Greetings,

In my first post, I mentioned going to the Brokeoff Mountains to look for Dermatophyllum guadalupense. Since then, I have digitized some old survey maps for this species and, with Mike Howard, further explored its distribution.

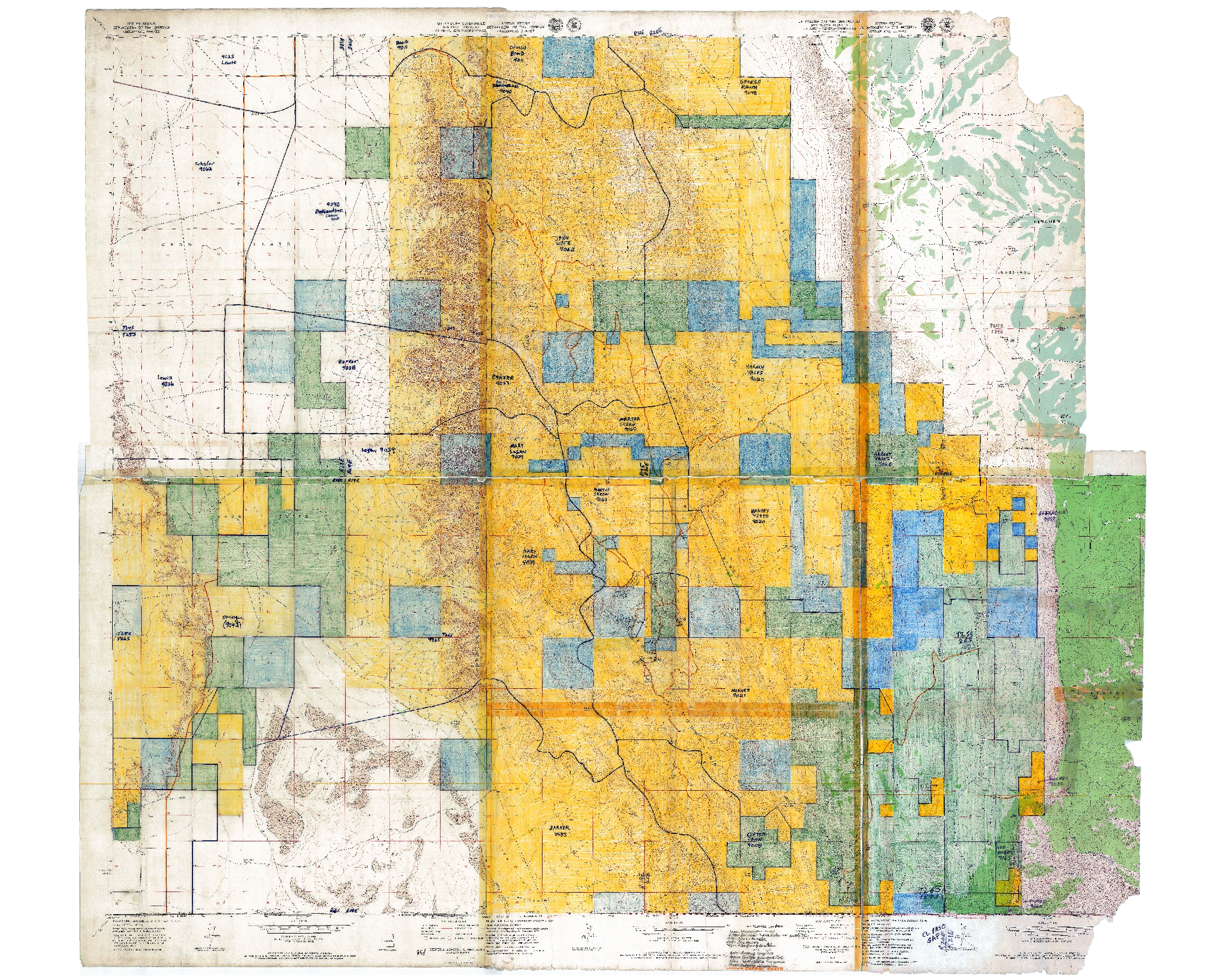

The Las Cruces District Office of the BLM funded some survey work for Dermatophyllum guadalupense in the late 1980’s. This being a while ago, there was no GIS. There were GPS units, barely, but they were big, heavy, expensive, and rarely used by biologists. So plant surveys were done the old-fashioned way. Head outside with USGS topo maps, wander around looking for plants, do your best to match up your wanderings and plant observations with the topos, and write on the maps. So we have an old survey map for Dermatophyllum guadalupense. It’s a set of USGS 1:24,000 topographic maps, cut and taped together to cover the survey area, hand-colored (with crayon, so far as I can tell) to show land ownership, and annotated by hand to show survey routes and locations of plants. Given the modern capabilities of GPS units and GIS software, it is amazing that this approach was state-of-the-art so recently. But, if you knew what you were doing—and the botanist, Phil Clayton, did!—it worked pretty well. So, now, we can scan the map, georeference it, and display it in ArcGIS. Here’s the map, at its full extent:

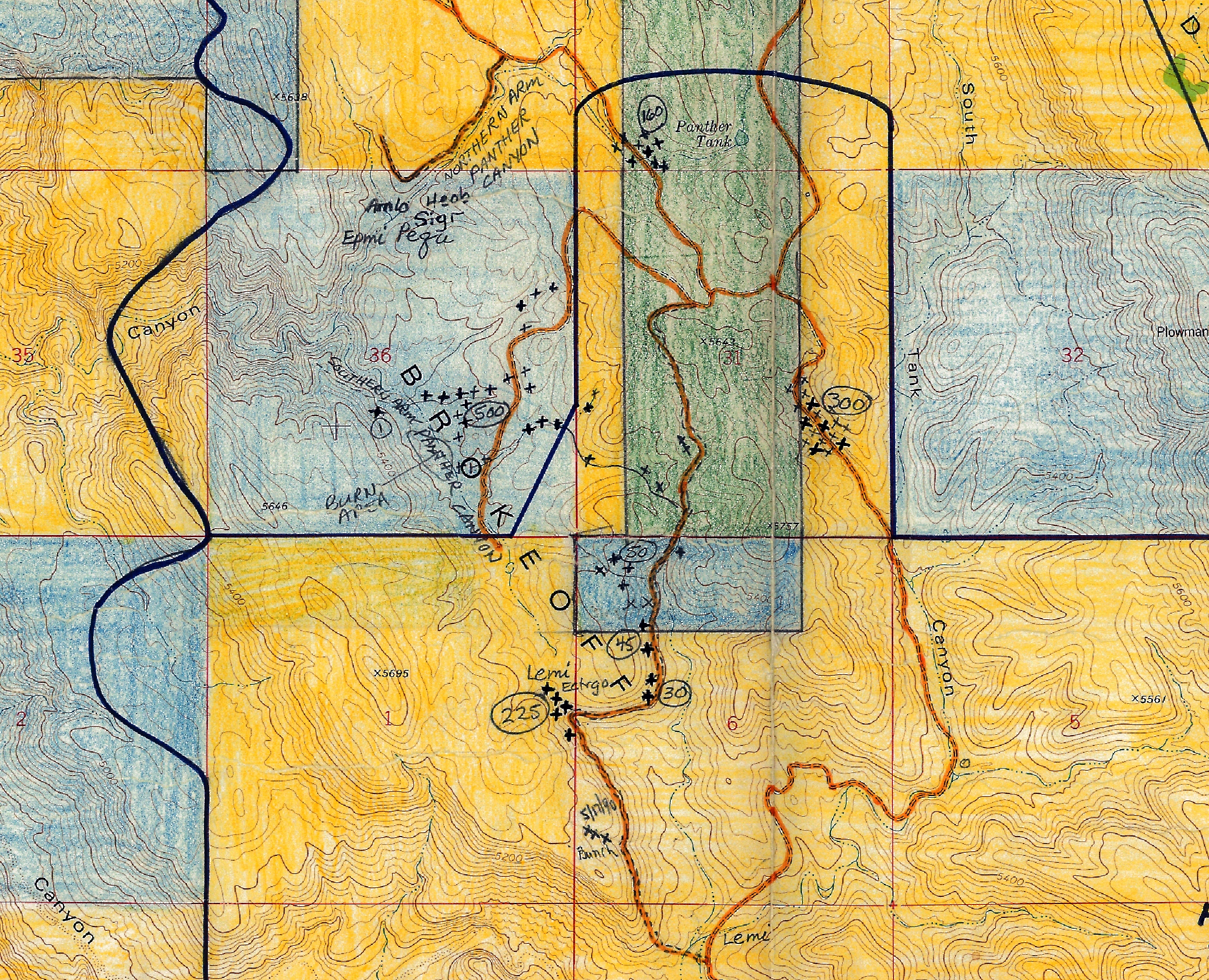

And here’s a portion of it, zoomed in to show plant locations:

I’ve georeferenced the map, so that it can be displayed in ArcGIS and viewed with other layers. This is a surprisingly straightforward process; basically, you load the scanned image in ArcGIS and then georeference it by clicking on points in the map, then clicking on the same point in a reference layer (for which I used previously scanned and georeferenced USGS topos in the LCDO’s GIS drive—since my reference layer is the same as the scanned map, except for the hand-colored land ownership and plant survey data, this is easy). So now we can look at the old survey map in a GIS context, compare it to aerial imagery, put coordinates on the surveyed plant locations, go outside and know we’re looking at the same place Phil Clayton did 25 years ago, and so on and so forth. Cool!

However, Phil Clayton did not get everywhere and survey everything. Mike Howard found some locations for Dermatophyllum guadalupense that are not in that map. He found three more plants near the end of a road that leads to a livestock water storage tank and had previously looked northwest of the tank, not finding any more Dermatophyllum guadalupense. So, on the third of July, we went out and, this time, wandered southeast of the tank. The short version is: we did not find any more Dermatophyllum guadalupense. But, we got to go outside and examine the area:

We also found another rare plant, Ericameria nauseosa var. texensis:

And Echinocactus horizonthalonius was flowering:

And whiptails (in this case, Aspidoscelis tesselata) were out:

Also, if you were wondering what Dermatophyllum guadalupense looks like, well, here it is: