A quick introduction: Hi! My name is Lili Benitez (she/her) and I am interning with the Owyhee Field Office of the Bureau of Land Management office in Marsing, ID. I am a recent graduate from New College of Florida with a degree in Environmental Studies and Spanish, with a focus on plant conservation.

Just a heads up- in this post I’m going to be mentioning /discussing stolen land, police violence, and racism.

I want to start this post acknowledging that I am writing and working as an uninvited visitor on the unceded territory of the Shoshone-Bannock and of the Paiute tribes. This is important to recognize especially in relation to the Bureau of Land Management, an entity created as a result of colonization and the removal of native people from their land. By 1866 the Boise River valley and most of Southwest Idaho was taken from these tribes by the United States government. To control the newly acquired lands, The General Land Office (GLO) was created in 1868, which then merged into the Bureau of Land Management in 1946. As an intern, it is vital for me to understand this dark history and learn about the indigenous communities impacted.

In the wake of recent attention to murders of Black people by the US police force and the following protests over the past months for Black lives, many environmental and ecological organizations continue to stay silent or make performative statements of solidarity without meaningful action. When the history of this violence is so intertwined with the racist history of white environmentalism and land management, it is unacceptable for these organizations to not speak out. We can’t be advocating for plant conservation without also fighting for justice for Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC), LGBTQ+, disabled, and immigrant communities. As a white, cis, Latinx woman, I walk through this world and into these environmentalist spaces with certain privileges. While I am by no means an expert on social justice issues, I hope to practice allyship for these communities. In addition to marching, donating, listening to and amplifying BIPOC voices, one of the roots of this process is unlearning years of biased education and confronting the racist histories within my area of study.

I’d like to share something I learned last month from listening to the Dope Labs podcast episode “Skin Deep”, and reading Ibram Kendi’s book, How to Be an Antiracist. As a young biologist, I learned about Carl Linnaeus, the “Father of Taxonomy,” a famous naturalist and botanist. However, what I never learned was that he was the father of biological racism as well. Kendi draws attention to the insidious nature of taxonomy at its invention, demonstrating how Linnaeus, in 1735, was the first to color code the human races as White, Yellow, Red, and Black in Systema Naturae. Kendi points to this moment as the start of the “blueprint that nearly every enlightened race maker followed, and that race makers still follow today… racist power[s] created them for a purpose (p. 41).” Like so many other white men that tend to be idolized in the environmental field (the National Park Service still has sites named after John Muir and other racist idols), Linnaeus was a white supremacist, and his taxonomic ideology still influences how we talk about race today. What does it mean for us as botanists and biologists to hold so much faith and respect for this system of classification when this is its history? How can we actively work to confront racism and colonial thought within our fields on a daily basis? Stay tuned for a more lengthy post on colonial influences in botany.

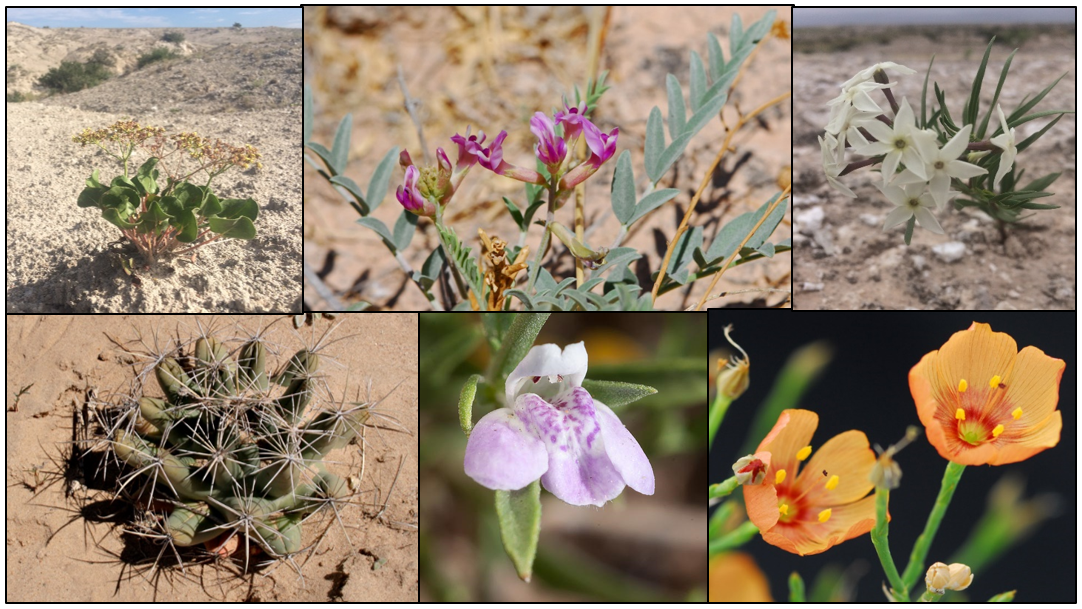

Just as I am learning about these connections between social justice and my work, I am also connecting with the local environment in the field. It is amazing to have the opportunity to be outside and hang out with plants all week. This month I’ve been getting acquainted with the sage grouse habitat in the area, and learning about these plant communities. As a Texas local, everything here is new to me, which I greatly appreciate. I am learning Assessment, Inventory, and Monitoring (AIM) techniques that examine species diversity, plant composition, and soil quality, mostly for range management. However, my favorite days are those where we conduct rare plant monitoring. On these days, I go out with my mentor, Jessa, to try to find cute rare plants and evaluate how they are doing.

To close out, I’d be remiss if I failed to mention it was Black Botanist Week last month. This effort was started by Bucknell University post-doctoral researcher Tanisha Williams and others as “a celebration of Black people who love plants. This plant love manifests in many ways ranging from tropical field ecologist to plant geneticist, from horticulturalist to botanical illustrator. We embrace the multiple ways that Black people engage with and appreciate the global diversity of plant life.” Along with Black Birders Week, these celebrations of Black scientists are a great example of combating Anti-Black racism in our fields and can inspire young BIPOC scholars to see themselves pursuing these careers. Go check out the hashtag #Blackbotanistsweek on Instagram and their website for more info.

For more information about the Black Lives Matter movement in my part of the country, check out the BLM Boise website and follow them on Instagram and Twitter (@blmboise). Additionally, to support local Indigenous efforts, check out the Nimiipuu land protectors, whose community and sacred sites were being threatened by the “Rainbow Family Gathering” this past month as an influx of tourists and outsiders arrived in Riggings, ID. Find them on Instagram (@nimiipuulandprotectors) to learn more and support their work.

Until next time!!

Lili