During my time in the Umpqua, I have learned a lot about the nature of seed and seed collection. As something that I had never really given much thought to before, I have picked up on quite a few things regarding the matter. Though not extensive or something that can possibly be used across the board, I caught myself this last month making a mental rule book for the dos and don’ts of seed collection. Noting the things that nature had to teach me, I learned along the way what was easiest, the best, or sometimes the worst way to go about a process.

1. Never force seed. One thing that has stuck out to me the most, and should perhaps have been the most obvious idea, is that that seed will freely give itself to you when it is ready. It’s the whole purpose and the thing it wants to do the most – be released in its time of maturity. So when walking up to a plant, I now take note of how easily the seed gives itself up to me. Do I have to force it off of the plant? Or if I move too quick, accidentally bumping the plant, am I in trouble of losing my collection because it has sprung away at the smallest of encounters. If so, chances are I can pass go and collect my $200… after a trusty cut test of course.

// note – I wouldn’t necessarily think of berries and fruits in this way.

2. Following that thought, I move on to lesson number two: Be careful where you tread and grab. The number of times that I have lost the seed that I was reaching for simply because I moved too quick, missing what I was reaching for or accidentally bumped a plant with my leg… embarrassing. Springy seed pods, such as the Aquilegia formosa, will have you flying seed halfway across your work area with the smallest of movements. While not all seed is positioned for a great launching, those that are require patience and precise work – and maybe a little less shaking from drinking too much coffee in the morning.

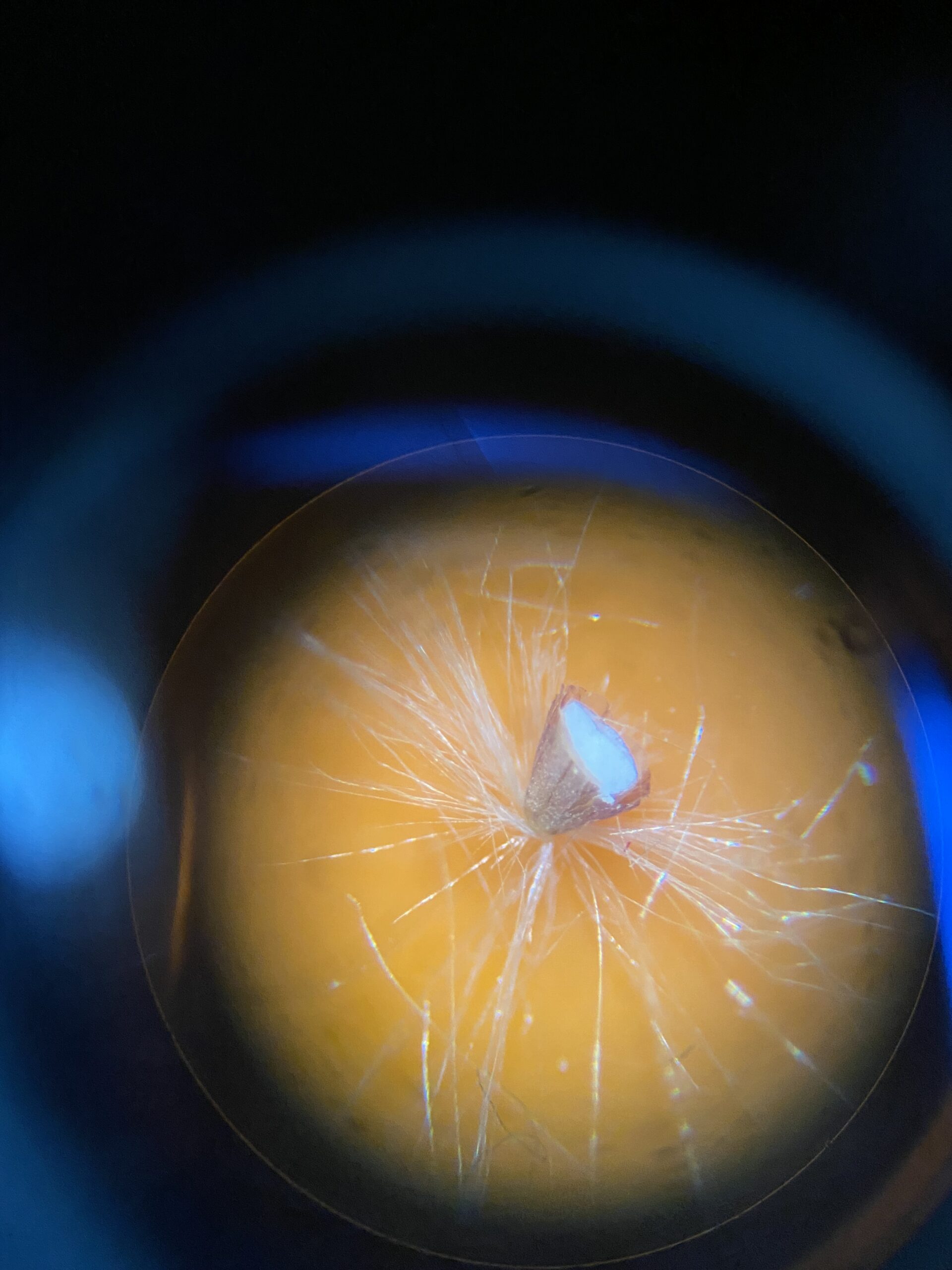

3. Avoid spiderwebs. Not necessarily a hill I’m willing to die on, but I can think of a few reasons to avoid spiderwebs. First, because of spiders, duh. The last thing I want to do is reach for a handful of material and have a spider or its web in my hand. Yuck. I don’t like it. I don’t want it. No thanks. Second, webs catch things. Mostly bugs, but sometimes other things too like seeds. Here in the Umpqua, one of our most treated non-native invasive species has a wispy seed comparable to that of a dandelion. There have been a few times that I have noticed these fluffy seeds caught in a spider’s web. For me, collecting spider webs full of other, perhaps unfriendly seeds is not worth it so I avoid it altogether.

4. South facing vs. north facing. Thanks to rocking climbing I knew that any rock, bluff, or thing facing south would be hotter than the north, and as a result, knew that any seed facing south would be ready for harvesting first (ignoring elevation). This is because the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, the south side of any object will see the most hours of sunlight in a day.

5. Work in designated lines. When working in groups, it is important to assign work areas within your collection site. I have found that working in transects works best. This allows for all areas to be covered. No accidentally missing plants. No double-picking. You are responsible for an area – you know where you began, you know where you stopped, you know how much you’ve collected.

Oregon Sunshine

Honorable Mentions

Don’t be greedy. Take your percentage, leave the rest, and trust that Nature will provide everything you are meant to take.

Don’t cry over spilled seed. Seed spilled in the wild isn’t really lost or wasted. It’s where it was originally meant to be.

Patient work, not speedy. Small collection species are tedious and require a lot of effort. Don’t give up on collecting early because it’s uncomfortable. Pay your dues. Take the time to do the work. Tomorrow’s collection species will probably be easier.

Walk around. Find the beginning or the end of a population to begin your work. Don’t start in the middle and make yourself all confused. Additionally, you might find something new that you missed before.

-Casey Mills