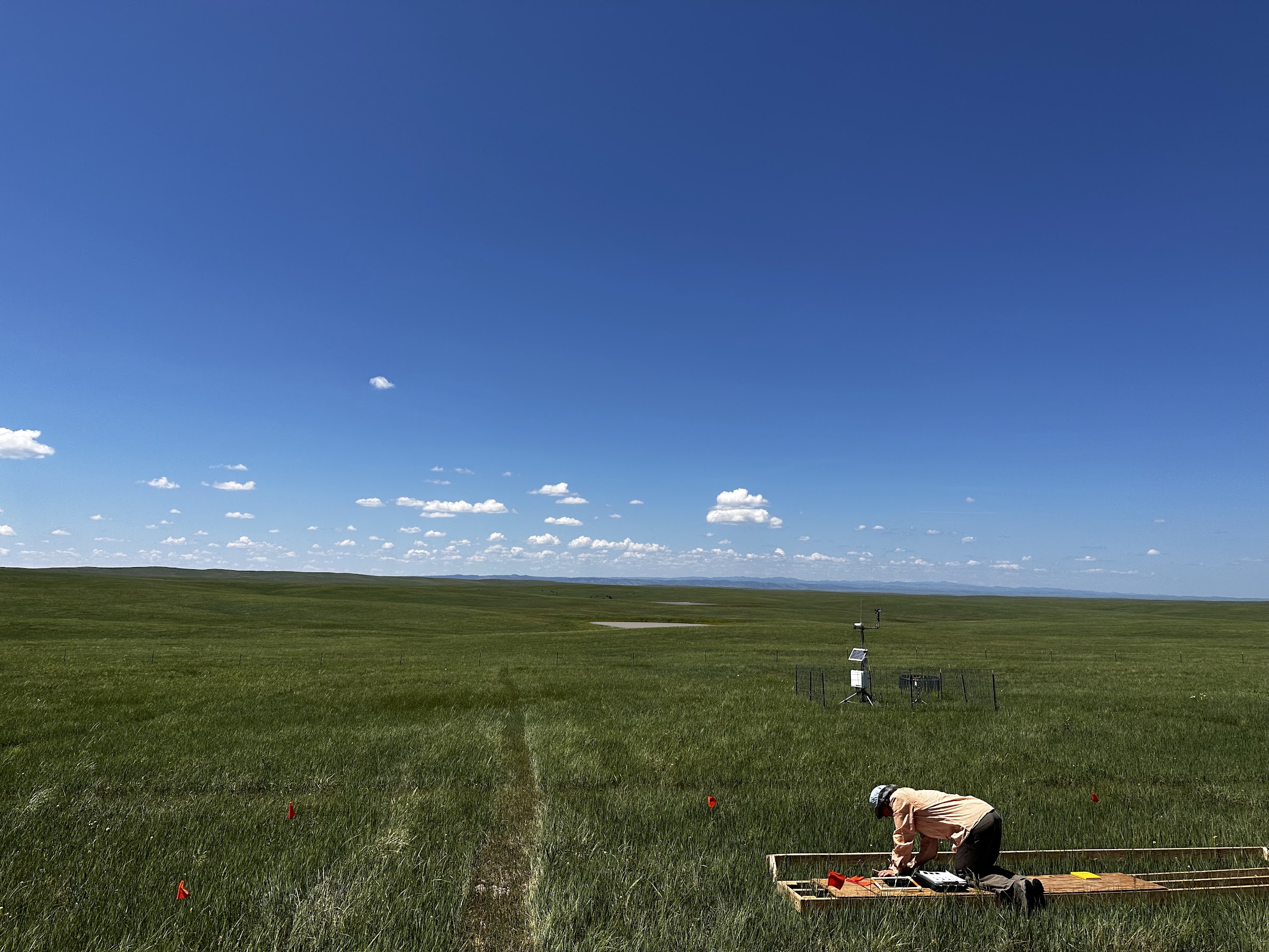

While the extent of our work for seed collections has been mapping potential population areas and scouting around the Caribou-Targhee, my co-intern Alex and I have been lucky enough to help out on a number of different projects, as well as spending a lot of time getting to know the plant populations here in Southeast Idaho. While working with a variety of resources across the forest, we have learned about riparian restoration, soil surveying, field photography, burn restoration, environmental education, and horsemanship. Every day is filled with opportunities to meet new people on the forest and pick up new skills.

One of my favorite projects we worked on had us in the field with the Palisades wildlife biologists doing goshawk surveys on various project areas in the forest. Goshawks are considered a sensitive species by the Forest Service, so any project that might alter the habitat needs to undergo monitoring to determine if there are any nesting individuals present in the area. After spending hours bushwhacking through the forest, surrounded by swarms of mosquitos, we were rewarded by seeing a male goshawk circling above us. When we returned to the area hours later, we once again spotted a male goshawk. Chris, the lead wildlife biologist, told us that this behavior likely indicates that there may have been a nest in the area. The next day, we went out to a different section of the forest to monitor a known nesting site of a female goshawk. Goshawks may build several nests in a given area and can return to the same nest year after year, so they had known of a few potential nesting sites that this hawk may have returned to, and earlier this season the wildlife crew had found the nest that she chose for the season. Joe, the wildlife biologist we worked with that day, told us how this hawk’s mate had been killed last summer at a local ski resort and that they weren’t sure if there would be any signs of reproductive activity at the nest because goshawks sometimes mate for life. After arriving to the nest site and settling down into the undergrowth to watch the nest, we noticed her eyeing us (I can say with certainty that I now understand the expression “watching like a hawk”). Goshawks are notoriously defensive of their nests, and I had heard from several coworkers that we should be on the lookout for divebombing birds- some even suggested sitting with a large stick on top of our heads to give the hawks something other than our scalps to aim for! Luckily, this female opted to keep a sharp eye on our group. After sitting in captivated silence for a while, we noticed motion underneath the female, and spotted the fuzzy white bodies of at least two chicks in the nest. Going out with the wildlife biologists was a really cool experience as it gave me a chance to understand a bit more about all the steps a project needs to go through before action can happen on the forest. Even though a management plan may be as simple as removing fuels from the forest floor, it can have serious unintended impacts on the sensitive species in the area and ultimately damage the ecology of the forest.

Another highlight of my time on the CT was helping out with a botany walk that my mentor set up for a group called Great Old Broads for Wilderness. During this botany walk, I got the chance to show off what I have been learning for the past month and help teach a group about plant identification and some of the native species present in the Teton Valley. The ladies that attended the walk were very enthusiastic and asked a lot of great questions about the plants in the area and some of the disturbances they were seeing along our hike. We got to tell them about the work we are doing for our seed collections, and they were very curious about what the point of seed collection was, the process of finding and collecting seed for various plants, and what they could do to help our project. I have worked in environmental education and outreach in the past, so it was fun to get to work with the public and educate a group about the work we are doing, especially because this group was so excited about learning new plants and exploring the forest with us.

While the first month has been filled with a ton of great experiences, it hasn’t come without its challenges. The first weeks of waiting for the field season to kick into gear definitely left me feeling a bit useless around the office, especially with the various difficulties I had in my Forest Service onboarding process. We have also faced many technical issues with Fieldnotes, making it difficult to document the work that we do with surveying for our target species. This, combined with our late start to surveying work, made it feel like we weren’t doing enough work for our seed collection project. Hopefully, as we move later into the season, we will be more able to make progress towards our seed collection goals!