It seems like all of a sudden it is the end of July. The fireweed started blooming about a week ago, marking the height of summer. Some days, when it’s rainy and cold for days on end, I have to remind myself that it is actually the middle of summer. Sunny days are like gold here, where everyone tries to take full advantage of them and they are not taken for granted. The other day I heard the wind blow through the aspens and they seemed to say that fall is drawing near. The seasons go so quickly in Southcentral Alaska, it’s astounding. These urgent reminders of time passing are also reflected in the plants which seem to appear full grown suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere. I try not to feel anxious, but these signs tell me that our seed gathering season is right around the bend and it will be go time any day now.

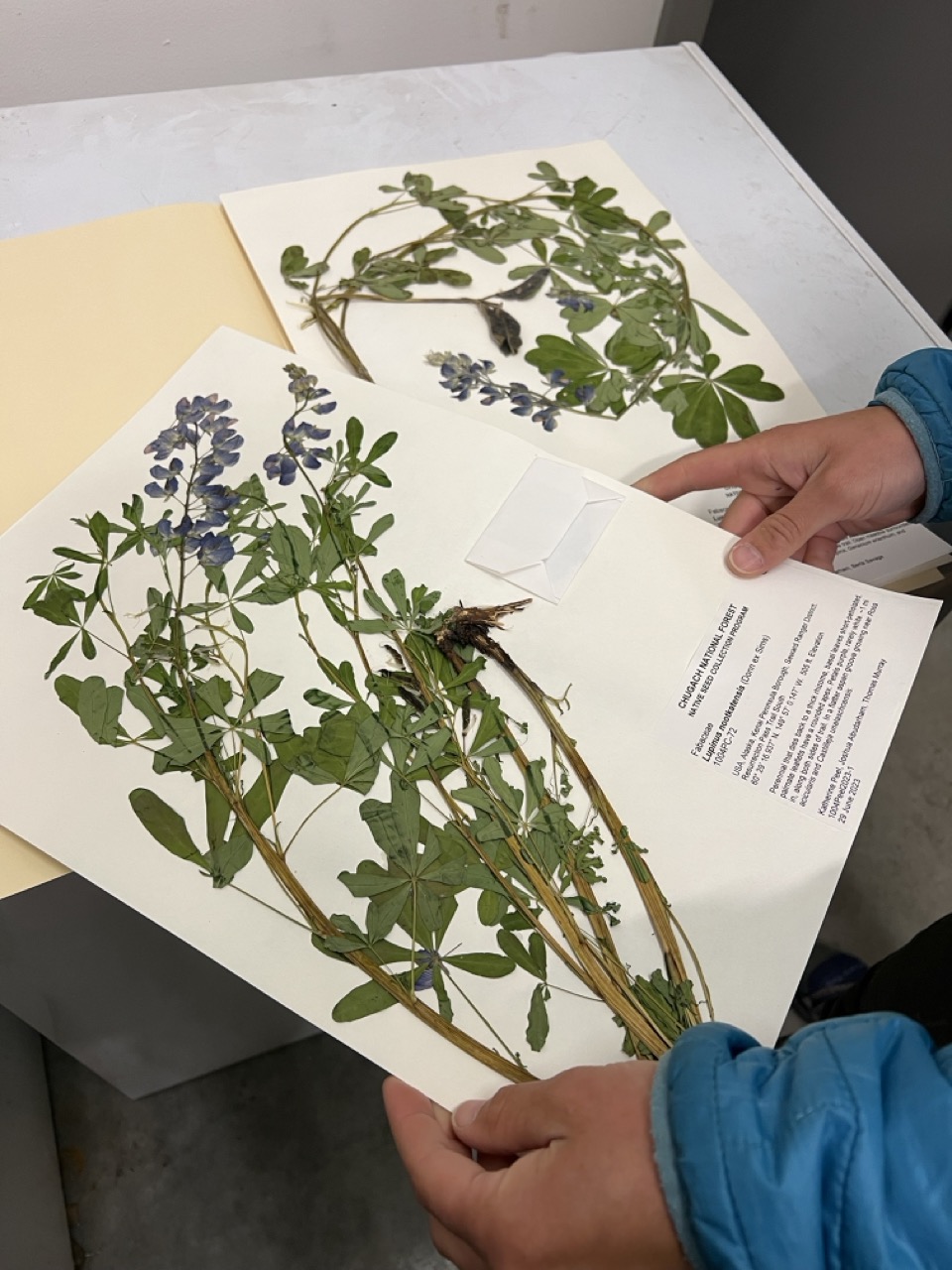

This past month has been a crash course into the native flora of the Chugach National Forest on the Kenai Peninsula. I’m pleased with the amount I’ve learned over the past two months, and grateful to get to know an area through this lens. I remember when I got here in the end of May, I maybe recognized three to five plants. Now when I walk through the forest I see dozens of familiar faces. The list of ~30 priority plant species along with their Latin names that our mentor Peter handed us the first week sent my mind spiraling at the time. Now my co-intern, Sam, and I are using their latin names left and right as we hunt for good patches of them to harvest from, map their size and location, and dig voucher specimens to help confirm the ID of the plant before putting in an herbarium later on.

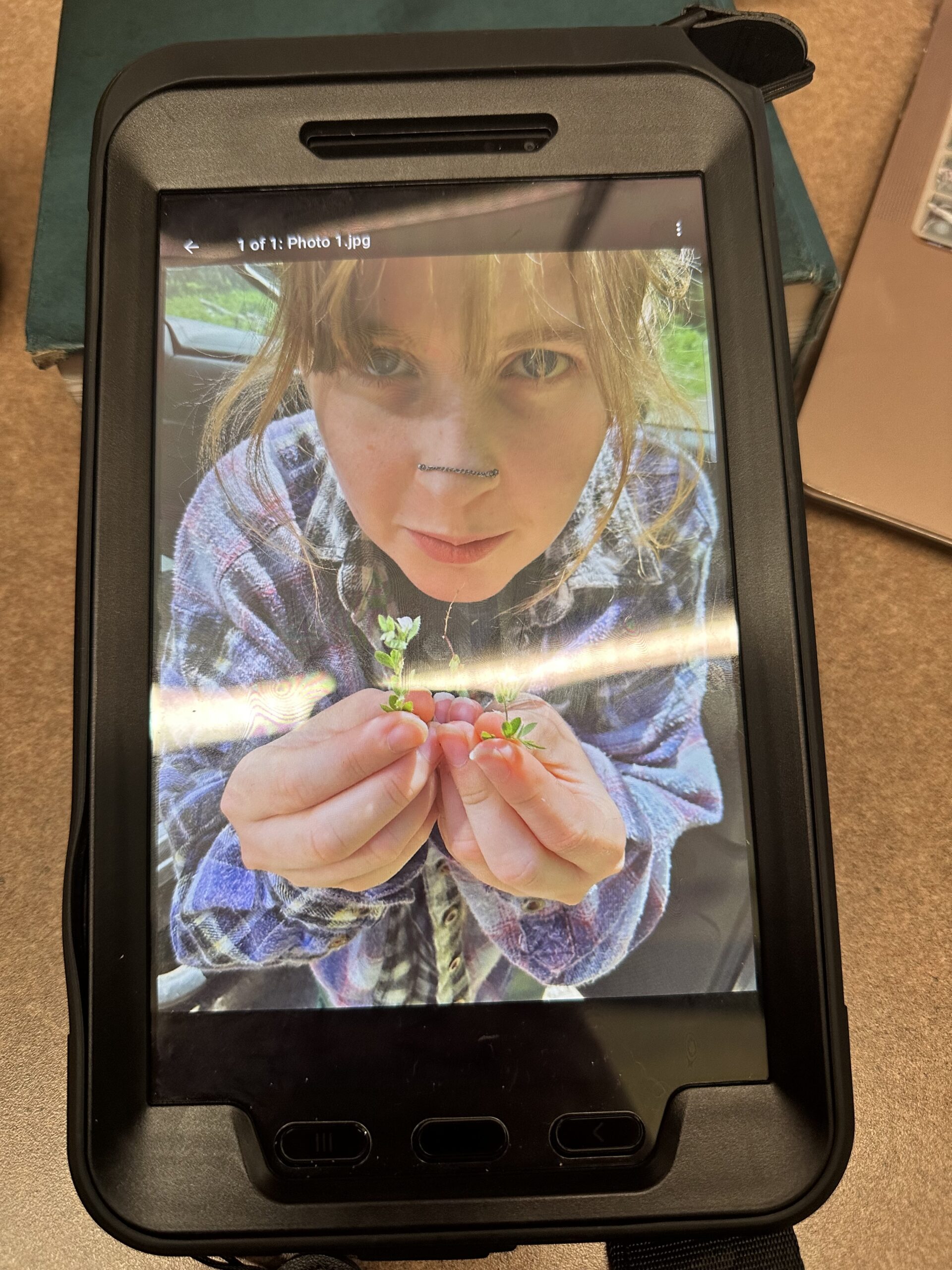

At first, Peter, our mentor, wanted us to simply become familiar with the plants and ecological makeup of the region and so we utilized a combination of identifying plants through iNaturalist, an Alaska Wildflowers plant app, and keying them out with local floras (especially the grasses and sedges). Hands on experience makes such a difference in this step. Initially, I researched plants on our priority species list online before we went out and found them in the field. This type of memorization is quite taxing and not incredibly effective, though. Although not for the first time, I was reminded that that something special happens when you get to know a plant in person within its native habitat. A special type of memory and recognition lodges deep within the heart when I meet a plant in person that I cannot receive by putting information into the memory bank in my mind through a book or computer alone.

Valeriana capitata, Capitate Valerian. Vibernum edule, Highbush Cranberry. Elliottia pyroliflora, Copperbush. Arinica latifolia, Broadleaf Arnica. Eriophorum angustifolium, Tall Cottongrass. Aconitum napellus, Monkshood. Delphinium glaucum, Sierra Larkspur. Heuchera glabra, Alpine Alumroot.

I’ve been quite astounded by one of the first plants I noticed in Alaska. When I arrived here in the end of May, just as the plants were beginning to grow, there was an odd thick green pad growing from a woody, spiny stalk at about the height of my knee. It surprised me, as it almost looked like a cactus. I was very drawn to it and intrigued. Once it started growing past it’s sprouting/reawakening stage, this plant transformed completely, growing broad wide leaves larger than dinner plates, with incredibly spiny stalks that pushed up 7-8+ feet above the ground with a wing span beyond 10ft in diameter. I began noticing this plant everywhere, and later realized what a prevalent species it is to the region, abundant in almost every understory. I very quickly learned that the common name for this plant is Devil’s Club, due to the large spines that cover the stalks and leaves of this plant. With a latin name of, Oplopanax horridus, both of its names are teaming with intimidation. But despite the evil connotations embedded within its names, I have come to respect this plant deeply, due to its resilience, abundance, and formidable nature.

Additionally, I’ve come to appreciate this plant the more I learn about its ecological functions and healing properties. Although the berries are toxic to humans, they are an important food source for bears. This is true to the extent that bears, more so than birds, have been found to have the greatest impact on spreading the seed of devil’s club, in turn affecting its population size and prevalence across the landscape. The plant is also said to grow in areas that have been disturbed by humans, especially those impacted by logging. Indigenous and local people utilize the stem and the root of this plant medicinally. It is said to have a wide range of potent healing properties, including a strong anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory.

Because we are working to restore a riparian area and build several wetland areas, the primary species we are looking to gather seed from are also riparian and wetland species. This includes many sedges and grasses, a couple rushes, and a few forbs. Thus, as a side effect of trying to find and identify the primary species on our list, my co-intern, Sam, and I have grown an unexpected love for sedges over the past month. Upon first glance, sedges aren’t as wow-ing as wildflowers or trees. But needing to utilize a microscope to key out these special plants has deeply developed our appreciation and admiration for these special plants.

First off, sedges are incredibly unique and gorgeous on a microscopic level. Their reproductive structures, otherwise known as the perigynia, are full of trichomes throwing light every which way and creating brilliant hues of subtle earthen colors. The perigynium, which encapsulates the seed, often has a beak coming off of it, from which the stigma emerges. The stigmas are also beautiful and feather-like. Some sedges have bisexual flowers and others have unisexual flowers, giving them vastly different and interesting appearances. Lastly, sedges, obviously, have edges, which never cease to amaze me with their triangular stem shape.

Sedges are also important to the greater ecological function of an environment. First, sedges are an important source of food for many animals in the area including bears, muskrats, mountain goats, musk oxen, geese, ducks, and insects. Sedges also provide crucial transitional habitat in the zone between aquatic and terrestrial environments and important nesting habitats for geese, waterfowl, raptors and songbirds, as well as habitats for macroinvertebrates. Some species provide important habitat and food for salmon. In additional to being a pillar of the food web and providing critical habitat, sedges also are important to warding off erosion, stabilizing riparian banks, and filtering out toxic material from the water. They remove pollutants and sediments from the water, improving its quality. Two of the sedges we are gathering the seed from – Carex lenticularis and Carex aquatilis – have been identified as an early plant successional stage plants. They are also deemed pioneer species of exposed mineral substrates that will persist indefinitely once established and limit the presence of other species.

The last plant that I want to highlight is another one that is on our list of priority species to gather seeds from. It has been interesting getting to know, within the broad category of riparian species, some more specific aspects and niches that certain plants prefer. This particular plant that I’ve been especially drawn to is named Angelica lucida, or Seacoast Angelica. It is a species that is native to this region but present only in certain areas. The first few weeks I didn’t see any. Then, one day when I was working alone and Angelica was on the top of my list of plants I wanted to find that day. During the middle of the day, I decided to sit down at a picnic table next to a lake to have lunch. I had been hiking around all morning, identifying and mapping plant populations near Trail River, finding interesting plants, but no Angelica. Then, as I sat at the picnic table, I happened to look over and there was one lone Angelica lucida standing regally in front of a tree. It almost felt like a joke or a beautiful coincidence, or something in between. And although I took pictures to confirm with my mentor when I got back, I had a deep surety that this was the plant I’d been looking for.

I have to say, I love it when this happens. When you’ve been looking for a plant for a while, one you’ve never seen before, you don’t know exactly what it looks like but once you finally stumble upon it there comes a deep surety, a deep knowing, bordering on intuition, that you’ve found it. I’ve since found this plant in select areas but it has definitely increased in quantity as the season has progressed. It seems to prefer a little bit more of either alpine conditions or proximity to seacoasts. I later found out that this plant also has strong medicinal qualities including being a strong antibacterial, digestive, and stimulant to the circulatory system.

As the blueberries begin to ripen here on the Kenai Peninsula, we are hastily mapping out as many populations of our priority species as we can before the seeds are ready. Based on phenology and timing of harvest last year, it seems the lupine will be the first that we will harvest, starting as soon as the end of this week. I presume we will then enter into a frenzy period where we will harvest as much as quickly as possible before the dormant period hits. I foresee quite a bit of harvesting during the next month, both in and outside of work. As the grass and sedge seeds ripen, so will the blueberries, salmonberries, nagoon berries, highbush cranberries, bunch berries, raspberries, and watermelon berries. Additionally, salmon fishing is in full swing here on the Peninsula, and I hope to harvest some of those as well. This next month is going to be a very wild and busy time, as we try to soak up the last strong rays of that warm golden light, and bask in the abundance that is so prevalent in Alaska this time of year!