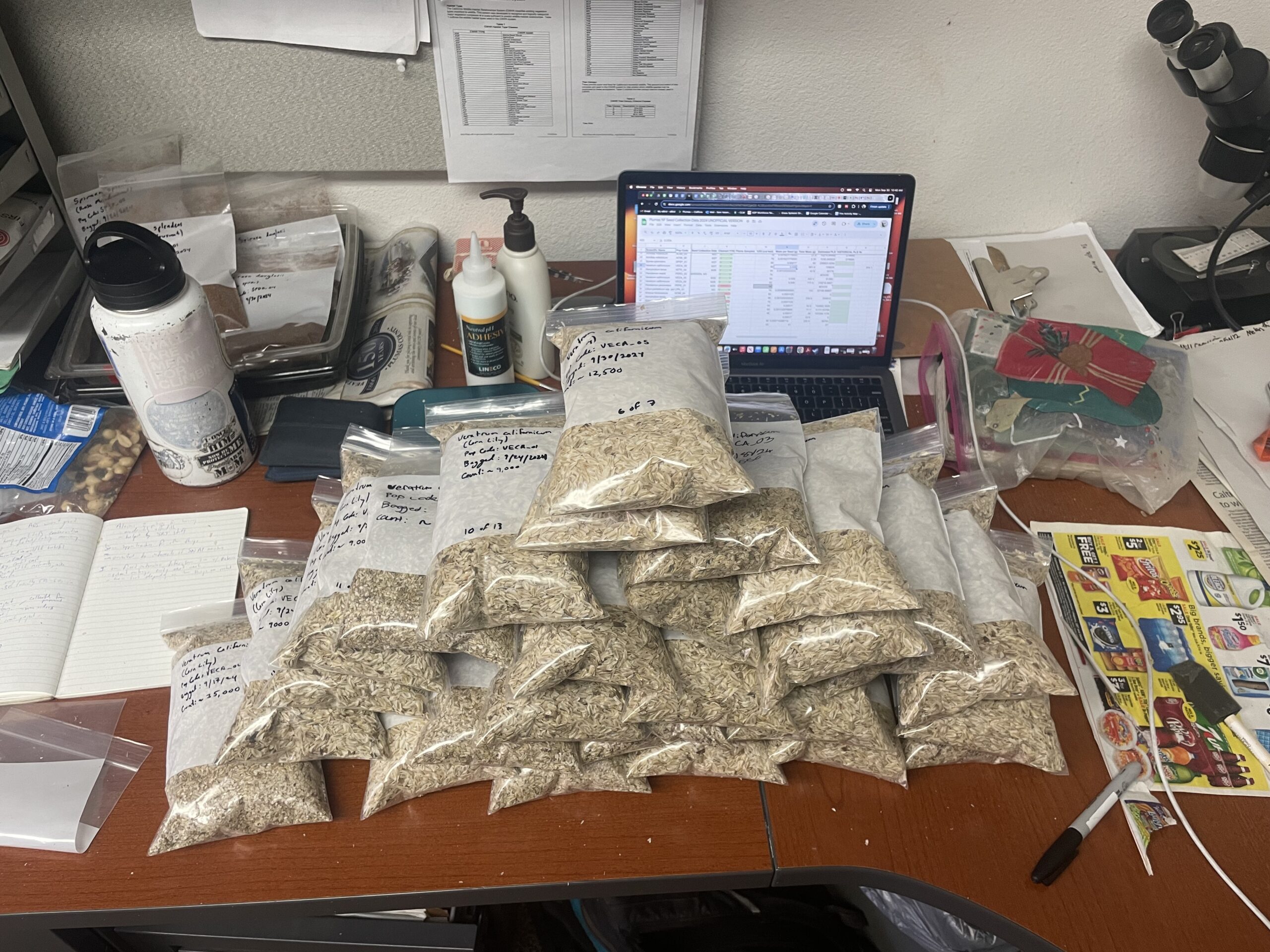

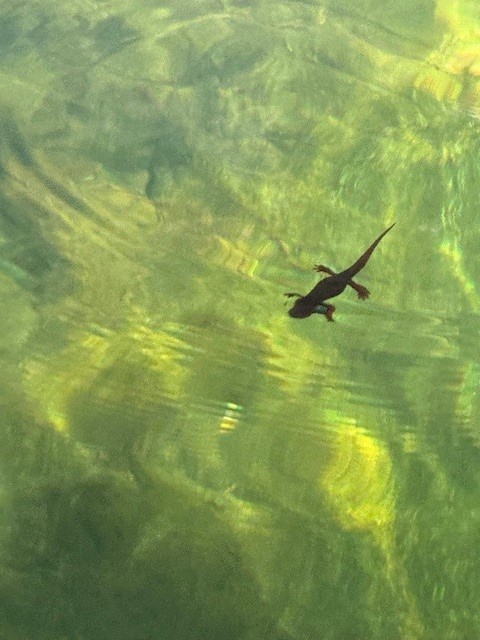

In order to sort out damaged acorns from those acorns that have the highest probability of germinating, a common strategy used is a float test. A float test is pretty much what it sounds like, a container is filled with water and acorns are added in with some floating to the top and other sinking to the bottom of the container. Those acorns that float are usually lighter due to some damage to the oak embryo inside. Heavy full acorns are usually full of the nutrients needed to support a young oak seedling early in its development. Therefore, the floating acorns were skimmed off the top and disposed of with only the sinking acorns being utilized in our final collection. Additionally, any acorns that sunk but had any visual signs of weevil damage (i.e. clear exit holes) were removed from our final collection.

Overall, our acorn collecting efforts so far this year have felt like a success. For the end of my time at the SBNF we will be cleaning, weighing, and assigning accession numbers to our final seed collections including all of our precious acorns. So, TBD (to be determined) on the final weights of our acorn collections. It feels like my time here at the SBNF has flown by and I am not ready to say goodbye to this beautiful place. But, alas, all great things must come to an end. For now I am just cherishing each day and trying to learn as much as I can as I begin searching for what will be coming up next for me. I know the first hand experience and connections I have gained through the CLM internship experience will help give me the ability to excel in whatever natural resources position I put my efforts toward in the future.