In southern Alaska, Colorado’s aspens and canyons are replaced by yellow and red cedar, by spruce and vast ocean. Utah’s diverse plant life – small geniuses in the art of conserving water – exchange places with green ferns and mossy forest floor, well-acquainted with rain and hungry for speckled light that dances slantways through dense canopy. Here, in southern Alaska, bald eagles attach to telephone wires, and locals are accustomed to the great bird’s presence. Bears follow your scent and encourage you to maintain conversation between field partners, to keep your eyes alert and to pay attention. Boats are about as common as cars for transport, and the concept of vast and grand exceed their common definitions.

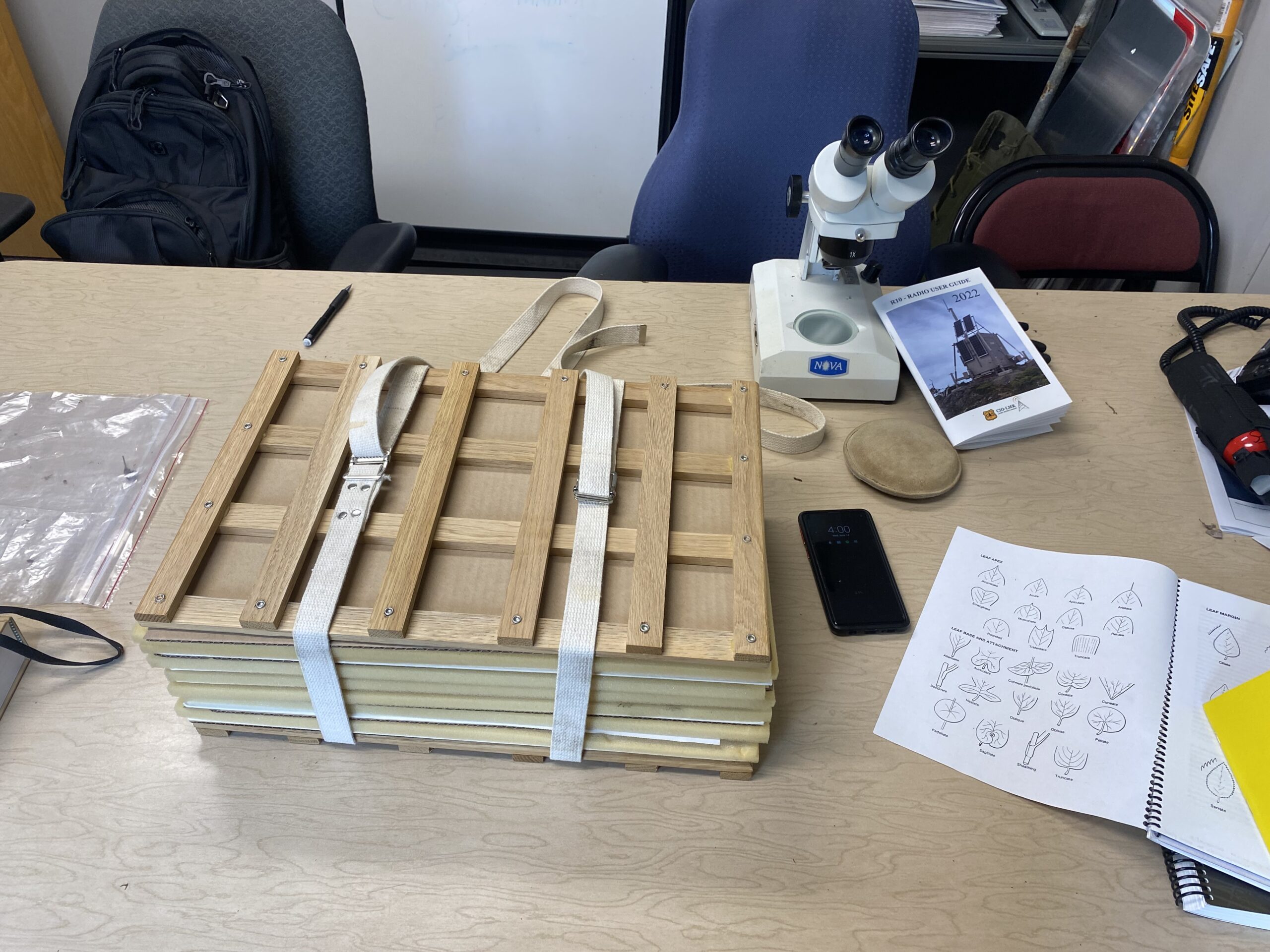

Working on the Tongass National Forest this past month has meant a lot of different things. My field partner and I spent many days scouting and vouchering at potential seed collection sites, and there we collected data on the various native plant species in the area – their phenology, their population density, when we can anticipate they will go to seed. We helped out on a stream restoration crew, jamming logs into stream banks to restore meanders and a diversity of water-flow and attempt to build back habitat for spawning salmon. On one Saturday, I helped local kids paint imprints of salmon on blank T-shirts. On other days, we spent time training in safety protocols and herbicide use. We visited timber-harvest sale areas and while they looked at the trees, we looked at the understory with an eye out for anything rare, or lacking in abundance.

While doing so, I have learned several things:

- Plants, being immobile, have one of the broadest ranges of living beings.

- Muskegs are the definition of the abundance of the small.

- Skunk cabbage can grow taller than me, and spread wider too.

- While plants in the desert might be smart in the conservation of water, plants in the rainforest know how to use water to their full advantage.

- Rare plants, when you find them, feel like the most precious thing in the world.

- Everything, that is, everything… is slippery.

Each of these lessons stem from impactful experiences, yet perhaps the most impactful moment for me on the job this month occurred when we were conducting rare plant surveys and monitoring projects. While attending a forest-wide botany training on Prince of Wales Island – a remote four-hour ferry ride from our home Ranger District in Ketchikan – one of these rare species we were surveying and monitoring for was Yellow lady’s slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens). Often only showing a small, lush leaf or two, the elegant and plump lady’s slipper hides among large ferns and nestles in muskegs. She revels in the company of grasses and is what we call a “roadside rare.” How strange that such a scarce plant tends to grow best along the marginal edge of gravel roads. There are only four documented clusters of this variety of Cypripedium parviflorum on the Tongass NF. We located all four. At each site, we had multiple sets of eyes scanning every inch of ground for stems – for they are not only rare, but difficult to find. The first three sites were relatively abundant and some were in full flower, but the specimen we found at the fourth site was in poor shape. Reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea) reaching heights of four or five feet nearly covered the entire plant, and tree debris from a recent brushing procedure almost buried the few stems that were left.

The leaves were visibly chewed through and drooping. The chances of this fourth plant surviving seemed slim. I found myself questioning what to do. How do we choose to manage our forests? How do we decide to put our resources toward doing everything we can to attempt bringing this small cluster of stems to thrive again or acknowledge that we might not help this one, and to divert our work elsewhere? Conservation and land management is a complex task. It means making decisions about living beings other than yourself, while also managing for and understanding the impacts of your own species. It means taking the time to find the rare in the abundant, so that the ones not often spoken for might be.