3 observations from this past month:

A thin layer of moss sits at the sill of the botany truck window. If you roll it down, you can run your finger over the soft mat of vegetation, sometimes still wet from rain.

Fallen trees contribute to the soft hills of the mossy understory. If one has been there long enough, placing your weight on its decaying wood will leave you finding yourself falling through to the other side, where water in some form awaits.

With the right timing and luck, you might witness black bears eating grass. Or berries and deer. Or rotten salmon.

It is strange to think that I will only be in South East Alaska for one season, one summer. Especially when echoes of the year-round adaptations which have formed this rainforest are everywhere, so long as you take a second to look close enough.

Summer is go-time for everyone and everything here. Animals, plants, and Forest Service employees alike are all desperately trying to succeed in a frenzy of organized chaos, accomplishing tasks they’ve been waiting to do all winter long. Fishing, hunting, and foraging abound. Fawn learn how to walk on shaky legs. Plants expend energy producing colors and smells to tell the right pollinator where to land, and what animal it would like to poop out its seed. Fungi must spit out their mushrooms before it’s too late.

A common goal sweeps through the area and permeates the air like fog. It challenges us. Achieve, and prepare. Because, as the Starks would say with furrowed brows and foreboding seriousness—winter is coming.

It would be a mistake though, to interpret this goal as a reason to not appreciate the land, especially at the height of its liveliness, for all of its beauty and quirks. How else might we learn from it? For example. Large, fleshy fruits are not found in the plant diversity here. The Tongass National Forest Botanist (and my supervisor), Val, points out that this is likely the result of a short growing season, too little heat, and too much rain. All of which make such an endeavor not worth it to many plants. Why attempt to make a fruit that may not have enough time to fully mature? Or even worse, to put all your carefully stored carbohydrates into making one that could rot before it ever gets eaten?

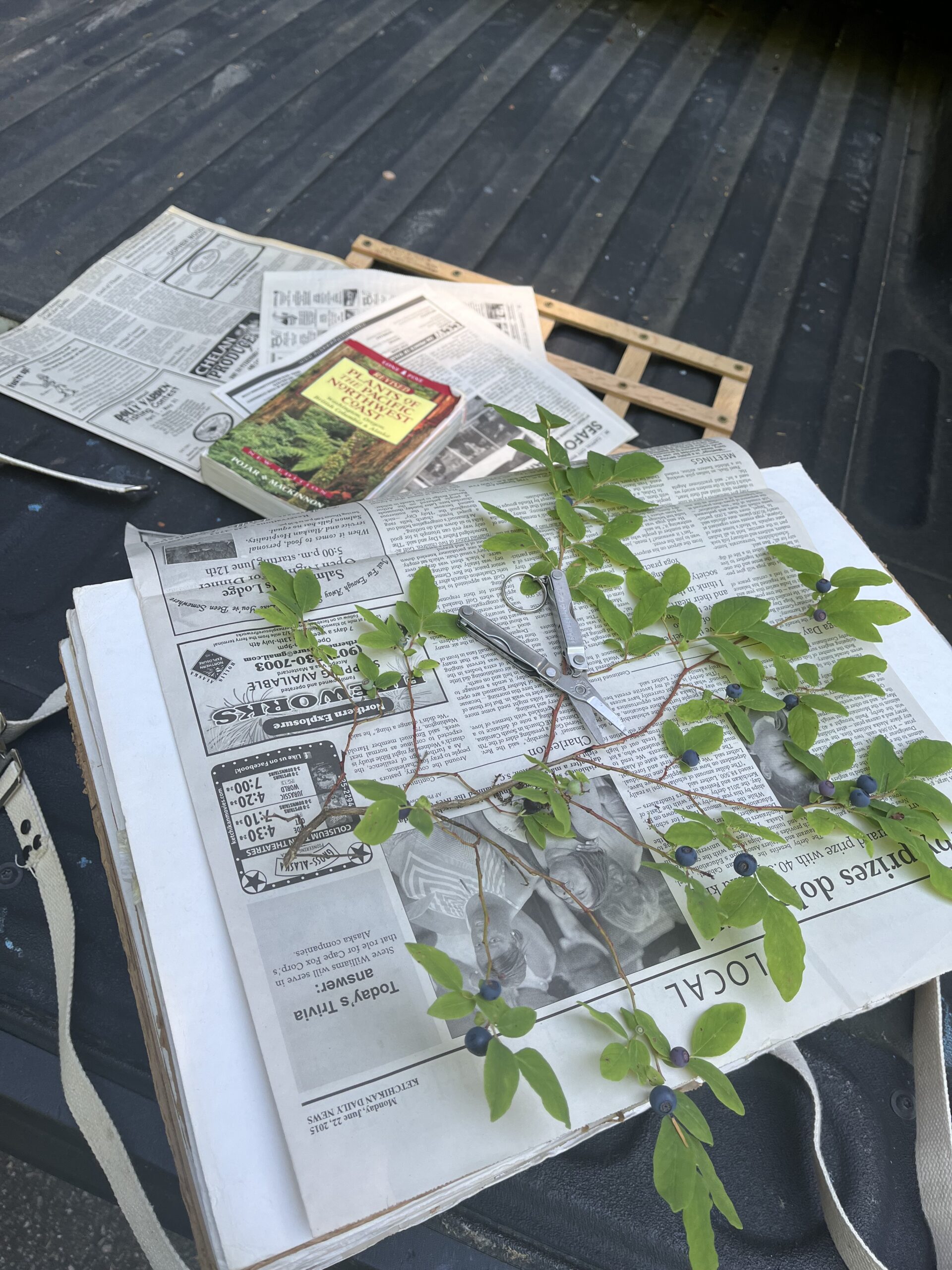

Consequentially, I have picked more berries in the past month than I have my entire life. As of now, the list stands at: blueberries (three kinds), salmonberries, five-leafed bramble (a tiny kind of raspberry), (red) huckleberries, thimbleberries, (stink) currants, and (red) elderberries. Each one of these fruits measures smaller than my big toe—but (with a bit of plant anthropomorphizing,) this trend towards the tiny-and-mighty makes complete plant sense.

In this part of town, plants with fleshy, edible fruits know that any large animal able to carry your seeds to greener pastures will be on hiatus once the warm-ish weather leaves. So you’ll need to put out fruit, fast. Or at least as fast as you can, for a plant. Hence, small fruit. And a lot of them, to not only make it worth the bear’s while but to present perhaps a bird or mouse with the opportunity to take some of your seeds as well. Maximize your odds. Put lots of seeds in those fruits while you’re at it. Small fruits mature faster, and require less energy per unit. So even if one or two of them develops mold, it’ll hurt less. The risk of missing your opportunity to continue your genetic line is minimized. Plus, the ants will happily carry those leftover berries away, anyhow.

It is, figuratively and literally, the small things like this which allow me to endlessly marvel at the workings of ecology. Alaska is a prime example of how abiotic factors influence the dynamic of living organisms. How it has forced them for thousands of years to figure out a way to work in tandem with one another through stresses, all towards the basic endeavor of survival. Ecology reminds us that nothing which persists in nature does so in isolation. Especially not here.

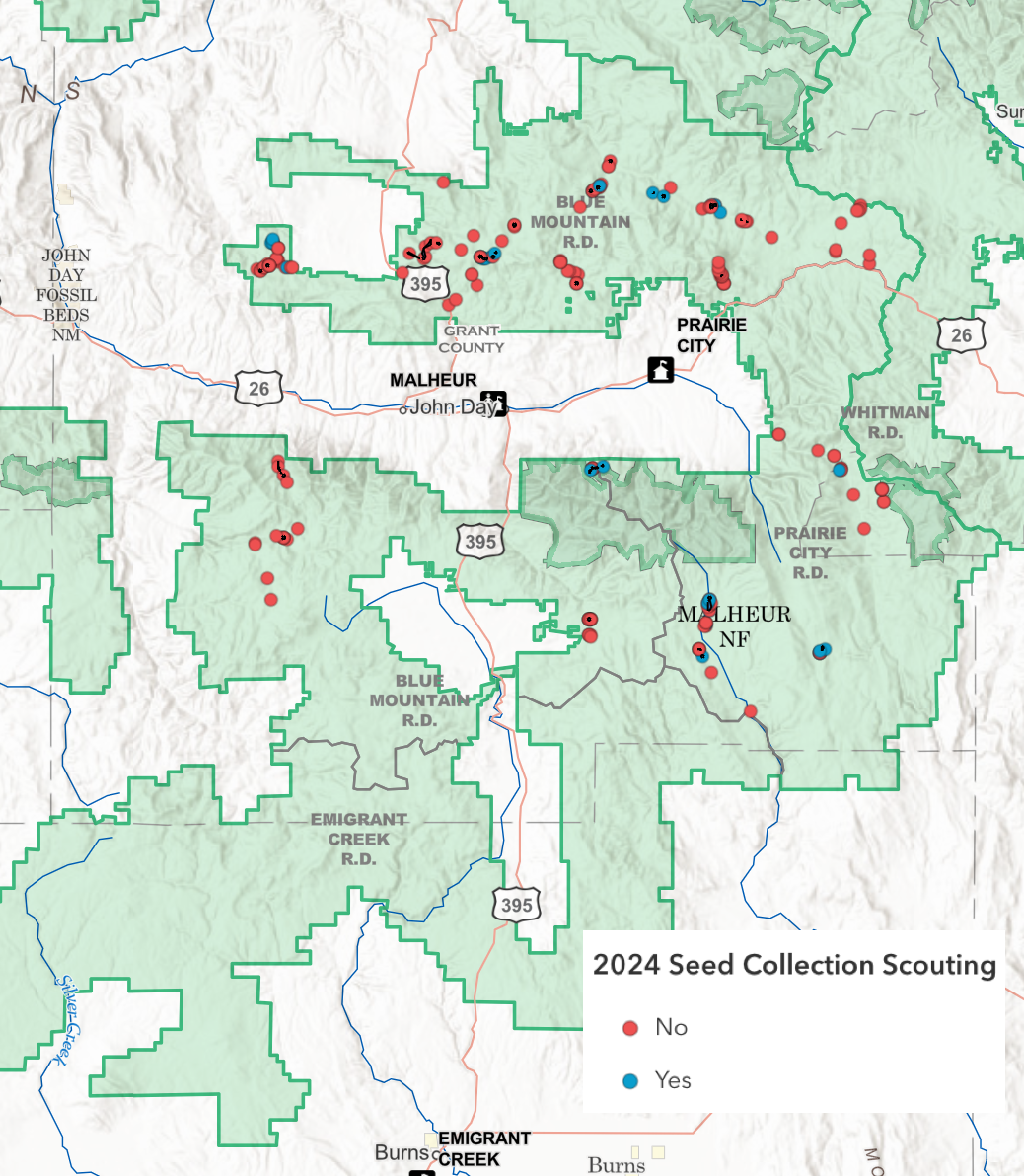

This same reason is why Levi (my field partner) and I work to collect a diversity of seed. Because no one truly understands, at least not yet, how exactly that web of organismal relationships operates, or how intricate it might reveal itself to be if it is teased apart. And we risk losing it all, forever, if we continue to ignore that fact. From the berries, to the sedges, to even the stubborn seed pods of western meadows rue that refuse to ripen; there is merit in appreciating seeds of the entire native community, even if limitations force us to prioritize a subset. Who knows where we would be without them?

See you next month,

-Emma