After the long drought the skies have sent rain down the night before and the morning is ready for the seed collecting day. The air hangs overhead like a mist, bringing a cool touch to your arm. You look overhead to the cloudless sky and sigh with anticipation as a gentle breeze hits the back of your neck. A shiver runs down your spine underneath your field clothes as you tuck your wool socks into your pants. Any attempt to stop the chiggers from finding your ankles is an attempt worth taking. You reach for your trusted wide brimmed hat, your ally in the war with the brutal sun, and slip on your long sleeved over-shirt. The gear is collected: a small pair of cutters, small white paper bags, a big leathery plastic bag, and water. Just enough to collect what is needed and no more. Working with mother nature instead of against her is our number one job today.

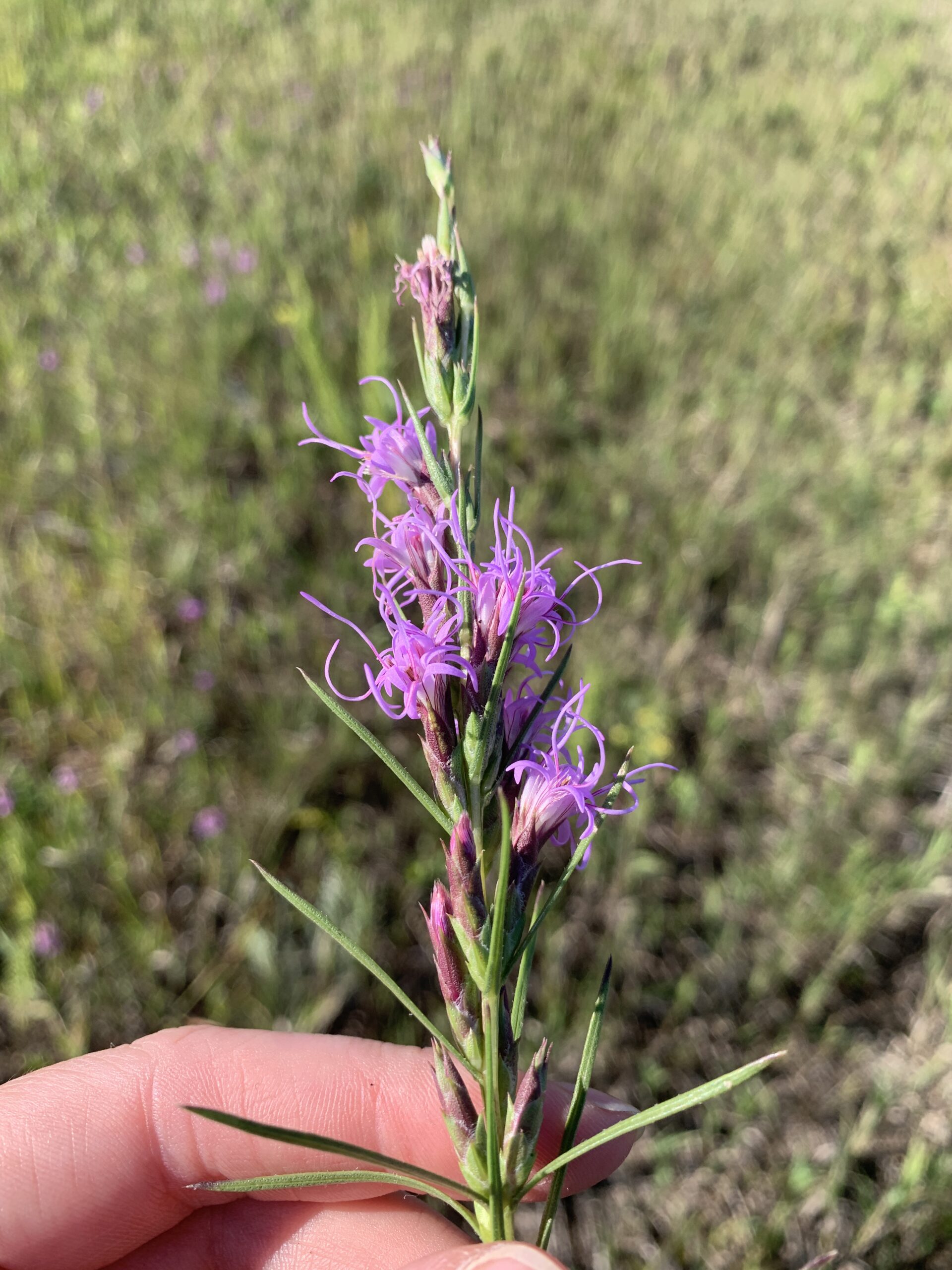

Looking over the prairie is different than the last time. The blooming purple of Monarda fistulosa has died down as she gets ready to go to seed and is instead muted by greens and reds. Still too early for the yellow sea to flood in yet we are in a holding period between seasons. The quiet month of August is upon us. But mother nature is still hard at work, you just have to know where to look to see her true beauty. She makes you work for it but these species are the most complex of all.

Bouteloua curtipendula is finally ready to collect as its deep purple seeds have now tanned to a pale brown. Close up the seeds are no bigger than the broken graphite piece of an extremely sharp wooden pencil. Yet far away the are much bigger. Hanging loosely on the small stem of the grama they are the easiest to spot in an upland prairie habitat. Outcompeting any of the bigger grasses in its way. The most exciting experience besides saying its name, is collecting the seeds.

My ”task” for this morning is to honor the ecosystem and take 20% of her Bouteloua seeds. This way it benefits us and still leaves enough to have another generation thrive. Luckily it is doing very well in this prairie. With one swift motion you place your hand on the stem below the seeds and pull upward until all of the seeds are in your hand. Pure satisfaction in one swoop.

You continue to walk through the prairie, now feeling the extend of the sun on your back as you pull another Bouteloua seedhead. Satisfaction. Making sure to step light around the wide Baptisa alba plant to more Bouteloua. Pull. Satisfaction. Spot some Amorpha canescens but its seeds arent wuite ready yet, so you make a mental note to come back in a week to collect that. Pull. Satisfaction. And you find a big clump of Bouteloua surrounded my smaller vegetation. Pull. Satisfaction. Pull. Pull. Pull. Satisfaction. You look down at the little plants around it, its light delicate whorled leaves around a tiny little stem. Bright white complex inflourescence among the top of some plants. You think you know what it is! But there is one more step you need to do to make sure. Plucking a single leaf from the stem you look closely at the leaf as a small bubble of white liquid starts to form on the end. Your guesses are correct, Whorled Milkweed has made its way to the prairie.

Asclepias verticillata is one of the smallest milkweeds at Midewin, but what it lacks in size it sure makes up for in numbers in a population! At some points its almost a field of milkweeds surrounded by other plants. The small stature can be overlooked by people looking for the more charismatic plants, but Asclepias can hold its own. It even goes up against monarch caterpillars and survived their munching to produce little seed pods. She is one tough cookie.

The sun is beating down now as the time nears to noon on the prairie. Your stomach starts to call out in hunger and you have drank almost all of your water source in your bottles. You check your bags for your haul, a lot of Bouteloua was taken, but while looking around there is so much more that is left. Success in your collection. We survey our hauls at the truck, each had been successful in their species seed collection. You look back at the prairie, the whispers of bugs in the background as the clear blue sky screams hello. Its peaceful being around so much life and knowing that you are not destroying. Its enchanting knowing you are helping restore more places to look just like this. It is inspiring seeing so many people around you care so much about this planet. It is the satisfying pull of the job.