The past 5 months working at the San Bernardino National Forest have been filled with so many amazing new experiences. While I didn’t move states away (or relocate at all really) for this internship, this summer has allowed me to meet these familiar mountains in a whole new way.

On the very first week working here, I realized that the team I was becoming a part of was filled with so many knowledgeable people ready and eager to share their knowledge with us. From botanical and wildlife knowledge to some of the forest’s best views and swim holes, everyone we worked with opened up to us and made us part of the team. It’s hard to encapsulate all of the things we learned this season and it would be impossible to mention all of the great moments we’ve had. So here are some parts that stand out to me:

Rare Plants!

Early on in the season, we got to do a lot of T&E plant surveys! While a lot of the plants that we worked didn’t have the big showy flowers that many people think of when they’re talking about cool flowers (except maybe Lillium paryi), the plants we worked with had a subtle beauty and unique characteristics you might miss if you aren’t looking for them.

These are just a few examples of the rare plants we surveyed this year. I don’t know if I’ve ever unknowingly walked past these plants during my past visits to the SBNF, but I’m glad to say I won’t in the future. A huge thank you to Joseph and Katie for sharing so much knowledge with us out in the field, and to Scott Eliason and Drew Farr for being great resources to us whenever we brought back common plants to key out.

Mulch!

Another great part of our season was getting to work at the Green Thumbs restoration events. It’s been so great getting to meet so many people with a passion for working with plants. Our biggest event this year was National Public Land’s Day and it was extra special because of all the prep work. Some of my favorite moments on this forest were actually on the days I spent shoveling mulch with the team! Thanks Koby and Diego for taking us under your wings and always being such a blast to work with :’-)

Seeds!

And of course, the seed collecting. The whole reason we’re here folks! When I learned about the work we’d be doing during our training in Idaho early this year, I was so excited to get out here and be around plants all day. The seed collecting we’ve done this year definitely lived up to my expectations. It’s been so fun being out with Ana Karina and our team collecting seed and working with people who are just as happy to be out there as we are. When I look back at all of the collections we’ve made this year, it makes me think about how quickly the time flew. One minute you’re collecting some of the first seeds of the season (like those of Ericameria linerifolia) and the next you’re on to some of the last of the year!

Beauty all around us

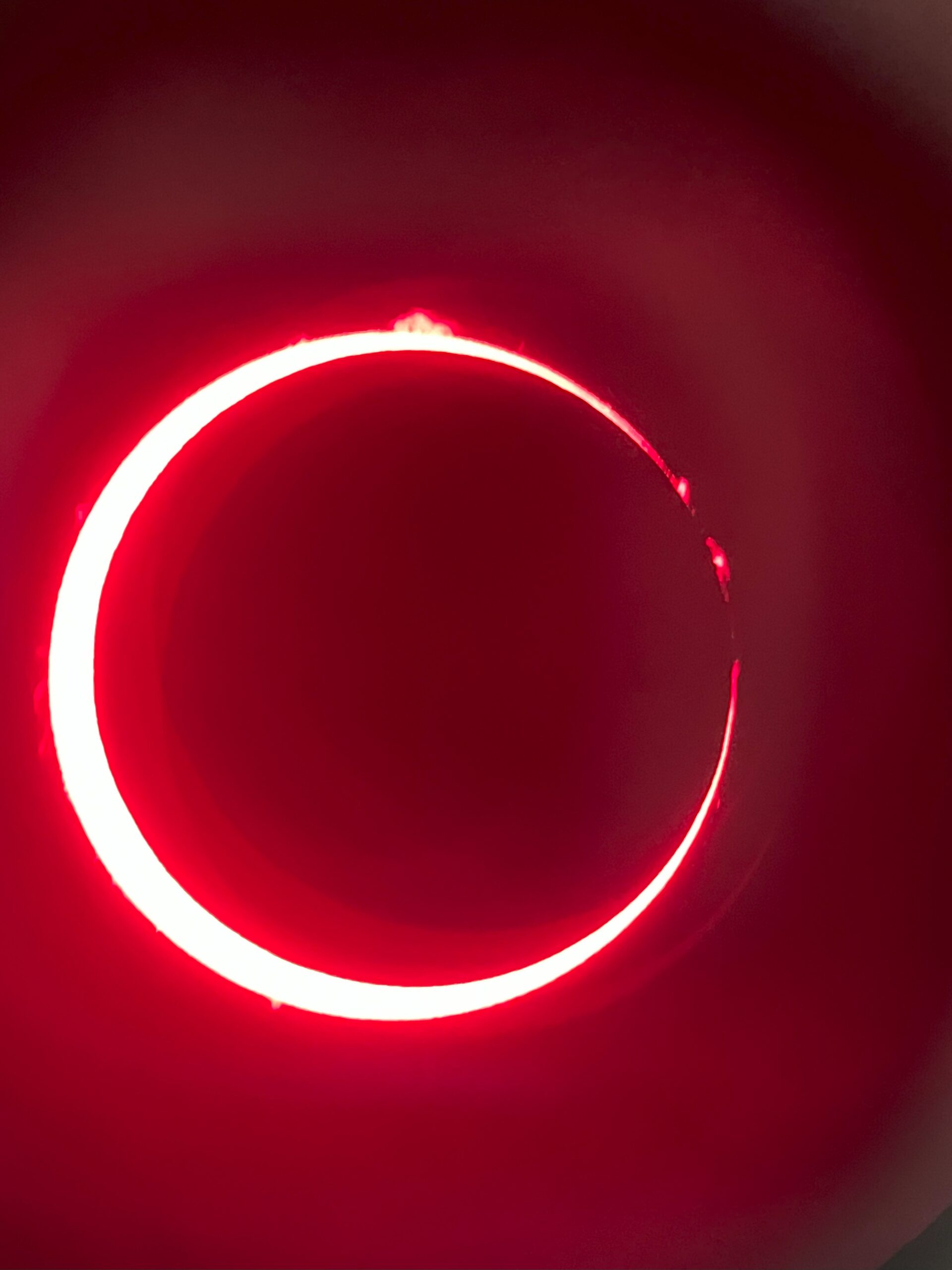

But, overall, some of the most memorable things I’ve done have been to sit in awe at the amazing views our forest has to offer. I didn’t get to capture every moment, but here are some pictures of a few of the best views and places I’ve visited this year.

That’s a wrap on this season! Endings are always so bitter sweet. But, I’m hoping this isn’t a goodbye to the SBNF and more of a “see you next time”. Thanks so much CBG for the great opportunity and for all of the doors it’s opened for me. I couldn’t have asked for anything more out of this experience <3