A howling, cold wind forced the small crew of scientists to huddle closer. The group’s navigator glanced from her rudimentary compass to the horizon, concentrating her tired eyes on a small dark shape that stood opposed to the pale, starlit snowfields. The group was traveling in the Artic Circle, a land no more desolate now than most of the post-apocalyptic planet. At last, a man-made building resolved itself against the pale dawn. The tall concrete walls cut the wind and a quiet fell upon them. The navigator faced the stainless-steel entrance of the imposing tomb. She knew, though, that life lie frozen, preserved in that breathless place in the form of seeds. Millions of seeds, preserved by people of the past for the unknown future, contained the hope for replenished agriculture and revegetation. She had reached the ‘Doomsday Vault’ — the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

In the popular imagination, seed vaults conjure up post-apocalyptic visions of bunker-like warehouses filled with crop seeds for kickstarting a new human civilization. Helen Anne Curry, in her paper “The history of seed banking and the hazards of backup,” discusses the origin of this doomsday fear: a survival strategy for mid-20th century Cold War anxieties. The Cold War inspired a frenzy of record backups, computer and communication system redundancies, and other safeguards against global environmental catastrophes. Saving seeds represented an insurance policy for our food, forests, and the green of our planet. The Fort Collins Seed Bank in Fort Collins, Colorado fulfilled this need for redundancy, with the first “Fort Knox of the seed world’ opening in 1958 (Curry, 2022). The Svalbard Global Seed Bank, built almost 50 years later, continues to assuage similar fears but it also represents a more active, dynamic approach to modern day seed-saving needs. The Svalbard Seed Vault, located in the remote Artic Svalbard archipelago, functions quite literally as a seed “bank” in which a nation or organization deposits seeds in a safe box that is then available for withdrawal at the depositor’s request. Svalbard is a backup for the thousands of other seed banks throughout the world, a safeguard against the worst, but it is not a sealed off seed tomb. The seed vault regularly accepts deposits and honors withdrawals. To date, the only withdrawals have been from Syria in 2015 and 2017 due to the civil war disrupting a gene bank located in Tel Hadya, Syria (Dan, 2015).

Many organizations concerned with plant conservation and genetic diversity like botanical gardens, university laboratories, and nurseries, partake in some form of seed saving. The ability to preserve living plants, in the form of a seed, offers a highly adaptable opportunity for humanity to realize the needs and goals for both our local and global plant communities.

How It’s Made: Trees (and Plants) for Future Forests

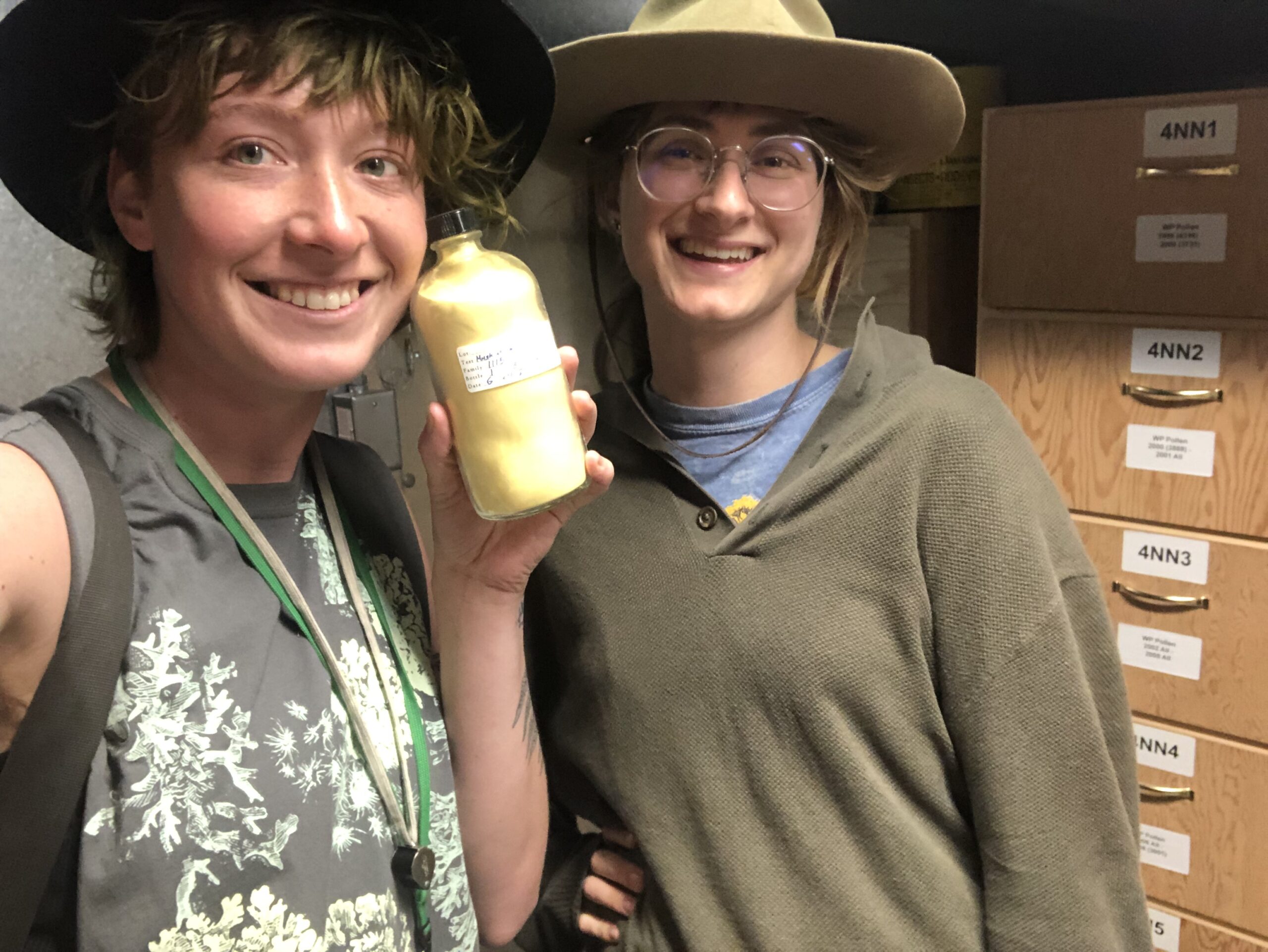

My co-intern and I visited the USDA Coeur d’Alene Seed Nursery in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho this month. The 220-acre nursery includes 25 greenhouses, 130 acres of bareroot seedbeds, multiple buildings for seed extraction, and numerous freezers for seed banking. The nursery provides native conifer, forb, and grass seedlings and seed mixes mainly for Region 1 National Forests in Idaho, Montana, and North Dakota (USDA Forest Service). The nursery participates in many projects including the Northern Region’s Tree Improvement program for growing and testing Whitebark pine seedlings for blister rust resistance. The forest I am working with, the Flathead NF, is sending seed to the nursery for extraction and use in grow outs to increase seed number of our target species. Eventually, the bulk-grown seed will form pollinator seed mixes for use back on the Flathead NF in disturbed areas.

We first toured the huge, industrially-sized “Seed Extractory”. Large boxes, each holding hundreds of pinecones, are stacked from floor to ceiling (see picture for scale). Hot air is pumped through the stacked boxes, turning the whole pinecone-filled column into a kiln. The heat opens the cones and releases the seeds. Inside the main building, ductwork lines then walls and ceiling, moving air from one machine to another, providing a means to separate the dense seed material from the chaff. Screens of different sizes could be fitted into the various sifting and sorting machines to accommodate a wide range of seed sizes. A sample from each batch of purified seed is then tested vias X-ray for seed viability. X-rays reveal dried-up embryos or hollow seeds that would otherwise escape notice. The nursery manager described the importance of creativity in purifying seeds and the lack of standardization in the seed cleaning processes since each species requires unique troubleshooting. Some seed extraction, despite all the helpful machinery, must be done by hand. This is the case for Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis). Whitebark pine is considered a “stone pine” due to the cone scales never opening, even when the seeds are ripe. Heating the cones up in the kilns only makes the scales close more tightly. The cones must be cracked open by hand, imitating the natural forces they encounter in the wild—being crunched by grizzly bear jaws or cracked by awl-like beaks of the Clark’s nutcracker (National Park Service).

We next moved to the storage room, which contained huge walk-in freezers that housed enough conifer seeds to meet revegetation goals for Region 1 Forests for the next 10 to 20 years! Conifer seed, like other “orthodox seed,” can withstand freezing and drying for long periods of time. Some samples of Lodgepole pine seeds stored at the nursery since the 1960s still have a 70% germination rate (Robertson, 2024). The freezers at the nursery are not as cold as the -18C of the permafrost-entombed Svalbard Global Seed Vault (Hopkin, 2008). Seeds stored at higher temperatures, a warmer -2C, are not destined for potentially century-long storage. Rather, these seeds are used for ongoing projects and near-future seed planting. Pollen and seed from white pine blister rust resistant conifers is stored in the freezers for the Northern Rocky Tree Improvement Project. Four defense mechanisms against the blister rust have been genetically isolated and some conifer species, represented in the freezer, contain all four mechanisms of resistance (Robertson, 2024). Seed banks, nurseries, vaults, and libraries provide the necessary storage space for reassurance that genetic diversity can be maintained for both short-term and long-term conservation goals.

Reimagined Visions: Keep Cool and Save Seeds

While the fear of global environmental catastrophe still informs certain aspects of seed banking, seed saving today serves many other interests and needs. The Millenium Seed Bank Partnership stores seeds from 13% of the world’s wild flowering plants, representing a concern for the ex-situ conservation of wild plants as opposed to seed banking of only economically or agriculturally useful plants (Lewis-Jones, 2019). USDA Seed Extractories and Nurseries like the one we visited in Coeur d’Alene increase the availability of native seeds adapted to local, native growing conditions (Kantor et al., 2023). Smaller seed banks, housed in non-profits or botanical gardens, provide localized seed collections of endemic or culturally and historically significant plants. Seed libraries provide an even more dynamic and accessible service in which people from the community can lend and share seed among themselves. Seed saving of any kind represents a “partnership” of the “the mobile species helping the immobile species” and, of course, vice versa (Lewis-Jones, 2019).

References

“Coeur d’Alene Nursery.” USDA Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/ipnf/about-forest/districts/?cid=stelprdb5085769. Accessed 30 August 2024.

“Whitebark pine.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/crla/learn/nature/whitebark-pine.htm. Accessed 1 September 2024.

Curry, H. A. (2022). The history of seed banking and the hazards of backup. Social Studies of Science, 52(5), 664-688. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127221106728

Dan, Charles. “Reclaiming Syria’s Seeds From An Icy Arctic Vault”. NPR, 24 September 2015, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/09/24/443053665/scientists-tap-seed-vault-to-rebuild-a-vital-collection-stranded-by-war. Accessed 30 August 2024.

Hopkin, M. Biodiversity: Frozen futures. Nature 452, 404–405 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/452404a

Kantor, S., Runyon, J., Glenny, W., Burkle, L., Salix, J., & DeLong, D. (2023). Of bees and blooms: A new scorecard for selecting pollinator-friendly plants in restoration. Science You Can Use Bulletin, Issue 58. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 11 p.

Lewis-Jones, K.E. (2019), “The First Step Is to Bring It Into Our Hands:” Wild Seed Conservation, the Stewardship of Species Survival, and Gardening the Anthropocene at the Millennium Seed Bank Partnership. Cult Agric Food Environ, 41: 107-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/cuag.12238

Robertson, Nathan. “Tour of the Coeur d’Alene Nursery”. Coeur d’Alene Nursery, Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. 20 August 2024.