Overnight, the Alleghenies transitioned from summer to early autumn. A breezy, warm, humid Sunday afternoon gave way to a morning of unmistakably crisp, cool weather: wool-sock-weather, wear-a-scarf-indoors-weather, light-your-woodstove-in-the-morning-weather. And you know what that means – seed collection season is well underway. As the humans here in Marlinton begin to layer up in cozy knit hats, windproof shells and bulky scarves, so too the plants shed their showy inflorescences in favor of cupule caps, seed coats, and follicle wraps.

I used to overlook seed season, which to me merely marked the period between the summer bloom and the delightful pigments revealed in autumn foliage. But this year is different. This year, my whole job revolves around finding, harvesting and processing wild seeds. Just today we harvested staghorn sumac, black elderberry, mountain ash, pokeweed and winterberry holly, while making notes on species verging on ripening next week: wild hydrangea, common milkweed, wild raisin. Instead of my standard indifference to the dried-up flower heads or inedible berries lining the mountain roads, I now find myself deeply entangled in a rotating wheel of fresh questions: which plants have gone to seed, and which fruits are ready to pick? What kind of fruit is this, and how can you get the seeds out? Does the seed grow easily when scattered on fertile soil, or does its hard outer layer require mechanical breakdown within the gizzard of a bird? The latter can be dealt with artificially (with scarification– no animals involved), but it certainly adds a few steps to the process. The propagation of wild seeds for ecological restoration work requires additional measures which the domesticated garden does not, but that’s the fun of it.

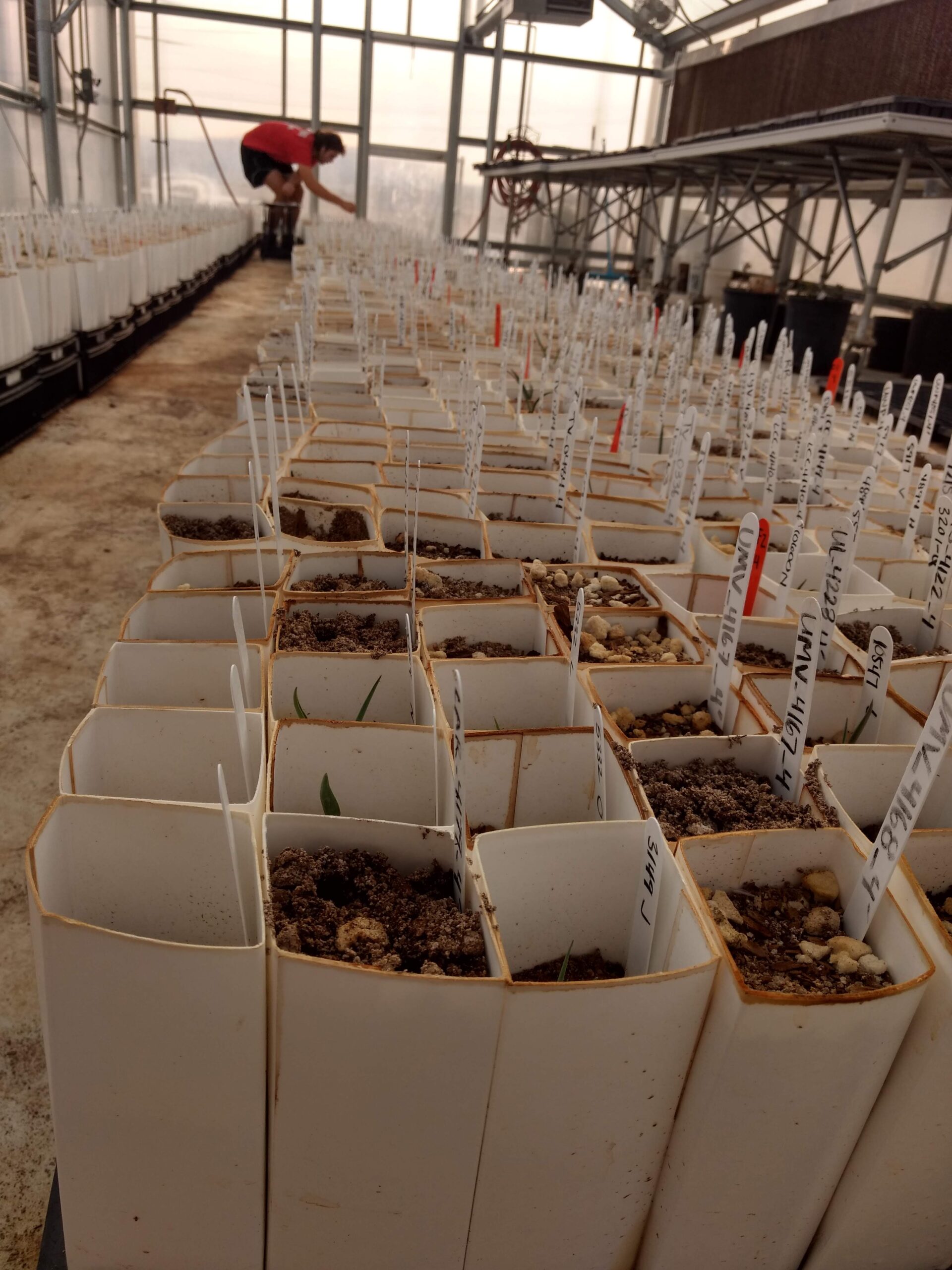

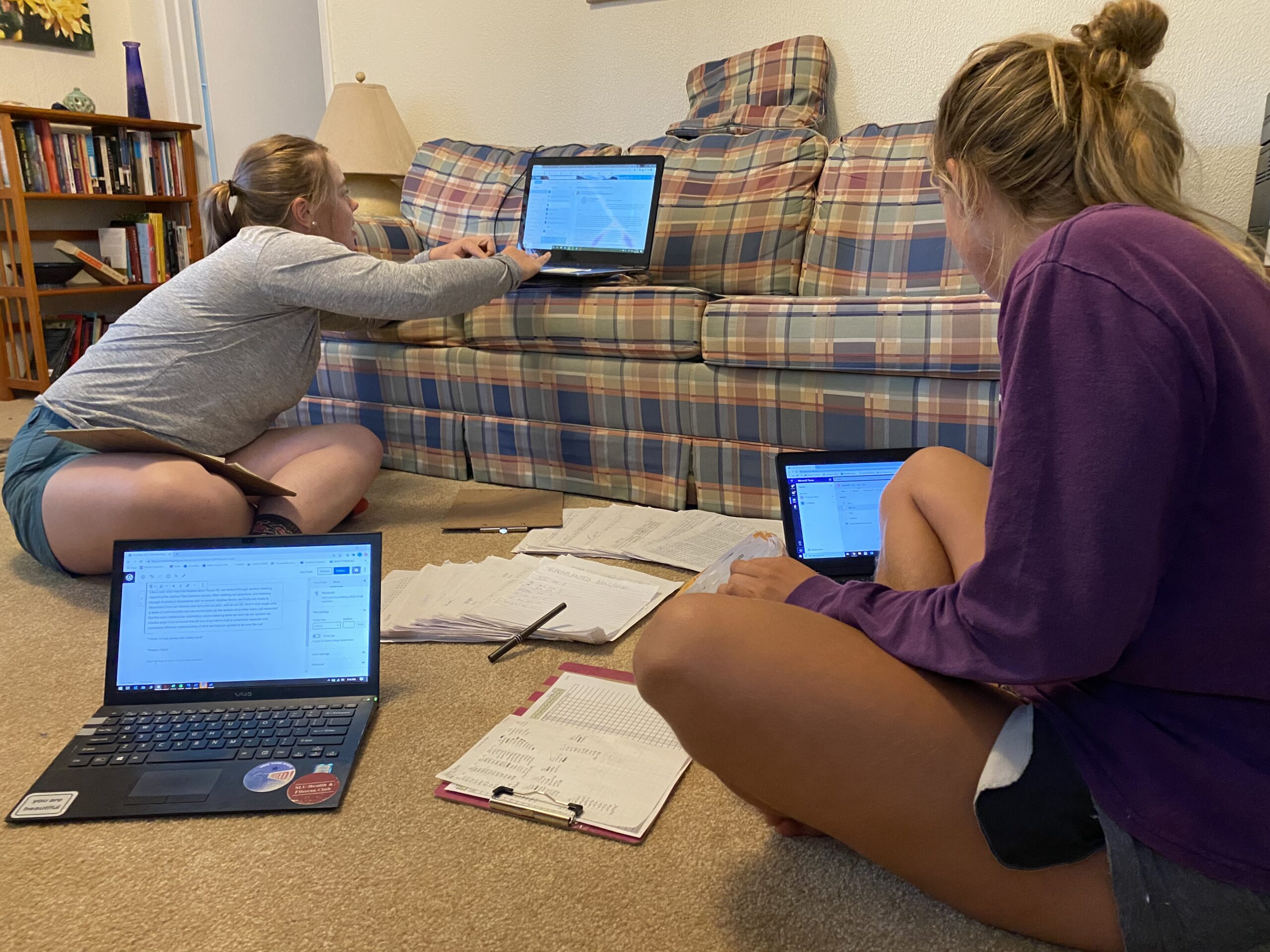

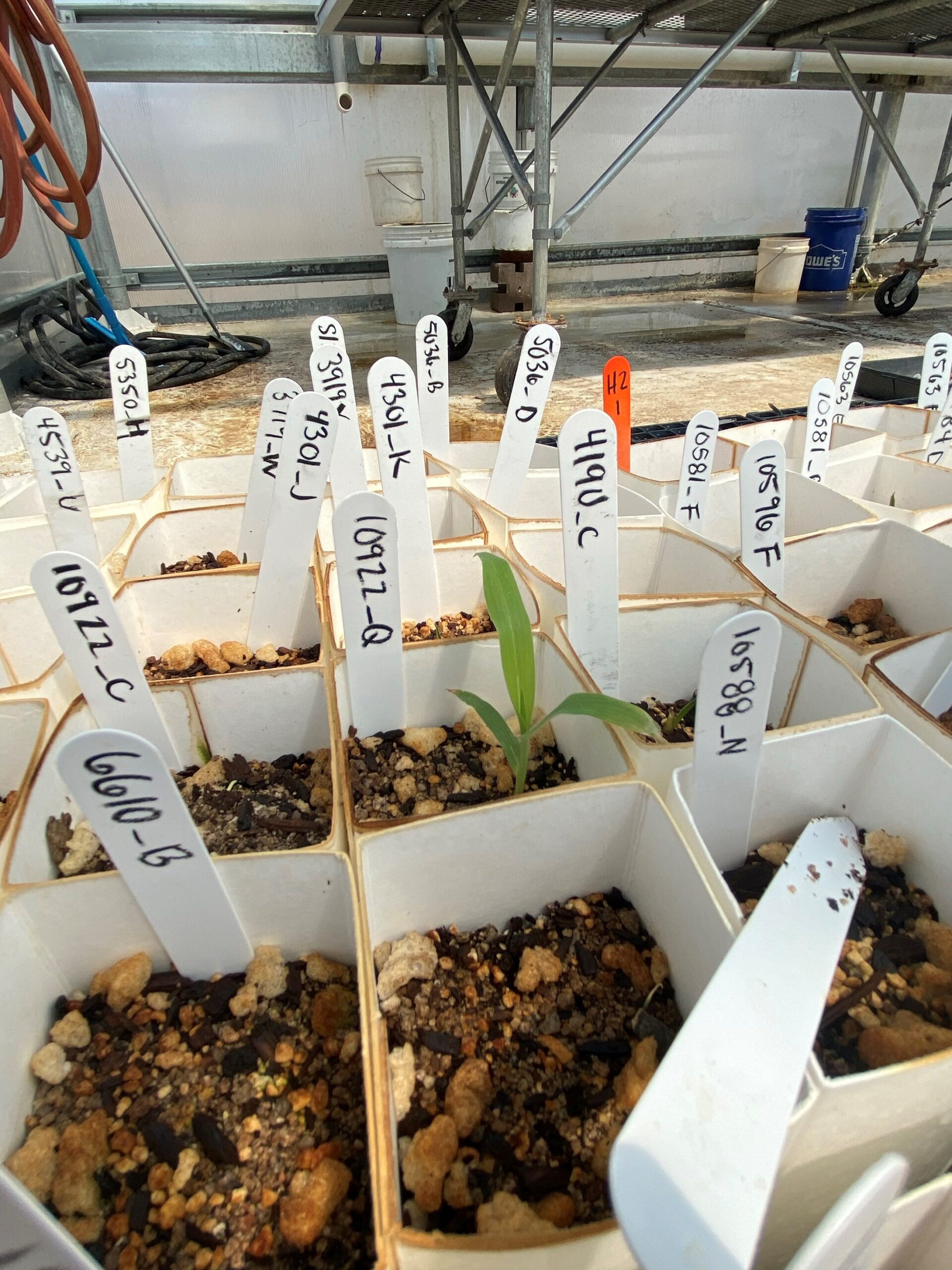

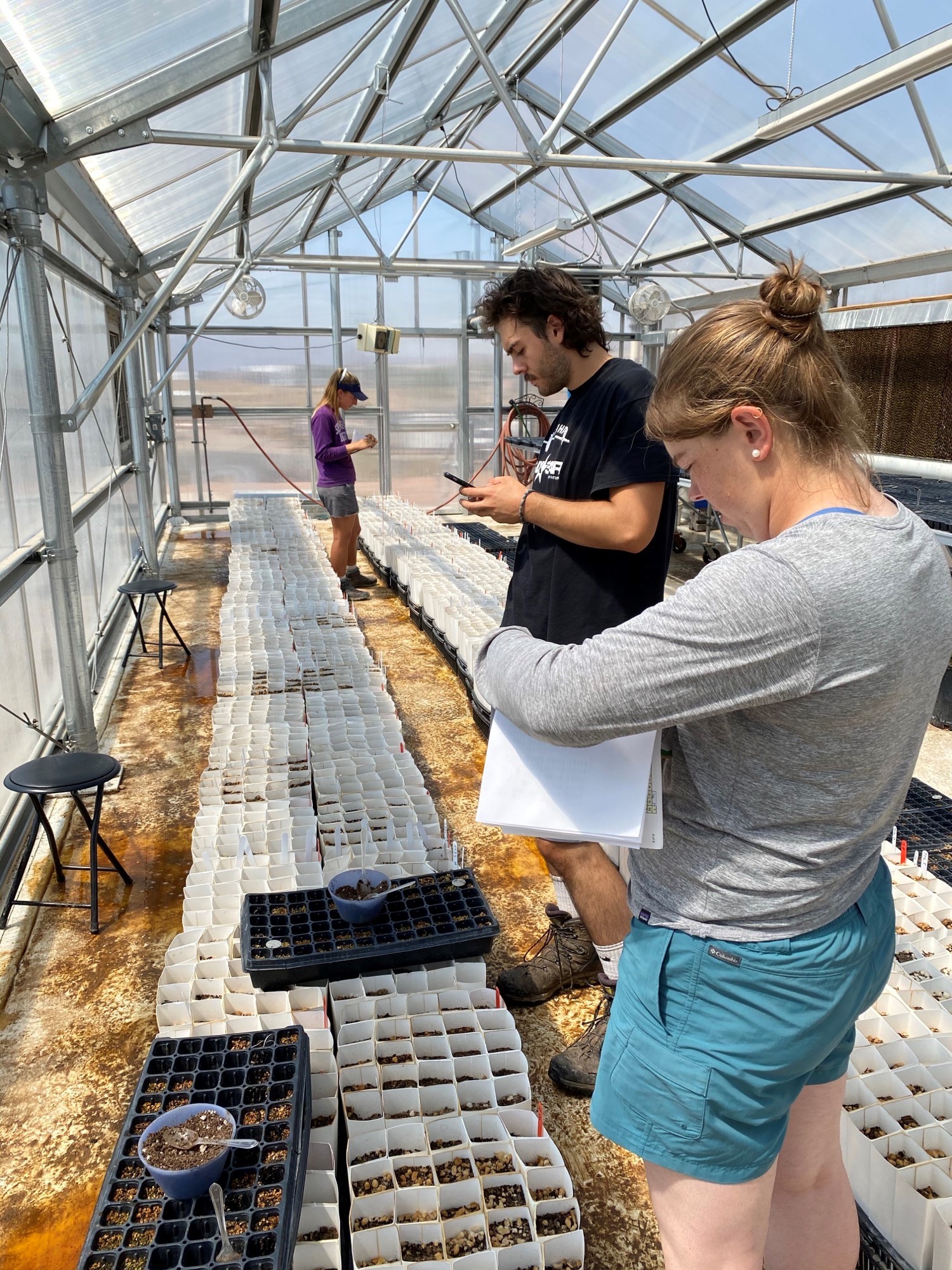

Our initial plans to work with a local nonprofit to process our collected seedstock have changed, and Ivy and I are embracing the challenge of doing it by ourselves. With the help of our supervisor, we are building our own seed cleaning station comprised of large buckets, trash bins, several gold pans of various sizes, and a few large tarps. With these tools, we will extract the seeds from the fruits we’ve collected, a process called “cleaning.” The cleaning process will involve de-awning and de-hulling any dry outer coverings and appendages, stomping on and shaking seeds loose from their fruit capsules, sifting seed contents through various screens, and winnowing away excess fluff using box fans and a tarp. By the end of the process, only the bare seeds will remain (theoretically). We will then bring these seeds to a local greenhouse where we will ready them for propagation and seed mixes. Soon enough, our wild seed mixes and propagated plants will be used to restore native red spruce forest to one of the reclaimed mining sites in our ranger district.

But for now, we will spend the rest of September and October focusing entirely on collection, dying our thumbs magenta with pokeweed berries, clipping off staghorn sumac and checking milkweed follicles for ruptured sutures. The collected seed will be stored in our seed cooler seed season is over, the autumn leaves have fallen, and it’s time to begin the cleaning process. Until next month!