2. Dalea purpurea ft. a visitor.

July kicked off with the most anticipated task of the field season: vegetation monitoring. Two and a half weeks filled with… Botany! Interns, technicians, volunteers, and specialists worked collaboratively to monitor four different tall grass prairie restorations. At each site, four 100 meter transects were established. Every four meters, a quadrat was randomly placed, and each plant within the quadrat was identified to species and recorded. That adds up to a total of 400 quadrats!

Groups of three would rotate roles, ensuring that there were always two identifiers and one recorder. The recording process was often quite intense; identifiers would continuously call out species like Sporobolus heterolepis, Heliopsis helianthoides, Oenothera pilosella… Meanwhile, the recorder would frantically scroll through the species list, occasionally selecting the wrong species and fall further and further behind. Nevertheless, identifying the plants presented the best opportunity for me to enhance my botanical knowledge and occasionally showcase my skills when I felt confident in my identifications. I relished every moment, from the plants to the people.

The data collected during these two weeks will help in estimating species richness and evenness, providing a deeper insight into the annual changes observed in restored prairies. While it was satisfying to successfully complete this project in a timely manner, I was sad that it ended so abruptly. I can only hope for the chance to participate in a similar project in the future.

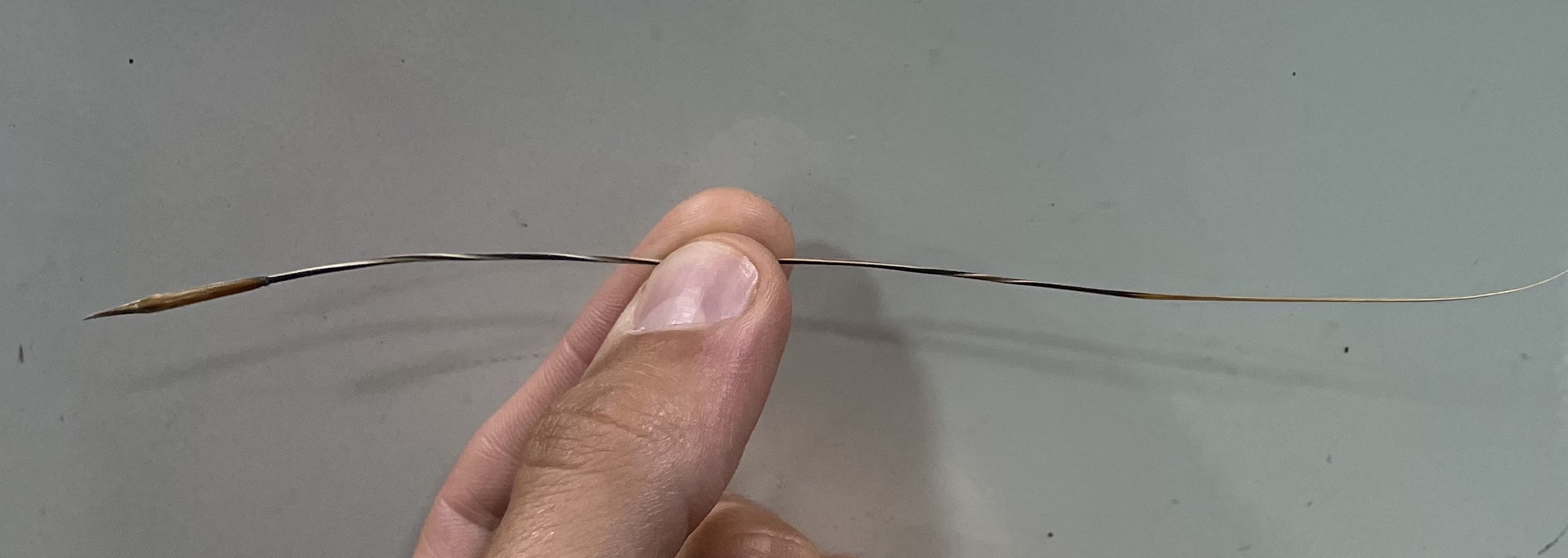

July brings a breathtaking display of colors and structure to the prairie. The towering inflorescences of Silphium laciniatum and Silphium terebinthinaceum, standing in some cases at an impressive 12 feet in height, inspire awe. Amidst this spectacle, the vibrant red flowers of Silene regia catch the eye from considerable distances. One species that never fails to excite me is Porcupine grass (Hesperostipa spartea) this species might have the longest awns of any grass in North America, reaching lengths of seven and a half inches. The seed, heavy and sharp, falls to the ground. The awns then “drill” the seed into the soil, twisting back and forth in response to changes in humidity. While the diversity here is undoubtedly remarkable, it is when you take a closer look that you truly begin to appreciate it. It feels like just yesterday the prairie was only knee-high now, it has transformed into an almost impenetrable thicket of forbs and grasses. I imagine it will go as quickly as it came, and before we know it, it will all start over again.

As our initial phase of seed collection draws to a close, the sedges are wrapping up for the season. Our attention shifts towards the genus Symphyotrichum, which takes center stage later in summer and extends through fall. Additionally, we look for members of the genus Sporobolus – a group of warm-season grasses. Amidst it all, my experience at Midewin has been incredibly fulfilling. The work itself is a joy, and the camaraderie amongst my fellow interns enhances the experience even more. A special shoutout to Dade, Veronica, and Harsha – you’re all truly amazing individuals.