“The vastness of the grasslands inspires the openness of spirit”…

This seductive, ecophilic line echoes through my mind every time I lift my head from my work. Laying on my tummy, eyes immersed in the damp understory of the prairie, the sudden panorama of the grasslands stretching for miles around me keeps catching me off guard. At the horizon, Paha Sapa (the Black Hills) border our Hay Canyon research site, and the sedimentary formations of Mako Sica (the Badlands) border Cedar Pass. The effect of this setting on the nervous system is immense- I remember to breathe, I’m filled with gratitude, I feel myself smile. My coworkers and I echo to one another, “it is so beautiful here….”

I’ve thought a lot about the experience of wonder in everyday life while working here. Wonder in the everyday has been a growing theme for me over the last five years exploring the shores of Gitchi Gami (Lake Superior), and now living in Paha Sapa. Growing up, before I realized I could make a career in the outdoors, such experiences of wonder were novel. Visiting Paha Sapa and Mako Sica as a pre-teen with my family came in the form of a packaged vacation experience, complete with Mt. Rushmore and Devil’s Tower voyeurism and starkly colonial narratives. These trips of course contained stunning views and showcased feats of human and nature’s ingenuity, but always ended with a return to the ugly, concrete smothered suburbs of home, and the immersive wonders of nature would soon fall from my mind.

This last week, working solo in the field for 7 hours a day snipping and sorting grass culms, I listened to the audiobook of “The Body Keeps the Score” by B. van der Kolk, M.D. This book is about how trauma shapes our brains and bodies. Van der Kolk explains the disassociation that defines trauma; how our brain’s alarm systems become overwhelmed by incomprehensible stress, beyond our range of biological tolerance, resulting in permanent changes to our physiological functions. The experience of wonder is fascinating to compare- Similarly to trauma, wonder occurs when our experience is beyond what our brains can tolerate and what our minds have frameworks for. Both trauma and wonder occur as an involuntary surrender to incomprehensible experience. Neuroscience explains how both states stimulate the vagus nerve and the same areas of the brain, but in different ways; the effects on the body and spirit seem to be opposite.

Trauma creates a constant sense of danger and helplessness, trapping us in an over-active self-preservation mode that weakens our immune systems and internal functioning. It transforms our worlds into small, self-centered ones where we are in opposition to all. Wonder also transforms the way we see ourselves, making us small, but this occurs in a quiet, humble way. We feel small because the world around us is so grand, mysterious, and deliciously incomprehensible. We are struck by the sense that we are a tiny yet integral part of a greater whole. This connection to the Other and the All fosters peace within our minds and bodies, makes connection to others not only possible, but a driving and undeniable force of life. I see myself reflected in each flower, insect, lichen, cloud, and breeze.

Working outdoors and in ecological fields gifts me with wonder daily, though this is something I’ve had to work hard to access. Studies show that one of the prime ways humans experience wonder is in the moral beauty of others. Growing up, the philosophy of life on earth was presented to me in a “man vs. nature” way, the moral ugliness of which fostered misanthropy. I saw all the ways we interacted with nature as destructive and extractive, as if our role on this planet was antagonistic and hopeless. But education and commitment to ecological study requires in-depth understandings of land-management policy and guiding moral philosophies across time and different cultures. It reveals the multitudes of ways humans have co-existed with and stewarded this planet and our fundamental connection and roles in our home ecosystems.

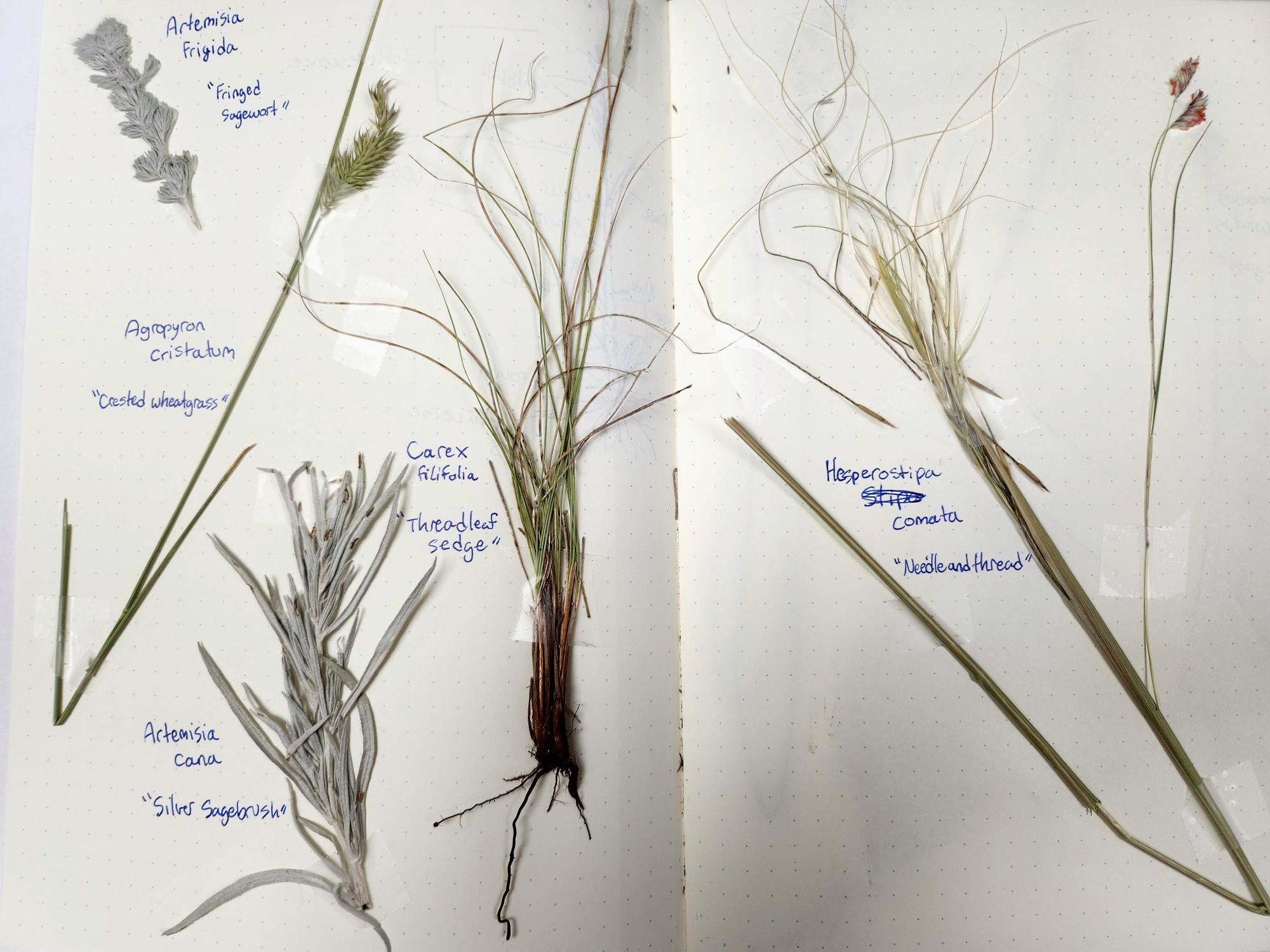

We work with two Doctors of plant science. I collect such mentors gratefully, learning about how to exist sustainably in this work and taking note of the inspirations and drive of different personalities committed to land stewardship. The quiet confidence and gratitude in one another’s work is reassuring. Working along these professionals is an important reminder that as individuals and as a species, humans have always found life-sustaining meaning and relation to the plants around us. We are no less dependent on them physically and spiritually today than our ancestors were. The moral beauty of these understandings, guided largely by Indigenous wisdom, yet present in all humans, guides my daily experience and often leaves me at a loss for words- pure awe in the wonder of it all.