Many of the mountainsides around the Lolo NF have turned to a shade of golden yellow as the larches turn and the weather towards the cold of winter. The Western Larch has become one of my new favorite trees, and I am so glad that I was able to watch this magnificent change of the seasons in such a beautiful place. It has been a successful season on the Lolo National Forest and although it is a bittersweet feeling to leave, I know I can leave this season behind feeling accomplished and full of new knowledge to take with me to my next destination.

Since seed collection is mostly complete, I have been able to spend some time helping out with different departments around the forest. The Botany/Weeds crew collaborated on a seed collection day for the hydrology department, collecting alder cones for a stream restoration project on a superfund site. We spent the day walking decommissioned roads where alder loves to grow, talking restoration and the joys of seed collecting. We also got to check out some completed restoration projects that the hydrology crew had worked on. It was cool to spend designated time exploring and appreciating interdepartmental restoration efforts. Another exciting part of the October agenda was being able to go out on a few days of work with the wildlife department. I was lucky enough to tag along with Luke, one of the wildlife techs on this forest. We did gate and barrier checks on roads that lead into modeled Grizzly habitat. While checking gates, we got to hike up to two different lookouts on the forest. I have become a lookout enthusiast, and hope to hike to many more next season.

The absolute highlight of October was my participation in the release of Northern Saw-whet Owls. The Owl Research Institute allows visitors to come and watch the process of owl banding once a week at the Flathead Lake Biological Station. I attended with a few co-workers, and we got to watch six owls get banded and measured for data. I even got to release an owl, which was a dream come true.

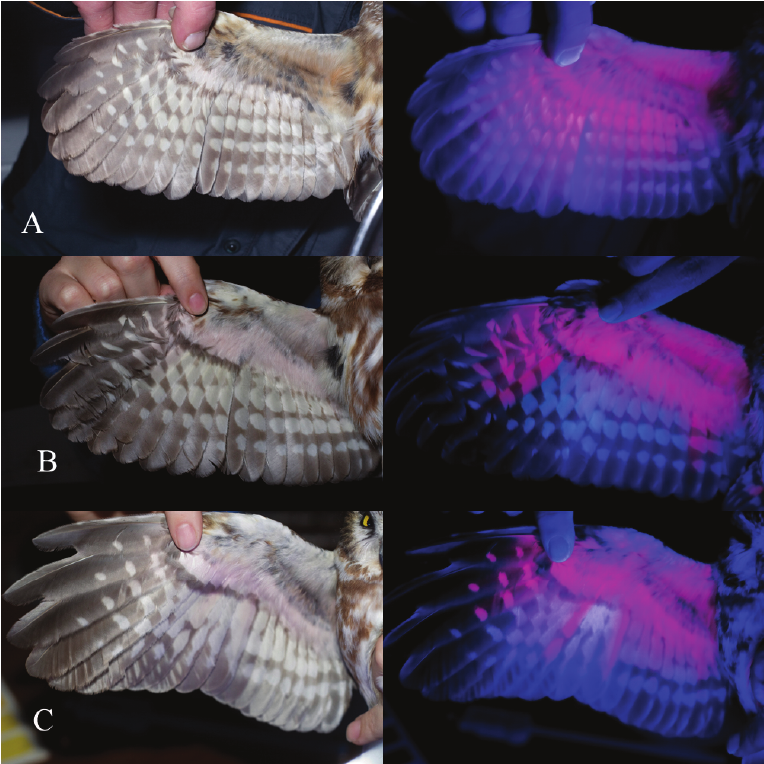

A little bit of information about these adorable owls: The Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) is one of the smallest owls in North America. They are known to nest in a large variety of wooded habitats, but prefer conifers with good cover. They hunt mostly small rodents and shrews, but have been know to prey on insects, songbirds and other small owl species during migration. They can be identified by their small size, round head, lack of ear tufts and bright yellow/orange eyes. A fun fact about these owls is that their age can be determined by a pattern on the under side of their wings. A UV light is shown onto the feathers and the pattern that appears correlates to the age of the bird.

Photo source: Weidensaul, Scott & Colvin, Bruce & Brinker, David & Huy, J.. (2011). Use of Ultraviolet Light as an Aid in Age Classification of Owls. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 123. 373-377. 10.1676/09-125.1.

Being a truly nocturnal owl, little was known about the migratory habits of these birds until around 1990 when project Owlnet was founded. This project includes more than 100 banding sites, capturing migrating owls and banding them for future ID. More information about these owls, the ORI and Owlnet project can be found here:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Saw-whet_Owl/overview

https://serc.si.edu/citizen-science/projects/project-owlnet-0

https://www.owlresearchinstitute.org/current-research-projects

Now there is snow on the ground here in the Missoula Valley, time to say goodbye to Western Montana and head back East!