Filled with excitement and nerves, embarking on this journey had me filled with a concoction of feelings. I was to return to my home state and have my first taste of my desired career. Although I had made many amazing new friends during the CLM training at the Chicago Botanic Garden, I quickly realized how much I would be learning this season. I encountered feelings of doubt and imposter syndrome as we attempted to key out dried flowers. With no formal botany experience or education, I began questioning whether I knew enough about botany to be a successful seed collector. In the few weeks between the training in Chicago and my arrival in the Chugach National Forest, I prepared myself to acquire a plethora of new knowledge. Foraging throughout my life had nurtured a connection with many native plant species, but I only knew them by their nicknames (common names). These first two weeks back in Alaska have been a whirlwind of learning and reconnection. After being away from Alaska, returning to the land and the landscape I love has been grounding and exciting. It’s like reuniting with an old friend.

Week One

During my first week, I spent a lot of time completing online training for the Forest Service, much of which was your typical large agency type stuff. A few Alaska-specific pieces of training rang of nostalgia: the bear safety training and boating training. Not a single day was spent exclusively chugging away at required training, though. On day one, my field partner, Maggie, and I visited a potential collection site for scouting. I quickly learned how niche much of my plant knowledge was and how little I knew about the plants that occur on this side of Cook Inlet. I spent several summers studying species that occur in muskeg land as a guide in my little free time, but this was a new ball game. She was kind enough to guide me through the resources she had been using and patiently guided me through much of the jargon.

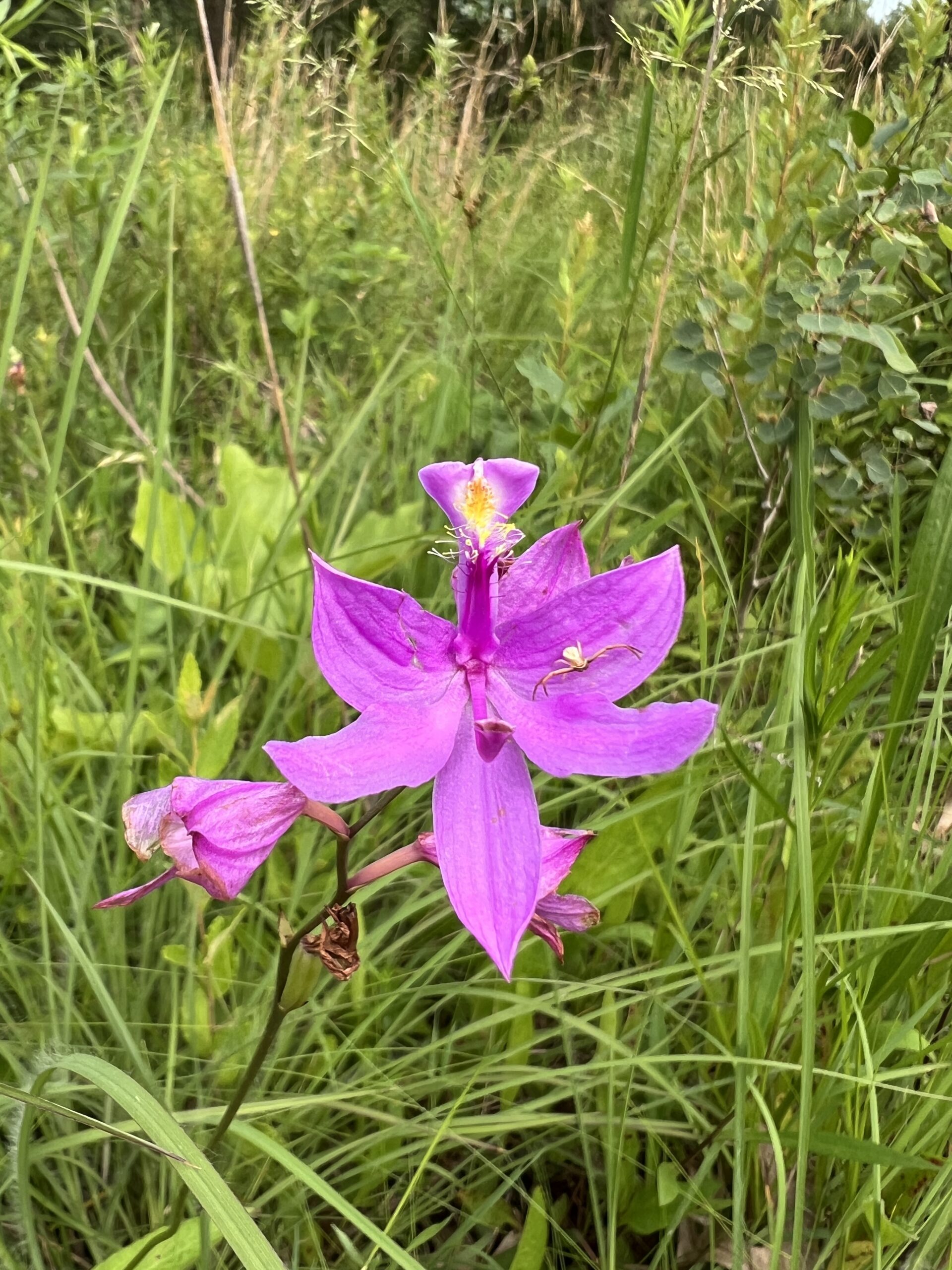

The next day, we spent a few hours IDing some plants in the field with our Forest Service mentor. On our journey, we stumbled upon an old friend – drosera rotundifolia in a muskeg surrounded by peat moss, a few patches of cotton grass, and a few orchids. Finally- I am home.

Wednesday was an inspiring day. I spent half the day shadowing my mentor and learning about the processes the Forest Service goes through to start a new project. So many experts are involved: archeologists, botanists, wildlife ecologists, parks and recreation specialists, engineers, and hydrologists! (I am sure I am missing a few as well.) Witnessing their conversation and collaboration drew me in.

The second half of the day was spent meeting the restoration site, to which much of the seeds we collect this season will contribute. I enjoyed witnessing the conversations between experts and how many people are involved in a project of that magnitude. The Resurrection Creek restoration project is in its second phase, and WOW, is it a big one. Seventy-four acres of riparian habitat are being restored in this project as they return the creek to a meandering, salmon-bearing system. I was privileged to meet and witness the SCA interns watering and maintaining the willows and sedges that have already been planted as part of the restoration project.

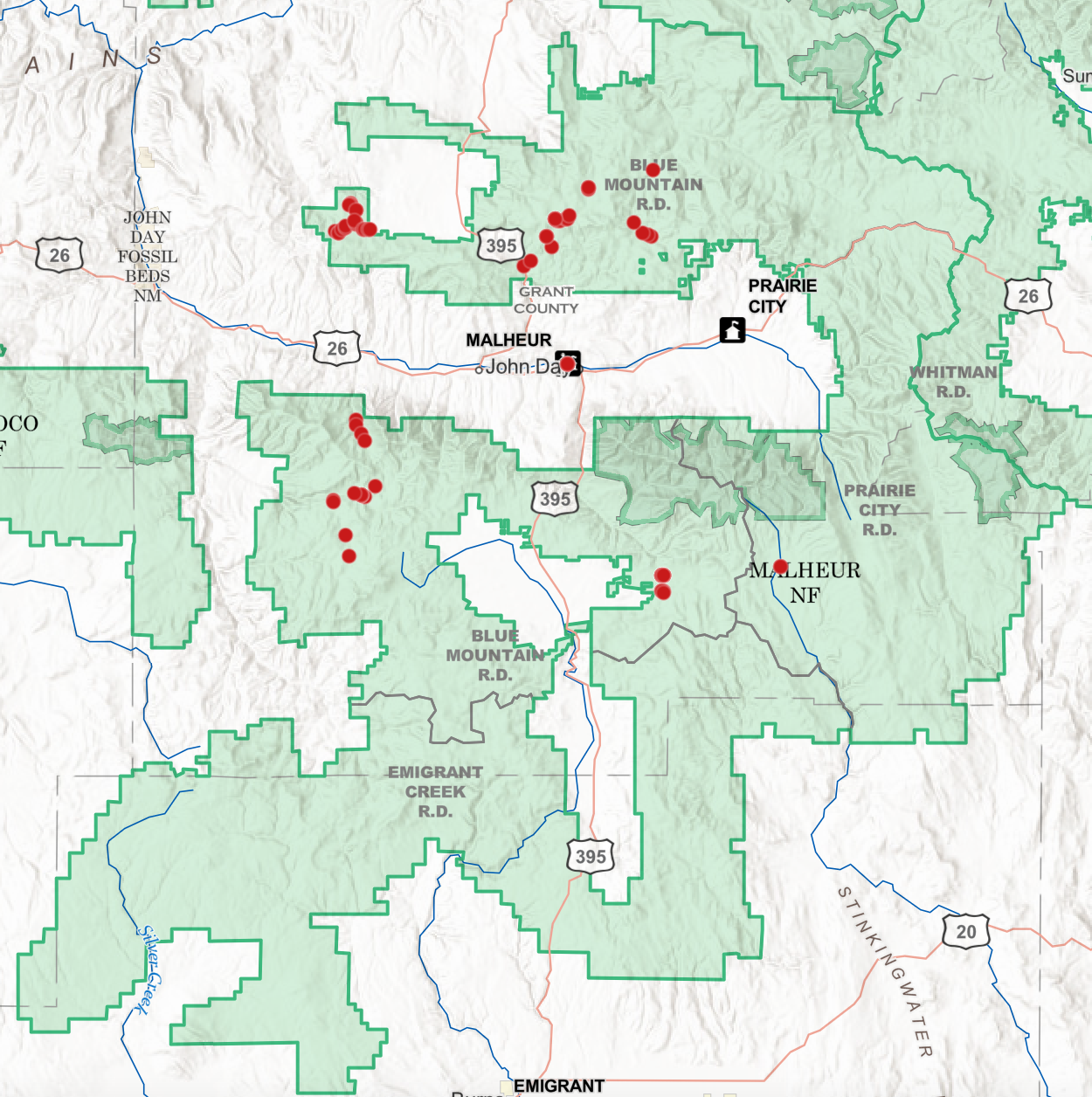

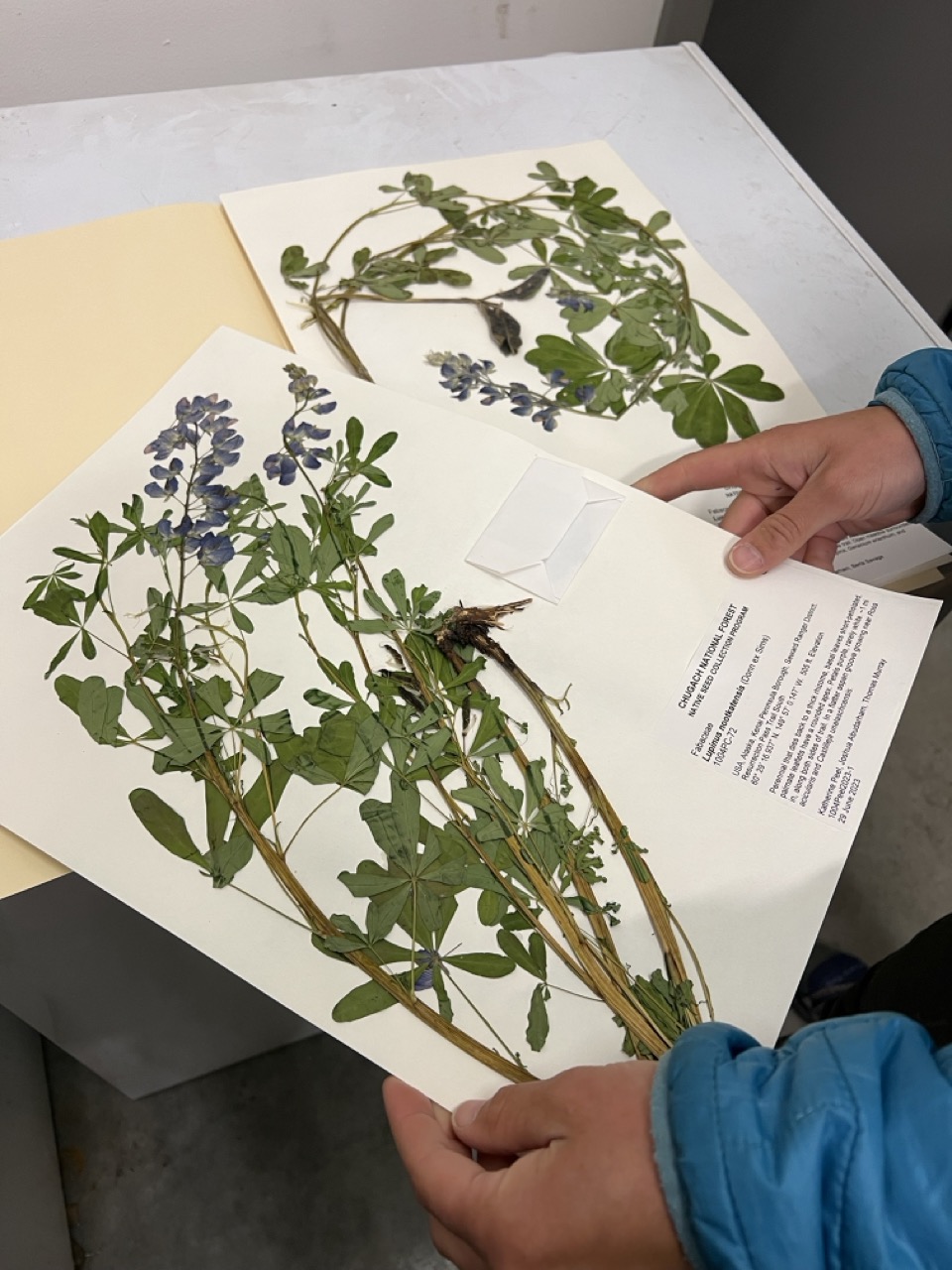

We dedicated much of Thursday to intimately getting to know the Chugach National Forest Herbarium as Maggie and I filed away vouchers from last year’s interns. Filing the vouchers allowed me to learn more about the taxonomy of many plants that I had previously only known the common names of and an opportunity to practice saying some whacky Latin names.

We dove deeply into new references and keys with our mentor on Friday. We had more sources than I could have dreamed of!

Week one was a whirlwind of learning, excitement, and reconnections with my roots. While a significant portion of my time was spent in front of a computer, the other half was a thrilling journey of learning new plants, receiving invaluable advice from my mentor, and establishing a harmonious working relationship with my field partner. The excitement of learning was palpable and inspiring. I savored my free time visiting harbors full of nostalgia and hiking new trails, each step reinforcing my connection to the environment.

Week Two

Week two was full of adventure and connection. The work days were primarily spent in the field, scouting and practicing keying plants (mostly sedges). The evenings were spent connecting with new friends and bonding with my co-intern. We learned about all the exciting gadgets and tools we will use for collection, such as a seed sorting machine, which will help us efficiently clean the seeds we collect, and a funky seed collection tool, essentially a modified weed whacker designed to collect seeds rapidly. I can not wait to dive deeper and play with those later in the season!

So far, my favorite day of the season occurred that Tuesday and was full of spontaneous experiences. We were invited along on a Dall Sheep survey that morning, and again, I experienced nostalgia as we ventured out by boat on Kenai Lake- one of my favorite water systems to go out in. We were greeted by beautiful weather and several sheep on the cliffside. We witnessed the incredible blue glacial waters of Kenai Lake shine in the sunlight from shore while practicing plant ID and looking for Rams along the mountainside. We were out in the field for the second half of the workday, where we successfully keyed out a tricky sedge!! What a gratifying experience that was! That evening, after clocking out, we were invited to kayak and cold plunge on the other end of Kenai Lake with some new friends, and yet again, I felt at home on the water. These spontaneous experiences, from the unexpected sheep survey to the impromptu kayaking trip, not only added excitement to my days but also deepened my connection to the environment and the people around me.

Each day has been a new experience filled with new knowledge, a deeper connection to my home state, and new connections with people who make me feel more at home than I ever have in Alaska. The imposter syndrome I felt at the beginning of this journey has been soothed by a profound sense of belonging and a yearning to learn and experience more. I can’t wait to see what else is in store this season, and I’m excited to share this journey with you.