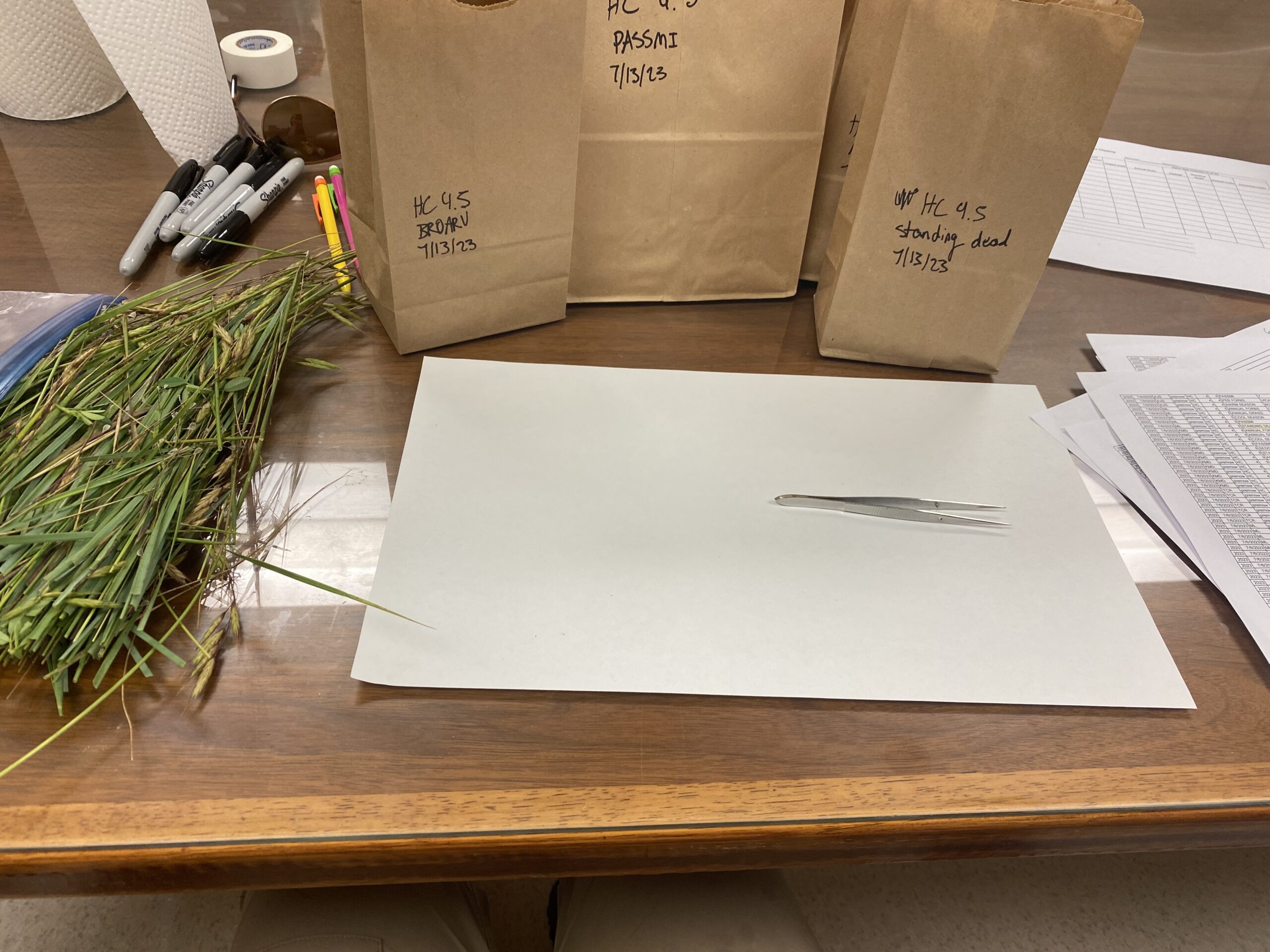

We’ve made 15 native seed collections, traveled through 5 states, and had countless exciting, educational, and inspiring days on the job. Here are some highlights!

Calumet Region Park Tour

Our crew tagged along with the Stewardship and Ecology of Natural Areas crew for a tour of Chicago Park District restorations/re-creations on the South East side (Calumet area) of Chicago. They’re attempting a project at Big Marsh Park unlike anything I’ve ever seen. They’re restoring wetland habitat and capping an old dumping site- a super unique problem to solve, especially with little to no budget. If you’re in the Chicago area and like to mountain bike, the bike park at Big Marsh is a must. You can rent bikes and thereby support the habitat restoration efforts with your money and enthusiasm. I didn’t take any photos of the bike features because I was too busy flying around on my bike with childlike fervor.

Neighborhood Natives

Finding native plants in the dense urban environment of Chicago never fails to be heart warming. Most of Cook County is developed and densely populated and concrete covered.

Before this job, I was not at all passionate about landscaping. Oh, how things change.

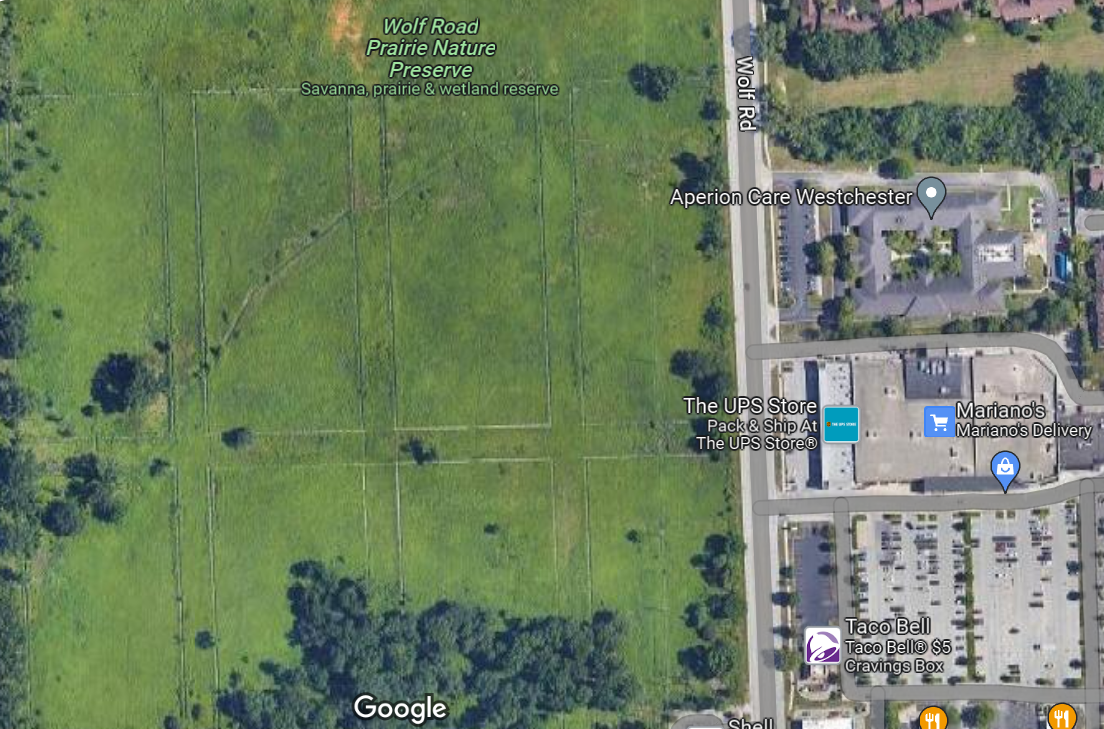

Cook County, IL is also home to one of the oldest and largest forest preserve districts in the country. A Resource Program Manager of Forest Preserves of Cook County led a day of “Reading the Landscape” which included a trip to a unique Illinois Nature Preserve called Wolf Road Prairie. The southern portion of Wolf Road Prairie is crisscrossed with sidewalks—laid for a planned subdivision ended by the Great Depression. The concrete strips throughout the rare remnant black soil prairie are disorienting and thought-provoking.

My First Trip to the Upper Peninsula

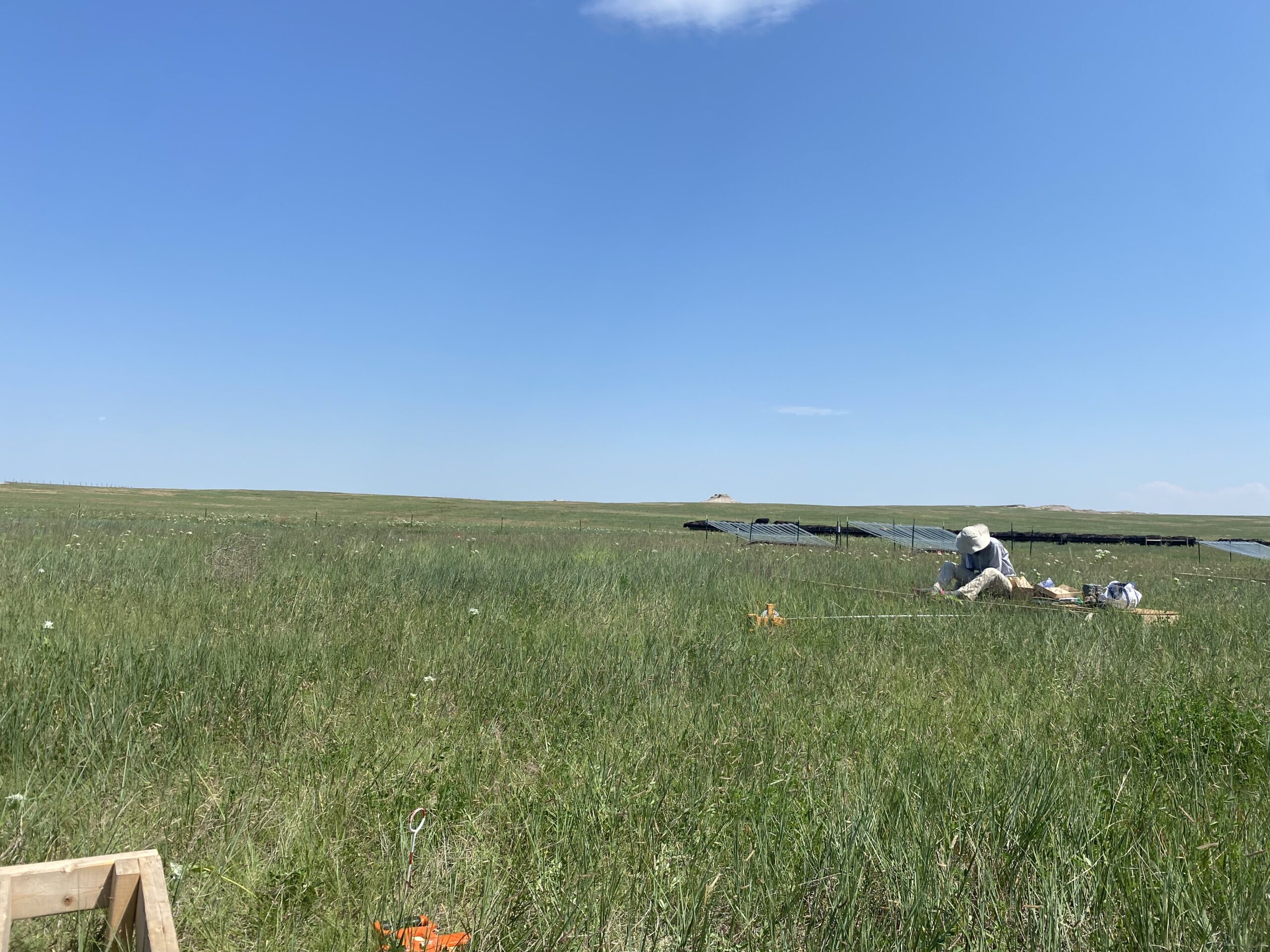

The crew visited Seney National Wildlife Refuge in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula at the end of July. We also went on special mission to Whitefish Point which is managed partially by the folks at Seney NWR. They just put in a new parking lot at the Point, and plan to landscape it with native plants. So, we had the opportunity to botanize and collect seed on in dune swales of Lake Superior, and take an after work dip in the lake!

While at Seney proper, we saw lots of Fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium), a species I don’t think I’ve seen east of the Mississippi.