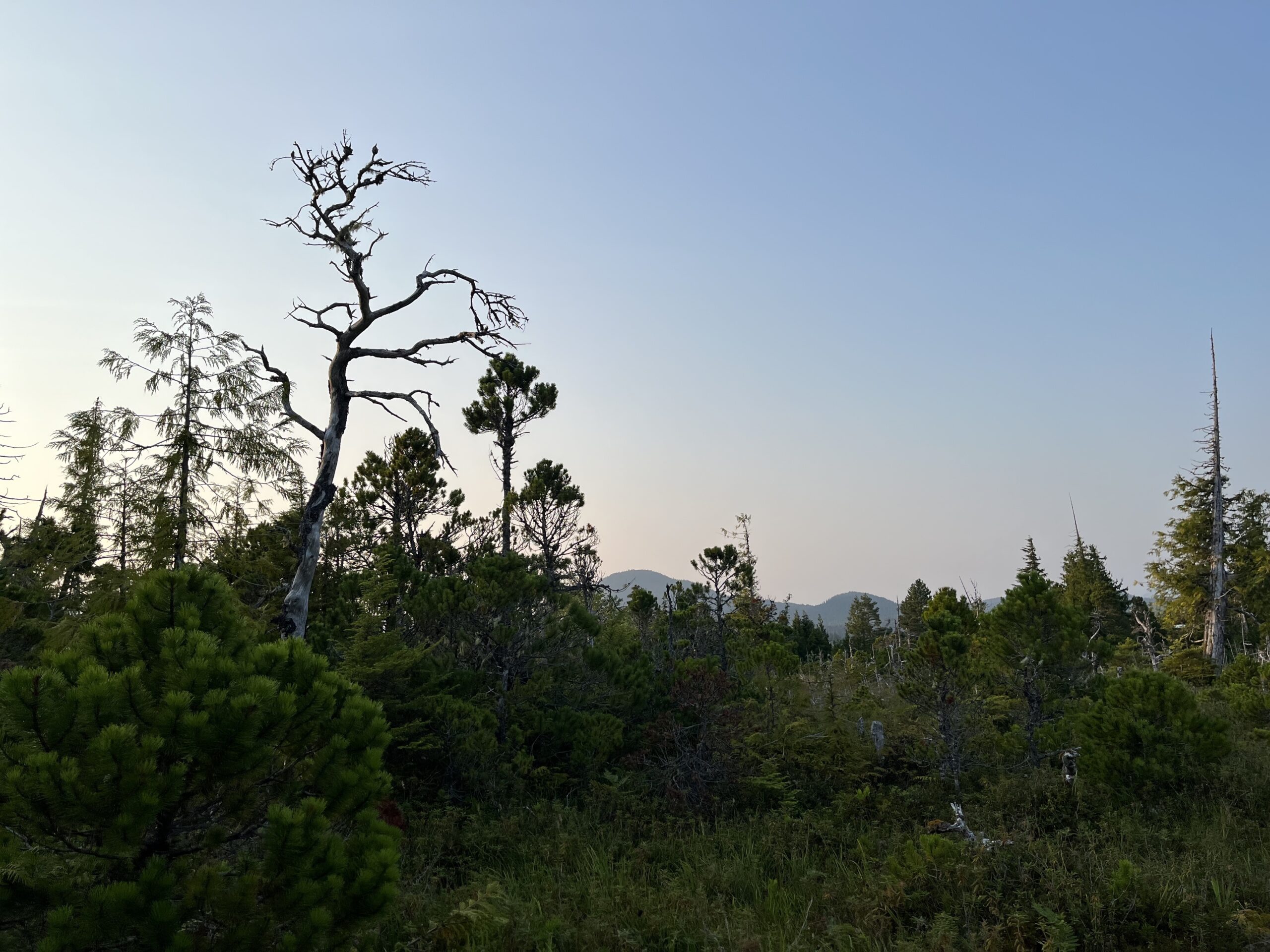

Lately, there has been quite a lot of change happening around here… With the switch from summer to fall brings the end of the season for some. And with the end of the season upon us, the tasks we are able to accomplish begin to shift as well. What is most striking is how quickly Montana seasons change from one to the next. We’re now experiencing quite the winter wonderland here in the Little Belt Mountains, and I am greatly anticipating the few field days we may have left and what we’ll be able to accomplish in a foot or so of snow.

My counterpart, Dayna, has left for the season. She was a huge help with many of the end of season tasks, and did what she could to make the end of the seed season easy on me in my final weeks. I’ll be here about a month longer than her seeing as I started about a month late. Work without a co-seed collector has been strange! But overall, it has been exciting to have the opportunity to work more with the wildlife crew. One of their members wrapped up and headed home shortly after Dayna did so. As she finished her final day, and left the office, Madeline, the only other seasonal wildlife technician quietly declared, “And then there were two.”

Dayna left just in time. With the wildlife crew’s help, we were able to make our last collection of Monarda fistulosa, or beebalm on her last day. It was such a beautiful and sunny day. So sunny, in fact, that the vegetation wasn’t even wet from the recent rains. We considered ourselves lucky as we split into teams of two and went off in separate directions. We collected all along these massive meadows that had some encroachment from the surrounding Douglas fir forests. It made me consider how large and sweeping these pocket meadows must have been before the days of no grazing and of active fire regimes… Regardless of encroachment, we were able to find and collect lots of MOFI, which was our final known location where there was collectable seed. Perfect timing as we were expecting snow the following week.

As an added bonus that week, I was able to join my supervisor, Victor Murphy, and what was left of our seasonal crew for a tour of the local Superfund Sites. For those reading who are not familiar with this term, Superfund Sites, at least as I understand them in this neck of the woods, are areas of environmental concern due to past mining activities. The sites we toured are just a 30-or-so minute drive down a dirt road from the Ranger Station. These sites are a large part of the reason for our seed collection efforts in this area, so it was incredibly interesting to hear all the where, what, why, when, and how of these sites. Apparently these sites have been polluting the watersheds and the land where people recreate (camp, swim, play) for around 60 years!! Tragically, there was signage put up about the issue just this year as liability for who’s technically responsible is arguable and somewhat unclear. By the end of that day, I had greatly exceeded my capacity for receiving information, however, I am still very grateful for the opportunity to know more about why our work here in the Little Belts is so critical to the restoration of these landscapes.

Snow did arrive the next week, however, it did not come as quick as projected. So the following Monday morning, I was prepared to get a start on office work, however, Victor asked if I’d be interested in joining the wildlife crew on a lynx habitat survey! But of course I wanted to join, and I was so glad for the opportunity. It is interesting to experience the forest landscapes through the lens of land management and wildlife habitat. We toured around parts of the Castle Mountains which has previously been areas where timber had been harvested. The idea behind the surveys is to see if the forest has since recovered enough to be suitable habitat for lynx. Sadly, we did not find many stands that would classify as such, and even the little we did find that classifies is not helpful to a lynx who travel one to five miles a day and require dense forest and tall/thick understory to move through… Being afforded these different opportunities as the seed work comes to an end has been a really awesome part of my time here on the Helena Lewis and Clark.

After only a couple days of Lynx Habitat Surveying, the snow came. For a Californian such as myself, this change has been rather drastic. I’ve only heard of and seen on TV what snow storms and white winters look like, but the actual experience of it is a bit baffling! Especially in the fall! It came, a foot or so of snow, overnight. We woke up and got to shoveling the walkways to the Ranger Station. We bundled up in layers, only to remove them as we worked. The temperatures hardly climbed above freezing the rest of the week. To think people live here year after year in this snowy/icy landscape. As I made my way to town after the storm had subsided, I couldn’t help but think, “Who in their right mind would live here and among all this dramatic weather?!” As somewhat of an answer to my own question, I do think the stunning flora in the summer does make it quite worth it. And after all, there really aren’t so many people out here comparatively, which is another perk in itself if you have an aversion to people.

Despite the low temperatures, the sun has been high in a blue blue sky most of the day. It does little to melt the snow, but it does feel good on the skin. The plowed roads are beginning to clear up, and I am curious to see what tasks I’ll be put on to do for the end of the season. Even with all the changes of late, I am still thoroughly enjoying my time spent here working on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forests.