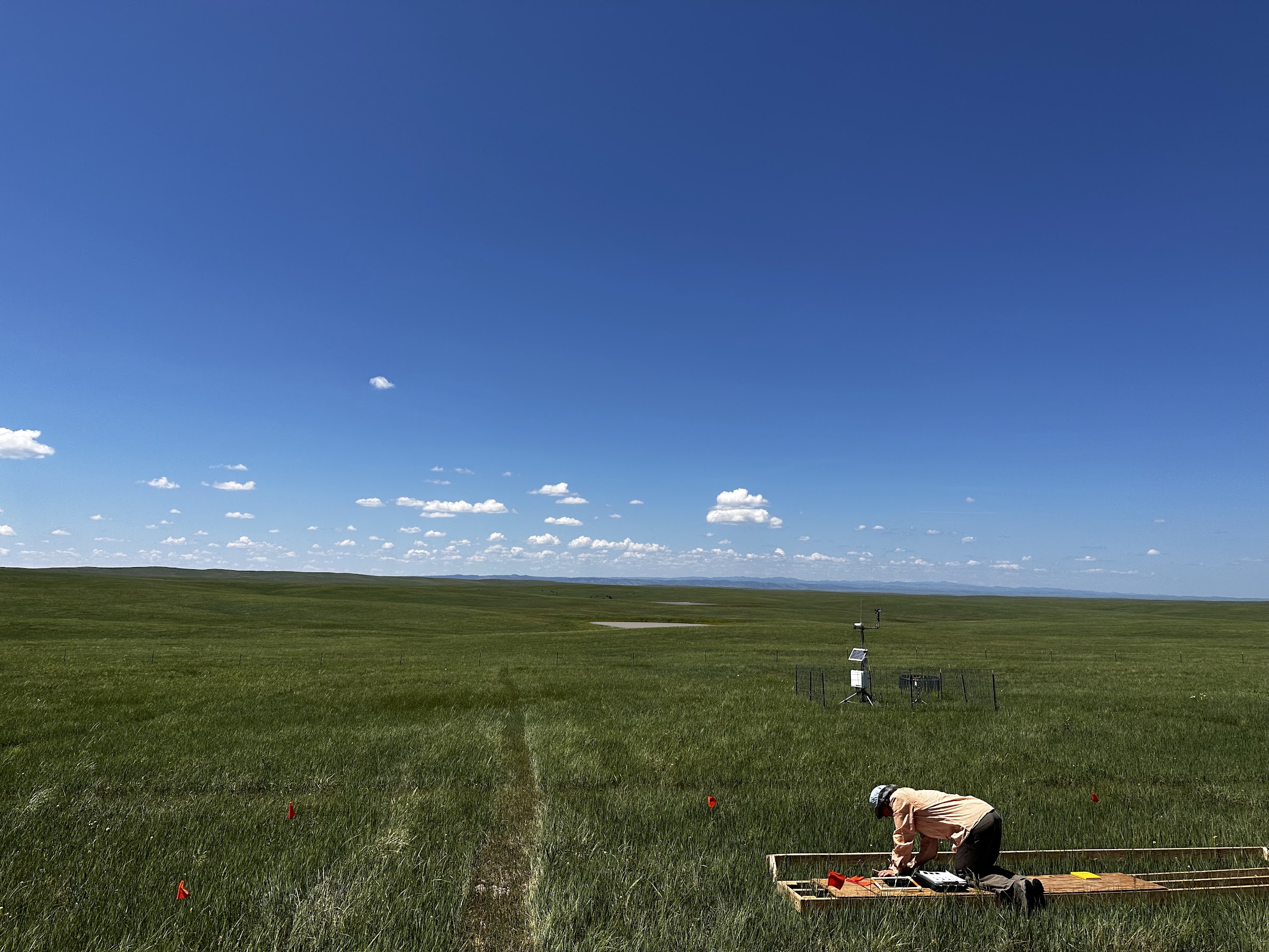

It has been a little over a month now since starting my work on the DRyiNG (Drought RecoverY In Northern Grasslands) project out here in South Dakota and I have already learned a ton about the mixed-grass prairie ecosystem of Buffalo Gap. I’m currently able to confidently identify over a dozen species found in the prairie, many of which are grasses that look nearly identical to each other.

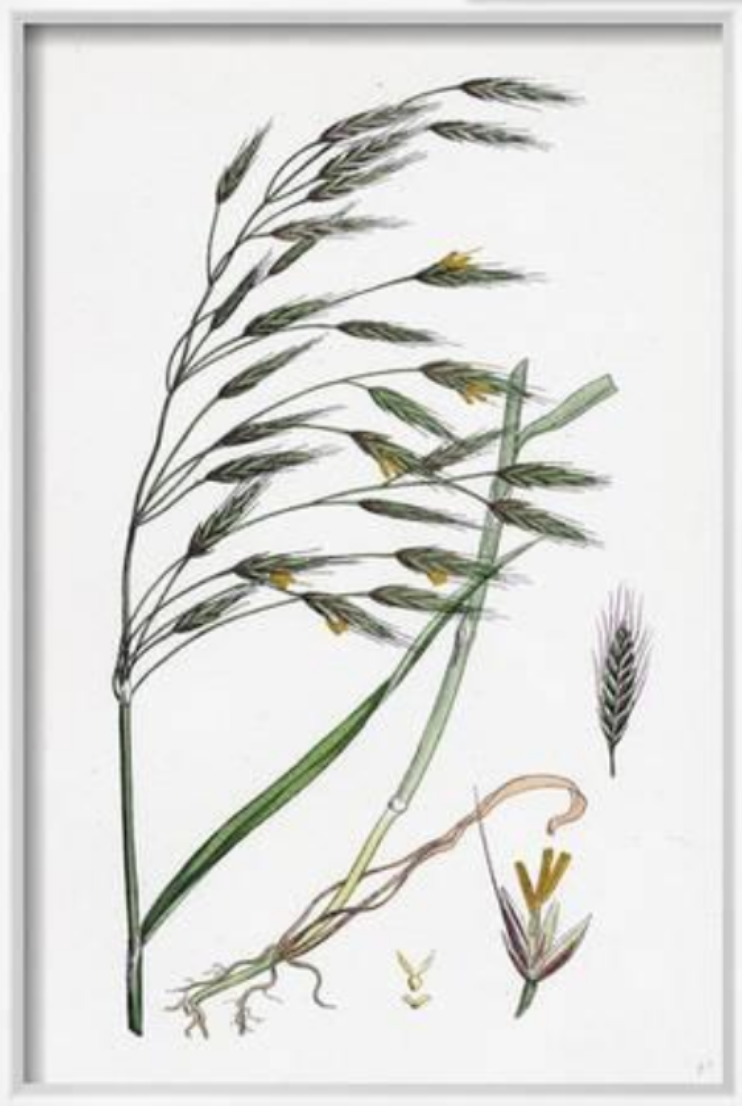

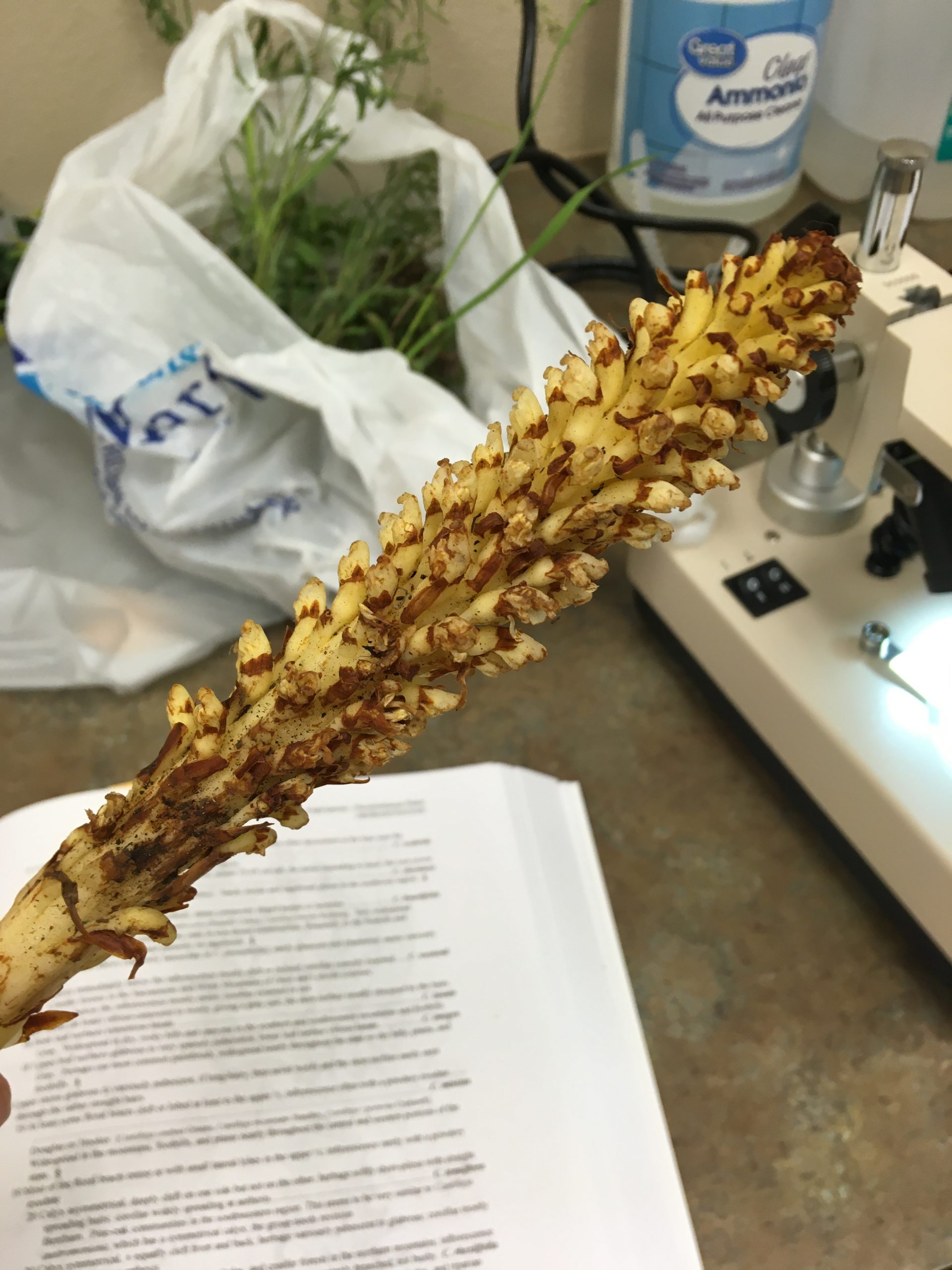

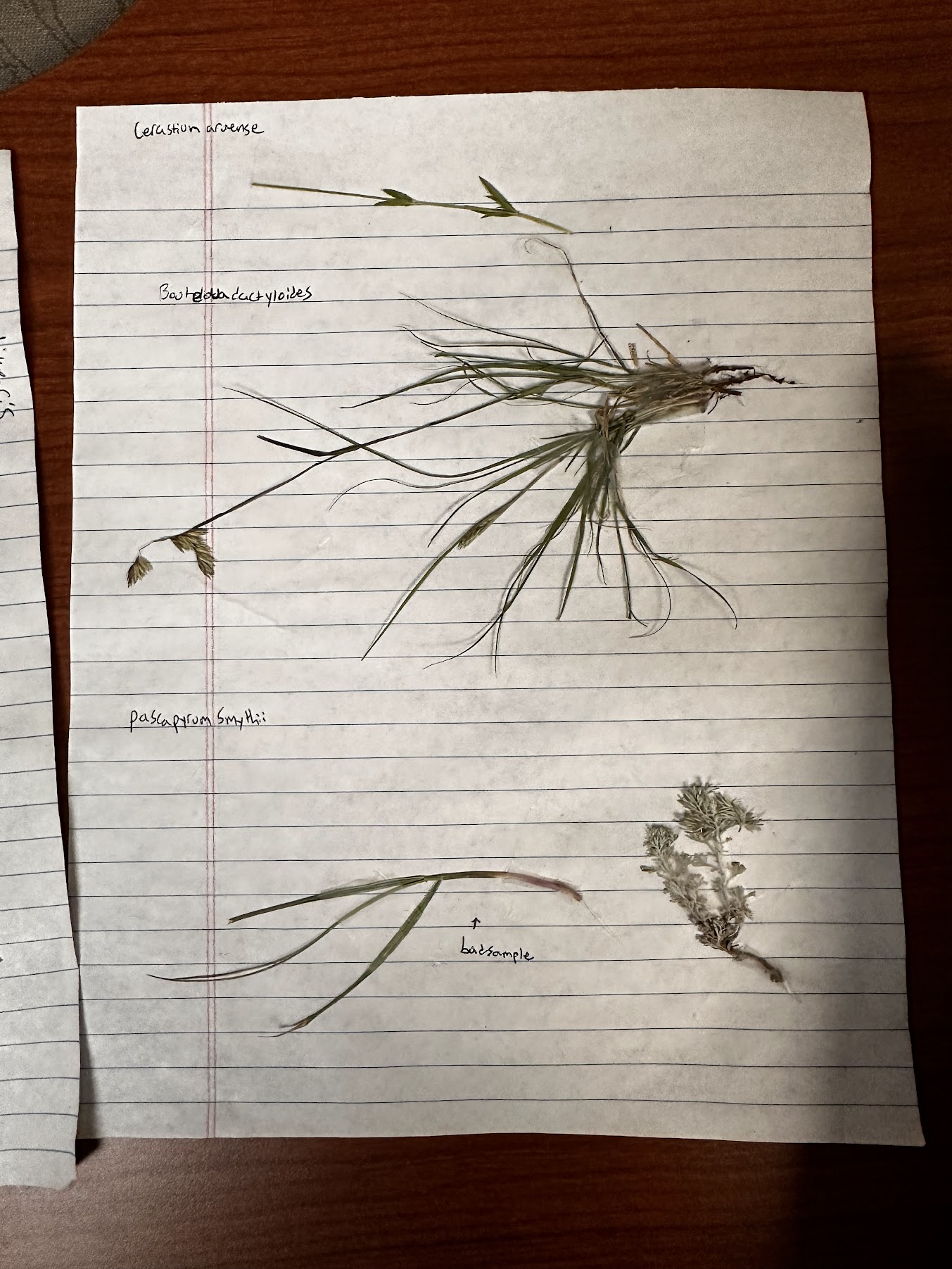

We spent the first week going over the defining characteristics of plant families we frequently come across and collecting some samples to enhance our visualization of some common species. Some grasses are easy to identify as they have very unique characteristics when compared to their neighbors. Pascapyrum smythii for example, is the most common grass we come across and it is easily identified by the purple coloration on its collar. Others are much harder like the three Bouteloua species we often encounter: B. curtipendula, B. dactyloides, and B. gracilis. These took me a while to get the hang of as they are all fairly simillar and usually only distinguishable by the location and quantity of hairs on the culm and leaves when not flowering.

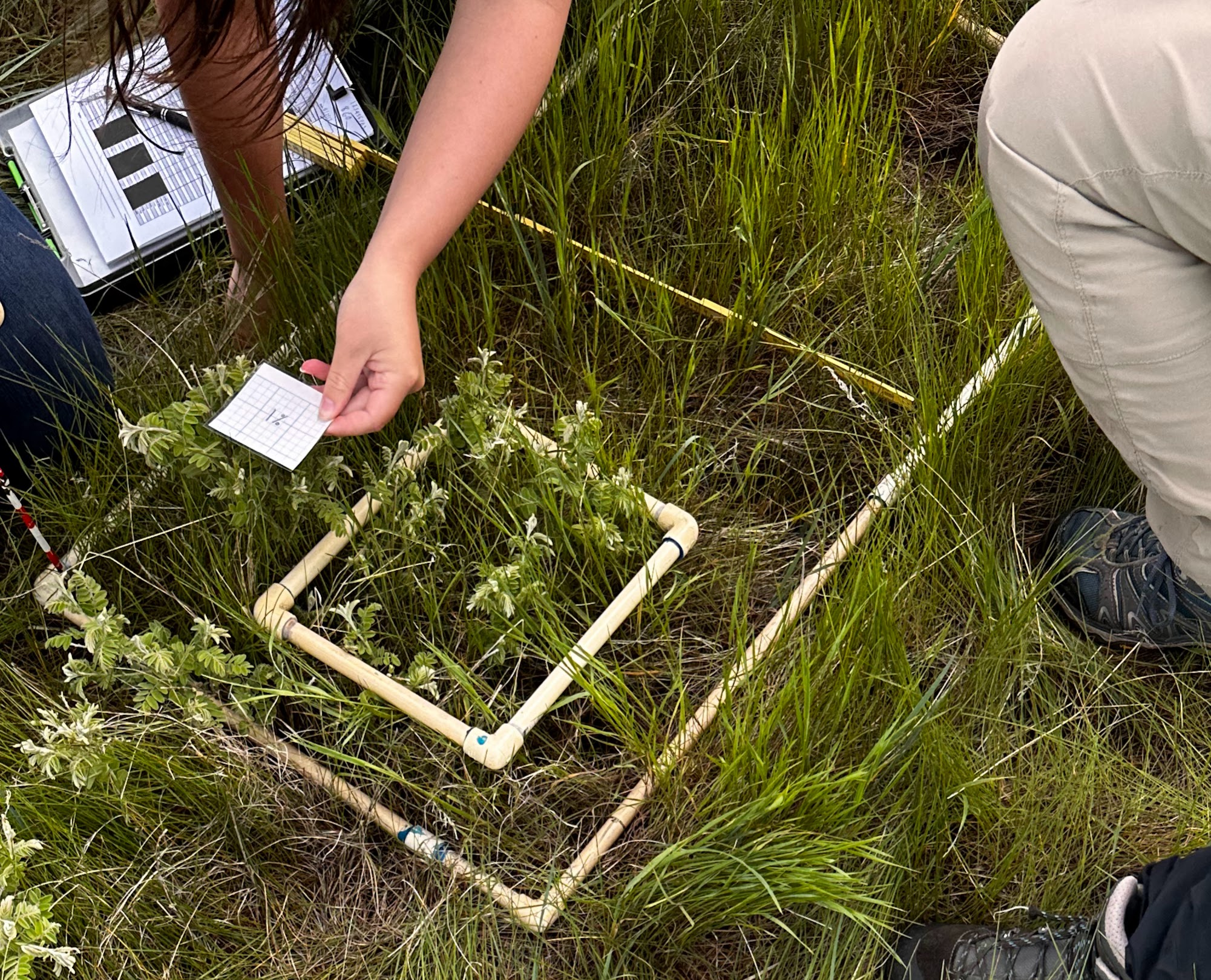

So far, our daily tasks have consisted of collecting aerial cover and stem count data within quadrats. This involves first identifying every species in the quadrat, estimating the area covered by each species when seen from above, and then counting the number of stems per species in a smaller quadrat.

So far, I have had a great time. Every day I learn new species and deepen my familiarity with those I already know well. I never imagined I would be able to go on a hike with my friends and not only annoy them by identifying all the cool flowers but all the grasses too! As the summer continues I am excited to continue my training as a grass wizard and learn more about other cool projects going on in the area.