All too often, I see bright, passionate young people jumping into graduate programs right after their undergraduate degrees. This might be the best choice for some, maybe even a majority, but I’m sure many have also felt the pressure to go to graduate school because you know school is something you’ve been good at, it’s a sure plan, and it’ll buy more time for things to fall into place. I decided during my last year of college that “might as well” wasn’t a good enough reason to go to school for two to four or more years and decide on the niche I would study and fall into the rest of my life. Instead, I have been forging my own path to test out my interests and desires and see what sticks. My adventure started with a year living in Germany, becoming an ESL teacher, and then moving to Las Vegas to try out van life while working for Nevada Conservation Corps. While in Las Vegas, I learned so much about the people in conservation that make all of the concepts and theories that I’d learned in the classroom come to life and the diversity of jobs that it takes to make it happen. Originally from Ohio, I decided I wanted something a little closer to home this summer and fall, and I landed at Ottawa National Forest.

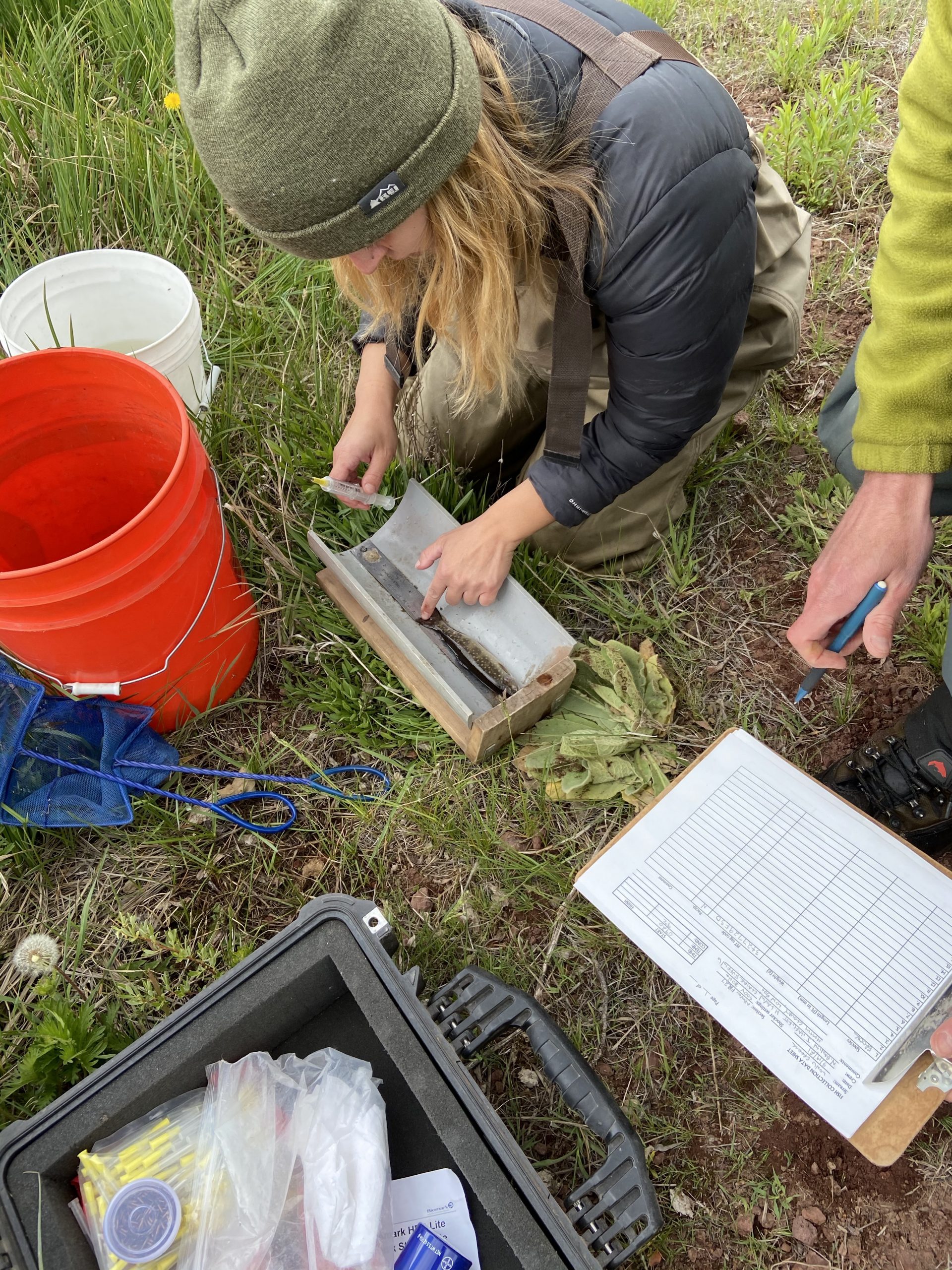

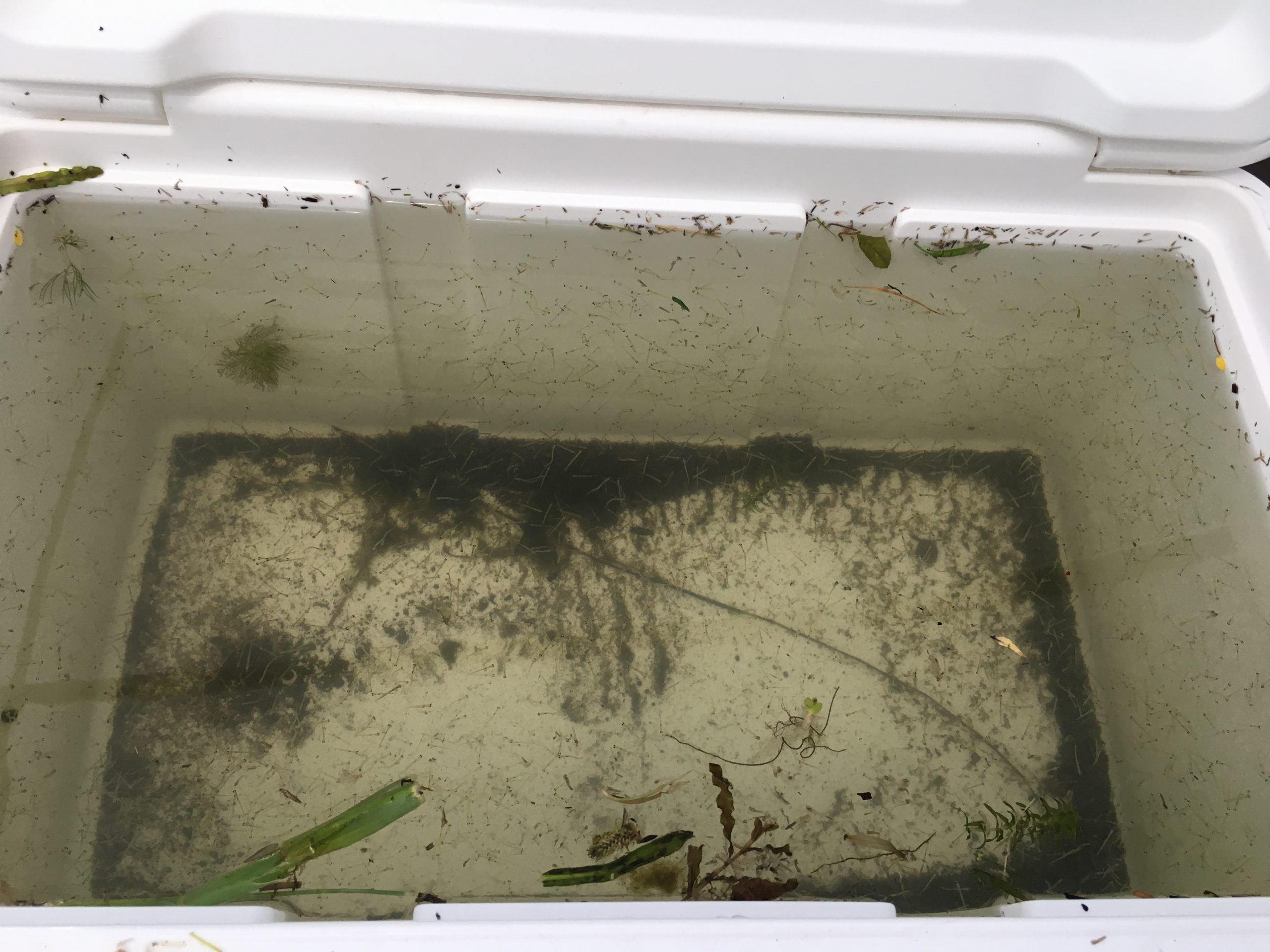

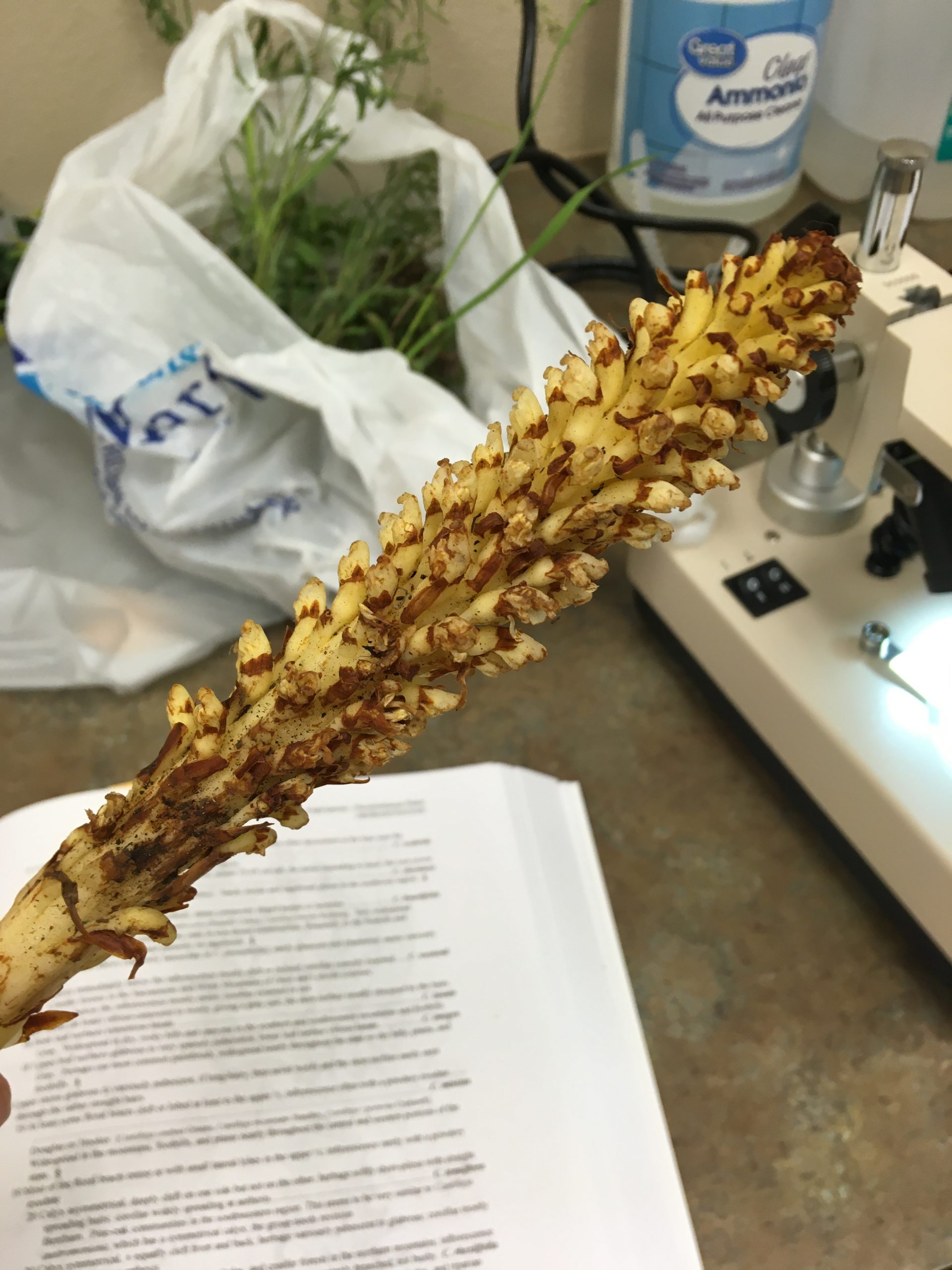

When I arrived, I was immediately charmed by the small town of Ironwood and awestruck by the towering pines. The John Muir quote “Between every two pine trees is a door leading to a new way of life,” came to mind, and it has stuck with me ever since as I stroll and tromp between pines to get to our work sites. I am on an invasive plant crew at Ottawa National Forest, and after a few weeks, I finally feel like I have settled in a bit. Like many other jobs where nature is the office space, our typical day is tricky to pin down. Some days are straightforward: show up to the office, get your maps, get to as many sites as possible and thoroughly look for and treat the invasive species there such as garlic mustard, honeysuckle, Japanese barberry, glossy buckthorn or goutweed. Other days leave me completely open-mouthed that this is my real life and I’m getting paid to do this: try on the wet suits and go snorkeling for Eurasian watermilfoil.

When starting a new job, I think it’s important to set goals, and what better place to write them down than a blog post for all to see and read. My biggest professional goal, which I have already made huge strides in, is becoming a better navigator. I tend to rely on my phone for GPS quite a bit when I’m driving in my personal vehicle, and I couldn’t tell you which way a road runs. However, invasive plant sites aren’t nicely saved into Google Maps, so we have to use our paper maps to navigate the dirt, sometimes overgrown Forest Service roads. At first, I was nervous about navigating, afraid to take us down a wrong road. I quickly learned two things– 1.) That it’s not the end of the world to make a wrong turn and 2.) How to make less wrong turns. I’m excited to see how my navigation skills will improve by the end of this internship!

Most of the other goals I have are personal and some of them not directly work-related. Here are a few: see a wild bear, catch a fish, see a rare plant, learn and be able to ID 20 new plants (this number will only increase, as I’m learning new plants every day in the dense and diverse forest), and form new friendships while I’m in Ironwood. In the coming months, there’s a lot I’m looking forward to, the change of season with the spectacular colors of the trees, the different invasive species projects, learning about the innerworkings of the forest service, and of course getting to know my co-intern, Emily, and supervisor, Ian, much better. Field work can be challenging, especially because nature doesn’t care if you’re already covered in mosquito bites and your socks are wet, but even through long, itchy, soggy days, Ian always has a smile on his face and arrives the next day chipper as ever, excited for work at 6 am. It’s an enthusiasm Emily and I have taken note of and hope to emulate even a fraction of. There’s still a lot of adjusting I have to do before I feel like the forest is a second home to me, but I’m finding doors to a new way of life every day. Each one starts to feel a little more welcoming and familiar than the last.

Tessa Fenstermaker, Ottawa National Forest