There’s much to talk about here at the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Boise, ID! In the short two and a half months since I’ve began this position my partner and I have been darting all over the Great Basin involved in some cool research. Most of our time these days is dedicated to searching for a particular plant species, but we have also gotten involved in some smaller projects that needed extra hands.

Though first, I suppose I’d like to talk more about the Great Basin itself. Despite growing up in Colorado, and seeing parts of the greater Great Basin ecosystem, the basin isn’t something I have thought of very much. In fact, it took several hours of unbroken driving throughout this region to really appreciate its magnificent vastness, like a rolling sea of scrubland mottled with pinyon-juniper woodland in-between stark mountain ranges. Much like the sea, the magnitude of the apparently desolate land is intimidating, yet amazing.

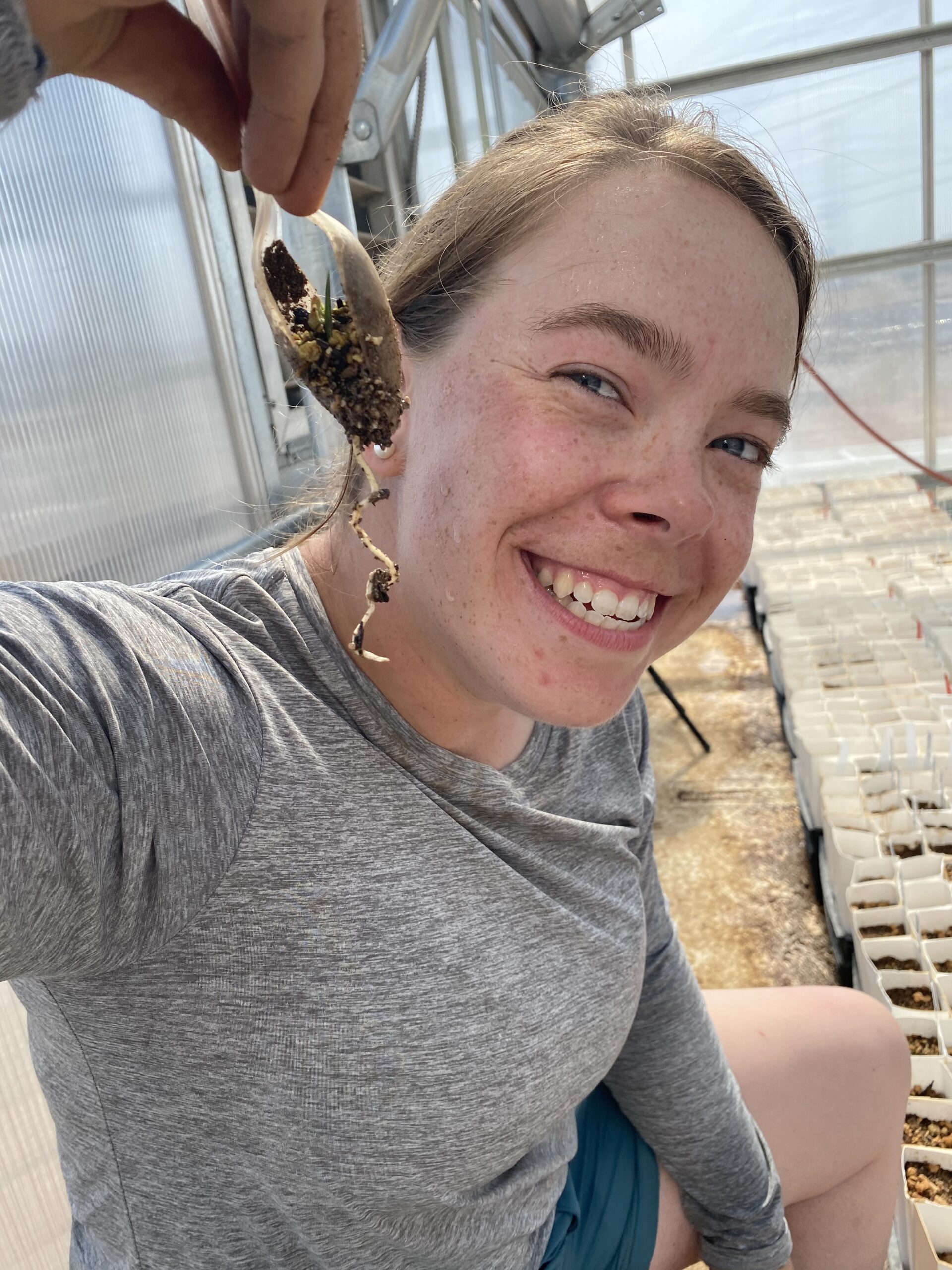

The Great Basin is defined primarily by the fact that the rivers flowing through this region do not drain into any major ocean or worldwide system. The water that enters the Great Basin, stays in the Great Basin (and now I know where Vegas ripped their slogan from!). This region is dominated by scrubland and pinion-juniper, but is home to a wonderful suite of forbs, one of which has been our primary focus for the past month, ERUM. ERUM stands for Eriogonum umbellatum, or sulphur buckwheat, a perennial from the family Polygonaceae. My field partner and I spend most of our time traveling to locations with presence records of this species, and collecting leaf tissue, herbarium vouchers, and seed from them when available.

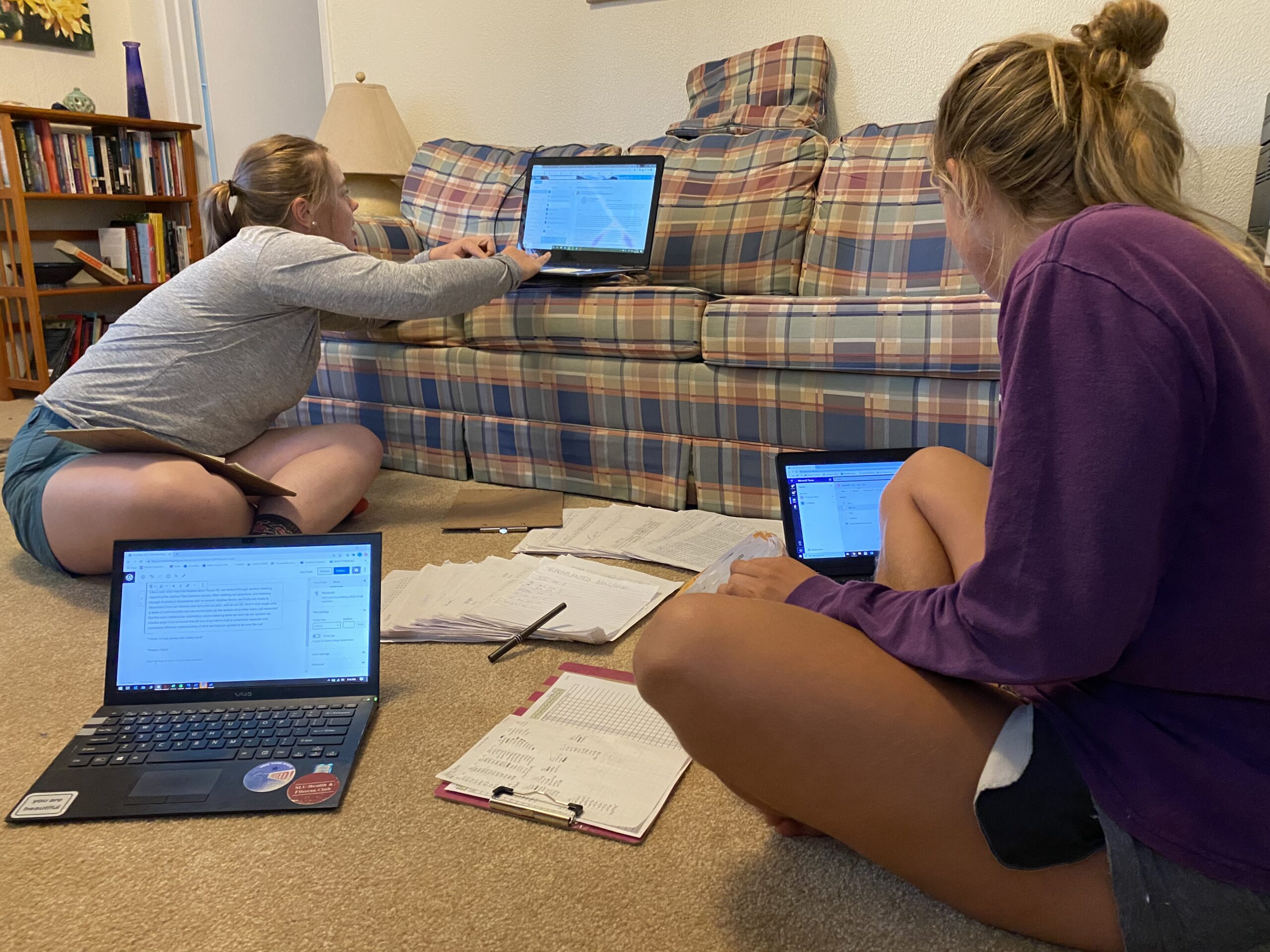

These materials are raw inputs into a research pipeline. Genetic material and phenological information are used to characterize varieties of this species while seeds from various climates are grown in several so-called “common gardens” across the Great Basin. All of this information gets united in an effort to identify “seed zones” for ERUM and its many varieties. These zones are areas throughout the Great Basin associated with particular environments and climatic conditions which result specialized in adaptations in ERUM. For instance, a sample of ERUM seed collected in a high-altitude forest meadow zone would likely not grow well in a low-elevation scrubland zone, and vice versa. So by identifying these seed zones, and characterizing the seed collections by said zones, restoration projects can use this information to select ERUM seed suited for the proper climate and environment. Developing large quantities of native seed is an extremely expensive process, and much seed can go to waste if the environment isn’t suitable. My mentor, Jessica, mentioned to us that after all the labor, permits, equipment, and resources, a bag of seed can be worth more than its weight in gold!

Hunting for ERUM feels like one great scavenger hunt, and it’s always a bit of a rush to stumble upon some. My time so far in this position has been pleasant. I feel very fortunate to travel to so many breathtaking places I likely never would have gone to otherwise. The great outdoors sure has a way of making one feel whole…

As we transition from traveling around the Great Basin collecting seed to setting up common gardens, I hope learn whether development of a reference genome is in the works, what sort of genes are being used as markers to identify varieties, as well as some general curiosities about the potential link between plant breeding, agronomy, and restoration.