As the weather starts to get colder, plants around Plumas National Forest have matured seed and are mostly now beyond the window of collection. This is not a problem for us as we’ve successfully collected from all of our target populations! Besides a couple of final population checks, September has been characterized by time in the office, preparing all of our seeds for their hopefully big and bright futures.

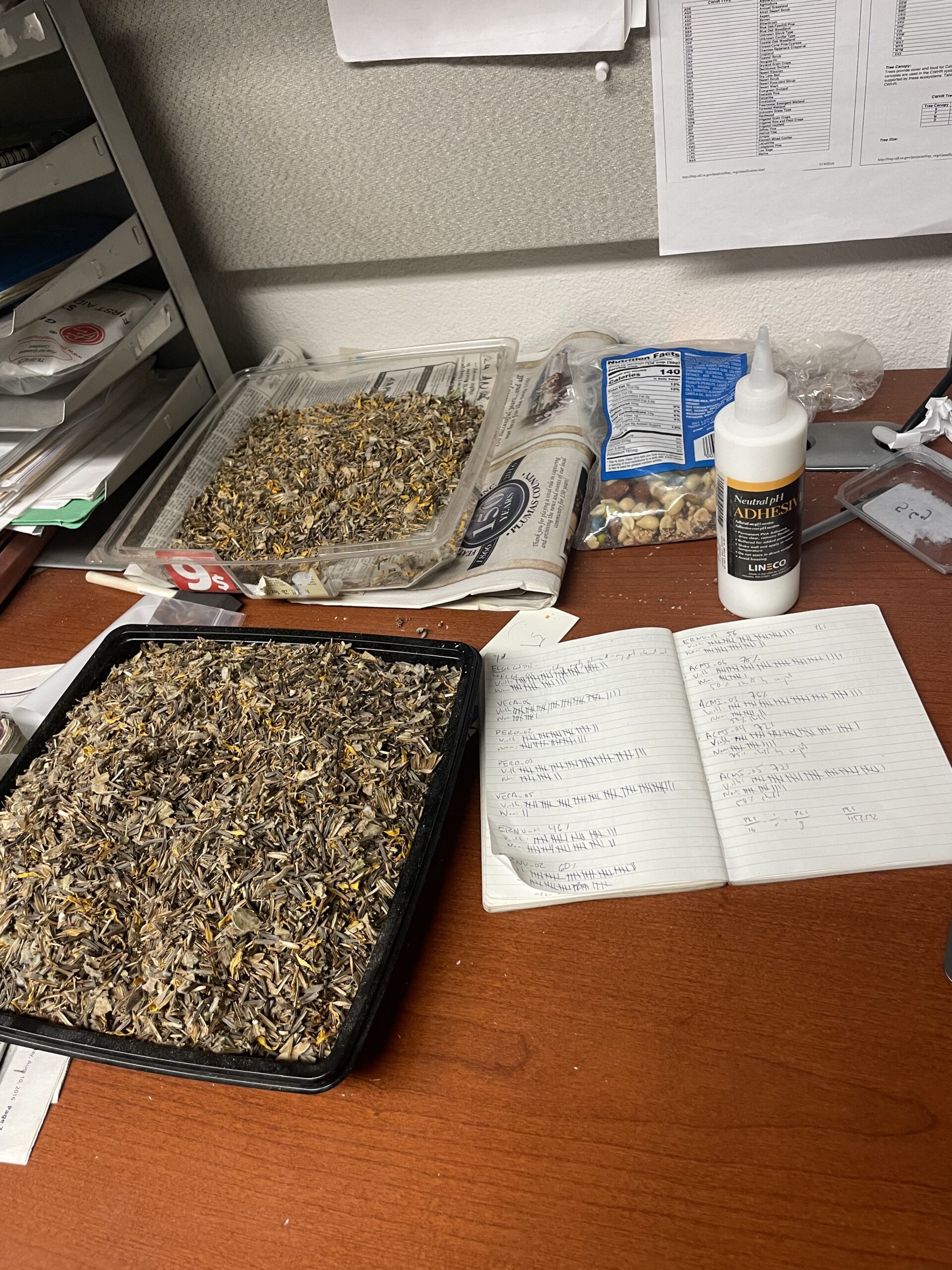

As we had some of the materials and certainly the time, our mentor thought it would be best for us to clean the seeds ourselves rather than send them to an extractory like Bend. There was a lot to go through, but I agreed it would be a good experience and satisfying to participate in another section of these seeds’ journey. Due to the dry environment here, we left all the cleaning to be done at the end of the season. Collected seeds were stored with their chaff in paper bags around the office and did not seem to be impacted by mold or too much additional pest pressure. This meant that at the start of September, we had a mountain of work to do.

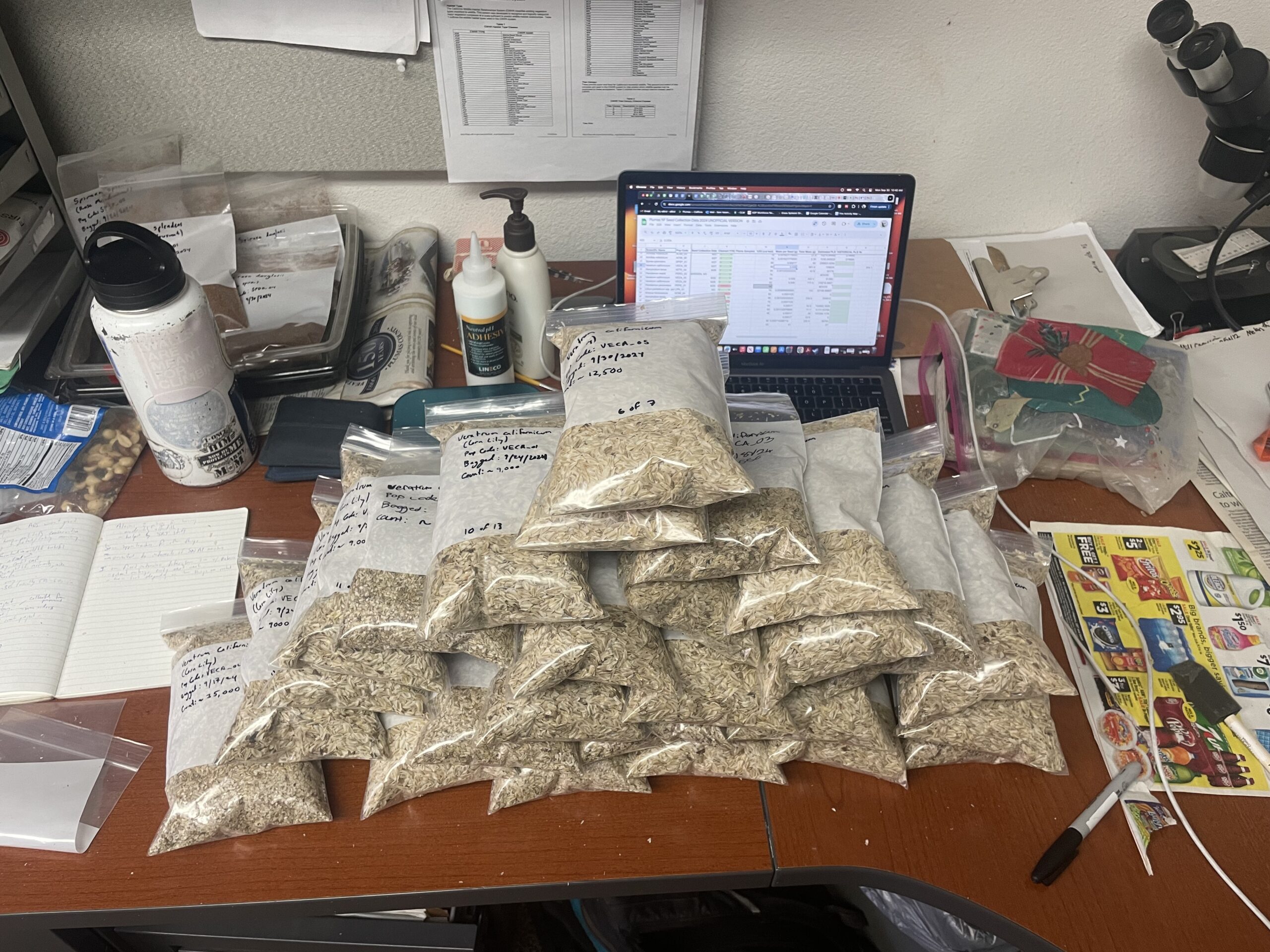

For most species, the bulk of the cleaning was done using four different-sized, specialized seed-cleaning sieves. Taking the seeds and the sieve to a picnic table outside, we would run everything through the sieves until most of the chaff that weren’t the same size as the seeds, were filtered out. From there, relying on the predictable early afternoon breeze, we would pour the remaining seeds and chaff from one container to another to blow away the excess. Typically, the chaff is lighter than the seeds so it would be caught in the wind and blow outside the confines of the container while the seeds would fall straight down. However, we had to be careful as an occasional strong gust of wind could blow everything away. Once the seeds were filtered to a satisfactory level (nobody’s perfect), we transferred them to a sealable plastic bag for longer term storage. Next the bags were weighed and PLS estimates were generated using our cut test data, single seed mass, and bag weights adjusted for the amount of chaff still remaining. These bags will soon go into storage and hopefully be used in restoration projects in the near future!

Besides seed cleaning, there were other various office tasks to be done. Bit by bit, we had been mounting our voucher specimens, organizing our data, and slowing assembling our final report. Office days feel much longer than field days, and I certainly miss going out into the woods to explore on such a regular basis. But the organizational side of me enjoys checking off to-do lists and slowly filling out the all-important data sheet entitled: “Plumas NF Seed Collection Data 2024 UNOFFICIAL VERSION”. Official version soon to come. As I am writing this, the checklist is almost complete and the spreadsheet is almost filled. This chapter is coming to a close. It may be sad to leave but I am excited for the next adventure.