Since last month, things have been moving along quite well, and quite as expected. We’ve started a handful of collections, and we’ve been keeping a close eye on scouted populations as we continue to keep eyes out for any new populations that may be coming up as summer hits us full force. As with any new job, there is a lot of information to take in and a lot of discrepancies in the small details as compared to other places. These small differences are easy to become acquainted with once you’ve become acquainted with them, and especially when you have kind and patient coworkers to help you along.

The same can be said for the plants. They are similar everywhere you go. You can see in most of them some familial resemblance that ques you into their relation. You remember the general trends and fashions of things, but it is the tiny details that can trip you up. Each key has different breaks that can cause trouble for us botanists. Of course each plant presents it’s own set of genetics that may or may not allow it to hybridize within its community and so on and so forth. The troubles you can run into are endless and all part of the “art” and the FUN of keying as many botanists, including myself, would tell you.

It turns out that much like becoming acquainted with coworkers, one can quite quickly become acquainted with the surrounding plant life. Running through the key each time we see someone on our list is incredibly fun. What is even more entertaining, and confidence-boosting is being so familiar with these individuals that we know which features to look for which set them apart from others. This also allows us to be more efficient with our time spent in the field, if we can pinpoint those key features. Many plants on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forests so far have been kind “coworkers,” if you will. Geum triflorum has three pronged leaves that make it obviously “triflorum.” Green gentian has green flowers as opposed to the white flowers of the other Frasera in our area. And Geranium viscossissimum is quite sticky and the only pink-flowered perennial geranium around, and G. richardsonii is the only white-flowered perennial geranium, so those are both simple enough to get to know.

I cannot say the same for Penstemon albertinus. Penstemon albertinus is like that person in the office who is incredibly shy and reserved, yet you know they’re REALLY cool, so you invite them to every party, but they are always busy doing other things and so you never get the chance to actually know them. Oh, and they have a twin named Penstemon attenuatus who often shows up to your parties, but you think upon first seeing them that maybe, just this once, it could be albertinus. The anthers are glaborus, the verticillasters are open. You note the acute tips on the stem leaves and hope it’s just a morphological difference. But as you get closer, you find the basal leaves to be quite thinner than Albert’s and you know you’ve again been fooled by Attenuatus.

When this occurs over and over, it can be quite frustrating, and makes you question your abilities as a budding botanist. In this case, we asked the botany techs based out of Helena. They so kindly invited us out for a couple days together in the field so they could share some of their experience and knowledge from four years on the forest. During this time, we did spend some time with Penstemon. Both Dayna and I were relieved to find that we are not the only ones Penstemon rejects. In fact, Nate mentioned there are many conversations had over the exact differences between the two species, and even with his four years of experience in the area, he still has to return to the details each year to refamiliarize himself with the need-to-knows. So we’ve begun to accept that we may just never be on very good terms with Albertinus. We may just have to take a key to this particular individual each and every time we meet in order to truly ensure we’re accurately identifying. Which is great practice and it makes you appreciate the more “firiendly” and straightforward plants all that much more, and forces you to really hone in on those botancial skills and instincts. I’m looking forward to finding more challenging individuals throughout the season, and hope to learn a lot from them!

Regional Work Requires Devouring Regional Delicacies

This season our Seeds of Success squad has been tasked with piloting a new Midwest Seed collection group, based out of the Chicago Botanic Garden. As this is a new agreement between the CBG and the USFWS, we have been tasked with navigating the territory that comes with a brand new project. Initially, we spent time reaching out to refuge managers, explaining the goals of the program and acquiring a target species list of around 150 species (and still growing :)), before meeting with many land managers and scheduling field work for later in the summer.

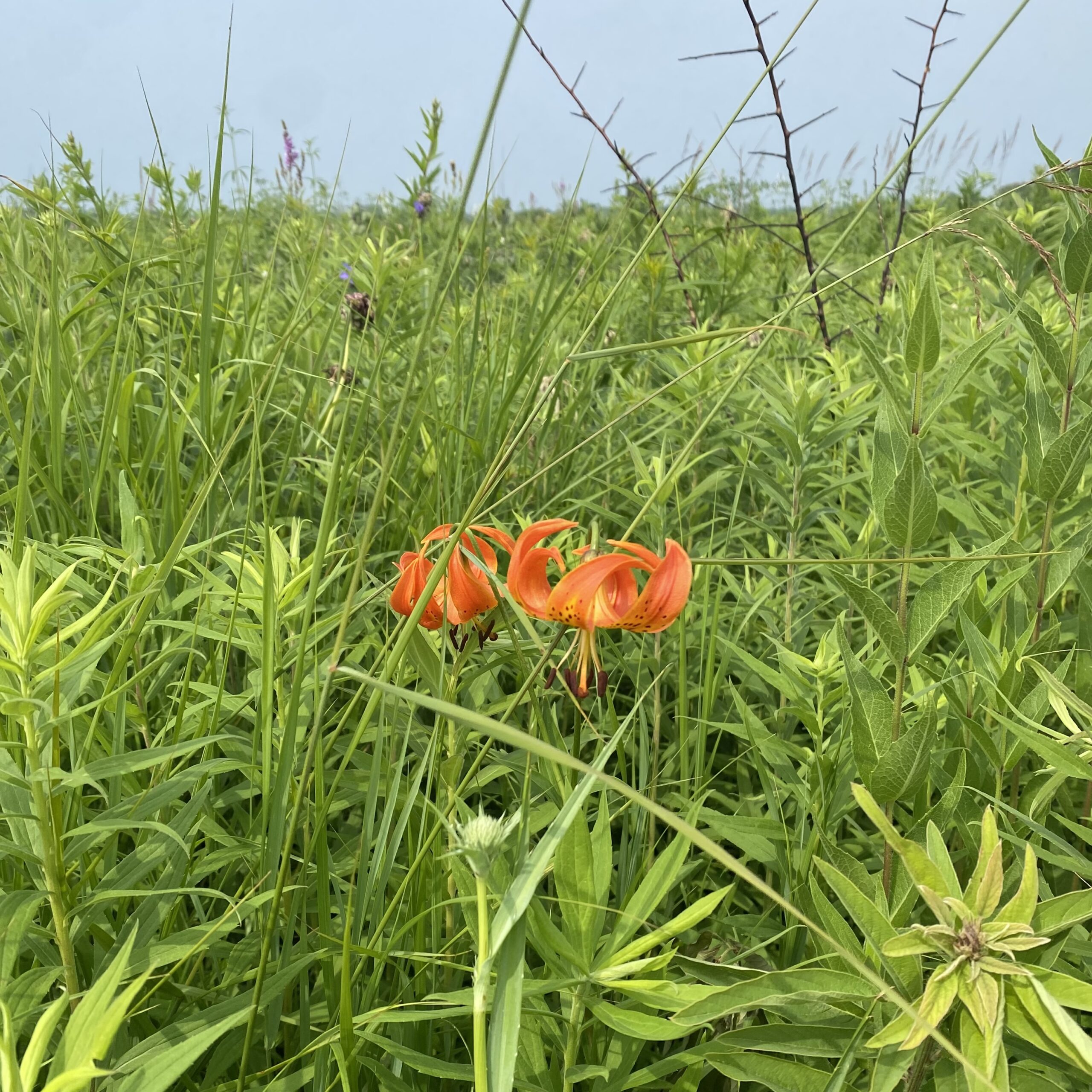

Over the first half of the season, we traveled throughout Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin visiting many federal parcels, as well as private and public partner lands, surveying target populations. We have seen Wet, Mesic, Dry, and Sand Praries, Oak Savannas, Woodlands, Wetlands and little bit of everything in between (Yay transition zones!). It has been a little challenging at times to find populations that are both remnant and large enough to sustainably collect from, but we have been successful in making 10 collections at this point in time. Some of my favorite plants that we have seen so far include those in the Orobanchaceae family, including the Wood Betony (Pedicularis canadensis), Downy Cup Paintbrush (Castilleja sessiflora), and Scarlet Paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea). We have even been able to return and collect from a few of these populations since these photos were taken!

With great regional travel, comes a great deal of meals on the road. This has led our “All Midwestern Crew” to branch out and try some of the most local delicacies as possible, some of which have been uncommon even to the most ope-ing, pop drinking, ranch devouring, over “thank you”-ing crew around. While slightly smaller than our target species list, it has been enjoyable growing our Midwest Regional Food List, regularly adding new, rare (and generally high caloric) Mid-American cuisine. Iowa has been special to me in particular, allowing me to try to find the top tenderloin in the region. While there may be many, some are better than others, and my go to for a top quality tenderloin is Goldies Ice Cream Shop in Prairie City. Not too far from the entrance to Neal Smith NWR, you head in for the Ice Cream, but will return for the Magg Special, a sandwich that combines a cheeseburger on top of the standard (extra crispy) tenderloin. Great food and also the best restaurant service that I have been offered since early 2020.

What would a Midwest food list be without food from the heart, good Ol Chicago. Our crew has been fortunate enough to have many Portillo’s and Museums within the general vicinity, allowing us to enrich both our bodies and minds with Italian Beefs, Hot Dogs and Art to our hearts content. There has also been a lot of talk about Chicago Style Deep Dish Pizza, which we are yet to sample as a crew, but true fans of Chicago Style Pizza know Tavern style is really where its at. Also hearing that some people do not consider Deep Dish a Pizza?! What is it then people! I will follow up on the CSP if we end up at the famed Pequods or somewhere off the radar.

Our next stop on our food tour of the Midwest was Minnesota. Land of many lakes, even more fish, and Minneapolis’ gift to human kind-Juicy Lucys! What a saucy stop we did indeed have over at the 5-8 Club just outside of Minneapolis. After a long day of replacing a stuck truck tire, changing out a rental car at the airport and 8 hours of interstate travel, we were quite content at the wonderfully delicious nature of the delightfully cheese filled Juicy Lucys and Saucy Sallys. Sometimes field meals hit harder than others, and this was definitely was one of those occasions. Another meal that swam above the rest was Deep Fried Walleye. There is nothing like some fresh fish out of the lake, and the Cormorant Pub in Pelican Rapids knows how to serve it up, no sauce needed! Minnesota was also gracious in providing us with the opportunity to witness the Showy Ladies Slipper (Cypripedium reginae), Greater Yellow Lady Slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens) and White Lady Slipper (Cypripedium candidum).

This past week we ended up visiting Wisconsin- the true land of American Style Cheese. While we opted for lighter faire during the first half of the trip (Chipotle), we indulged in true Wisconsinite fashion for the second, enjoying Curds that could stretch around your head three times, Mac and Cheese so rich it could pay back your student loans, and Potatoes au Gratin that made me question my allegiance to France.

Over the next few weeks we are slotted for trips to Northern Michigan and Southern Illinois. While there are plenty of new plants to survey, miles to drive, and tenderloins to taste, as a born and raised Michigander, I look forward to sampling the Pasties of the UP, debatably the original field food. Until next time, a l’aise Breizh!

Monarda in the Midwest

Wild bergamot, horsemint, beebalm, Monarda spp… a genus that has stolen my heart!

Apparently it’s berga-MOT, not berga-MONT as I always have thought, and it’s not the source of the well-known essential oil of bergamot, which comes from the fruit native to Italy. However, this aromatic, herbaceous perennial of the mint family (Lamiaceae), has a scent similar to that of Citrus bergamia, and has many edible and medicinal properties.

I first saw M. fistulosa in the prairies of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. I love the pale magenta tubular flowers, sticking up like a tuft of troll hair, and the buds that look like little presents, all folded up. White flowers were also found among the magenta, which in some cases may actually be M. clinopodia, but I’m not sure.

There are about 18 Monarda species in the world (Elpel), and about 7 native to Illinois including M. bradburiana; M. clinopodia or white bergamont; M. didyma or scarlet beebalm; M. fistulosa of which 3 varieties have been found in IL, including M. fistulosa var. rubra which is deep purple to crimson; 2 varieties of M. punctata, spotted beebalm; and M. media, a rare reputed hybrid between M. fistulosa and M. clinopodia (Mohlenbrock). The differences are minute, and I will have to practice my keying skills!

Monarda is one of the few native herbaceous plants I’ve seen in the urban neighborhoods of Chicago where I live. The other week I spotted a somewhat rare strip of prairie plants in a park strip in Wicker Park neighborhood (Hoyne Ave and North Ave).

At Chicago Botanic Garden, you can find a cultivated hybrid varieties developed by Proven Winners named Upscale TM in the Lavin Evaluation Garden. Pictured below are the ‘Red Velvet’ variety. They are much taller than the ones I’ve seen in the wild thus far.

Suggested Reading:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/monarda_didyma.shtml

https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_mofi.pdf

Citations

Elpel, Thomas J. (2021). Botany in a Day: The Patterns Method of Plant Identification, An Herbal Field Guide to Plant Families of North America (6th ed.). Hops Press.

Mohlenbrock, Robert H. (2002). Vascular Flora of Illinois. Southern Illinois University Press.

Pick the Berries

What’s my favorite part of seed collecting and weed treating?

The berry picking.

During my time here in the Umpqua, I have successfully established myself as “the berry girl” to those that I work with most frequently.

Wild strawberries, thimbleberries, and blackberries have become a part of my daily diet. Not intentionally or by planning. They just so happen to be growing wherever we are in the Forest – like little presents presented to me throughout the workday.

Collect a seed, eat a berry. Pull a weed, eat a berry.

Whenever I first arrived in Oregon in late May, the berries were not ripe enough to eat, perhaps just barely formed or not at all. To my delight, however, June brought growth and development – for the plants and myself.

Like the briars of the wild, native blackberry, moving away from home can sting – bringing about uncomfortable, newfound independence and solitude. The only way to avoid getting scratched is by not picking the berries.

But also like the berry, moving has been and can be incredibly sweet and satisfying. So I say, pick the berries! experience life. move to a new place. start a new job. meet new people.

Berry picking is a toss-up. Regardless of how well you think you’ve selected your seemingly ripe fruit, sometimes you still end up with a rather tart or bland taste or even a few bugs … Thankfully, I can say that the Umpqua has been exactly what I wanted and so far, the sweetest of picks.

I do think that I will be quite sad when berry season is over. Maybe that is why I have an ode to blueberries on my arm – a tattoo to commiserate my time in Maine last summer where wild blueberries grew like grass in fields around Acadia National Park.

Thinking back, I do suppose that I find berries wherever I go, like hallmarks of my summers and travels.

So I make the time to find the best berry patches after work and on the weekends. I enjoy their existence while there is still time because seasons don’t wait for us. We live according to the seasons and whether or not we experience them to the fullest is on us.

So I pick while I can and I live while I can – enjoying the briars and the berries that I find along the way.

-CM

Prickly Predicaments

My first month working at the San Bernardino National Forest has been so much fun! After participating in a lot of amazing projects, we were finally able to start making some seed collections at the end of the month.

Don’t Hug A Yucca

Interior goldenbush (Ericameria linearfolia) was one of our first contenders for seed collection. Big Bear has had an especially wet year, so even though these guys were among the first on our list for collection, they actually went to seed a bit later in the season than usual.

On the day we showed up for collection, there were seeding Ericameria linearifolia as far as the eye could see. It was any new seed collector’s dream! I set out with my labeled bag and started collecting. After about half an hour of collecting from various smaller plants, I saw the perfect goldenbush. It was huge and every flower was seeding with very little seed dispersed! I knew I was going to be at this one for a while, so I crouched down beside it and then…

I literally sat on a yucca! It hurt so bad and started bleeding a bit immediately, but luckily the pain went away pretty quickly and I continued seed collecting. Regardless, contrary to what the sticker at our Regional Botanist’s desk might say, fellow seed collectors, don’t “Hug a Yucca”!

Thistle Be Interesting

At the same site, I helped Koby, a Biological Restoration Technician, with the collection of some native cobweb thistle (Cirsium occidentale). This plant species isn’t on our CLM seed collection list, but it’s on the general SBNF seed collection list and its elusive nature intrigued me.

See this thistle has what I’d refer to as a close evil invasive twin… Cirsium vulgare. Even the name sounds like bad news! Seeing them side by side in the pictures above, the differences are pretty clear. But in the field, when you’re worried about accidentally collecting from an invasive and looking at just one of the species on their own, the differences seem less apparent. During my first week on the job, I learned that several forestry techs at our office were wary of collecting from our native cobweb thistle and reluctant to pull bull thistle for fear of choosing the wrong Cirsium.

Since then, I took a special interest in telling these twins apart. I learned that bull thistle tends to look meaner, greener, and the leaf tips extend in a way that looks like it’s giving you the finger for just looking at it. Vulgare indeed… I also learned that bull thistle tends to like moister soils near water while cobweb thistle prefers well drained soils. Our native cobweb thistle also has dark seeds and the leaves are generally more narrow, sage green, and overall just look like they’re adapted to a drier climate. Having conversations about the differences between these two thistle has given a lot of us at the office more confidence around telling these two apart. I was so pleased to hear one of my coworkers come up to me the other day with a HUGE bag of thistle seed and proudly say “I’m not afraid of thistle anymore!”. Ana Karina and I are hoping to collect vouchers of these two thistles so they can be displayed side by side and help future SBNF employees and interns!

The Ants Beat Us To It!

Finally, we also collected Stipa speciosa (Desert needle grass). We learned that the tail on Stipa seeds bend to a right angle when the seeds are fully matured. What I was truly fascinated by, though, was finding this grass bunch where ants were harvesting seed! They were slowly pulling the seeds out and we saw a trail of ants hauling seeds back to the ant hill. I recently learned that some plants have a special relationship with ants in which ants will take the seeds with them underground effectively planting the seeds and allowing the plants to grow. Who knew ants were seed collectors and gardeners too!

I’m so excited to continue learning about our California natives and being a part of some great projects in the month of July. Also, we will finally be getting our own tablets!! I hope everyone is having as much fun as I’ve been having and I’m so glad to be a part of such a great program!

The beginning…

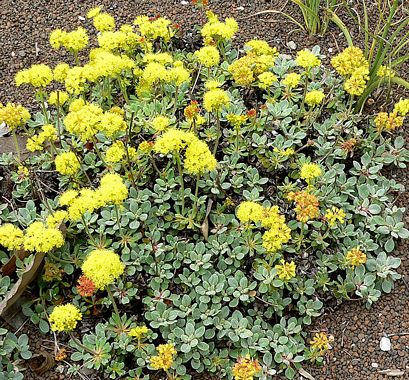

The first month of this internship has been adventure at every turn. We started with helping the forest service technicians with common garden experiments. We have been studying how certain plants are growing, and the amount of herbivory that is present on them. We have taken breaks to look for Lomatium dissectum and Eriogonum umbellatum.

LODI

ERUM

It has been fun hunting for our target species, and we were able to find some LODI and ERUM up at Bogus Basin, but there were not enough seeds to harvest. All life was going well until things got a bit crazy. We went to Modoc Plateau to get tissue samples of various target species from a range of different wetland sites. We were cruising along, making good progress and driving through some pretty intense backcountry roads. It was day 3 of our trip, when we were not careful enough and ended up getting stuck in a huge mud bog! It took us a day to be rescued, and even then we had to work together to pull the truck out of the mud. It took a ford F-250 to help pull a ford F-150 (Mountain goat).

All in all it was a great bonding experience, and a memory I will never forget. You live and you learn!

Home Sweet Home

Headed northbound on I-55, I found myself surrounded by fields of familiar Illinois flora: Zea mays and Glycine max, better-known by their common names “corn” and “soybeans.”

Upon my return home from college, however, I now also eyed scattered blooms of Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica), Wild Hyacinth (Camassia scilloides), and Shooting Stars (Dodecatheon meadia) in preparation for the next six months spent at Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie.

Formed by glacial outburst floods during the Ice Age, Midewin and the surrounding areas host some of Illinois’ last remaining dolomite prairies. Numerous rare plant species call this habitat home, spared from the plow due to its characteristically thin soils.

This unique plant community has presented the opportunity to work alongside the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Plant of Concern program, monitoring sub-populations of Small White Lady’s Slipper (Cypripedium candidum), Slender Sandwort (Minuartia patula), Butler’s Quillwort (Isoëtes butleri), and Buffalo Clover (Trifolium reflexum).

Many weeks have already been spent stumbling through sedge-meadows and honing my plant identification skills — much needed for the intimidating amount of Carex on our Target Species List.

Other days have been used to put my CLM training to the test, collecting seed from Yellow Stargrass (Hypoxis hirsuta), Blue-Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium albidum), and Prairie Violet (Viola pedatifida) from a patch of remnant prairie at Lobelia Meadows.

Despite being raised less than 10 miles away from Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, I’ve already explored it more this past month than I have my entire life.

And although it’s no Chugach or Tongass National Forest, Midewin is nevertheless a gem of the Prairie State — no matter how many acres of corn and soybeans hide it.

Dade Bradley

Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie

Month #1 in Beaverhead County

Days and weeks out here are flying by!

We were busy our first week with white bark pine surveys in some amazing locations along the Continental Divide trail. These missions were not related to seed collection, but really helped me acclimate to the new ecosystem as a whole. I am working on the only botany crew in Beaverhead-Deerlodge NF (consists of six botanists, including myself), so we are tasked with covering as much of the 3.3 million acre forest as possible.

We quickly moved on to rare plant monitoring by checking up on known populations of Physaria pulchella, Penstemon lemhiensis and Primula alcalina. These plants were each super specialized to particular environments, so it was super interesting vising and identifying different habitat types.

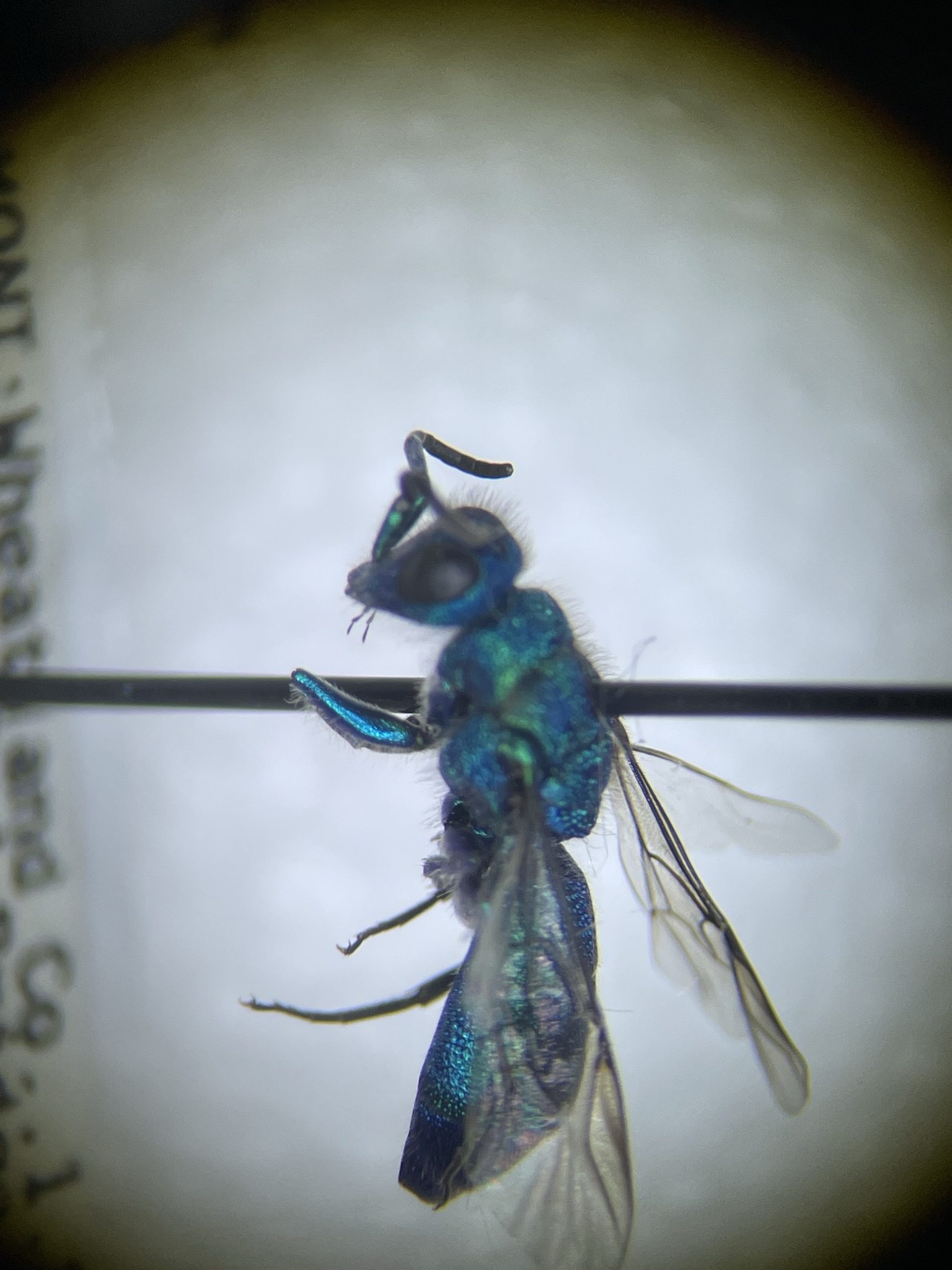

Next we begun collecting bees for a pollinator survey which resulted from a partnership between Montana State University and the Forest service. These surveys were really unique and required us to run around in meadows of wildflowers with children’s butterfly nets to catch pollinators. We stayed onsite for a week, pinning the bees to preserve them at the campsite each night. This culminated in a visit to MSU’s pollinator research lab to see the archival process.

Ten-hour days in the field are sometimes long, but I’ve been having a great time at work. I feel like an honorary member of the FS botany crew and am making sure to explore on my free time. I feel super grateful that I am able to work in such an interesting place with such likeminded people.

Some quick bits about my adventures outside of work:

-Spontaneously rode in a 67-mile bike race through the Pioneer Mountains on 1 day notice.

-Met up with some fellow CBG interns at the Bozeman hot springs for a grass ID event.

-Our urban test garden is growing quick down in Lawndale, IL, so check it out if you happen to be in the area (lots of strange weeds to ID)

-Went to my first demolition derby

-Had a good time at the Twin Bridges Bluegrass Festival

-Got some great wildlife pictures and they will be ready to share by the next blog post

New Place, New Plants, New Possibilities

As someone who has lived most of their life below an elevation of 3500 ft on the east coast, moving to the west for the summer and staying mostly around the 6000-7000 ft elevation range has been a great adventure. All of the wildlife is vastly different from what I am used to and I was lucky enough to see my first moose on my first day in Montana. Since then I have seen many new animals in person including elk, antelope, ground squirrels, marmots, snowshoe hares, new snakes, and my new favorite birds – magpies. I am also excited and apprehensive about the other new, larger animals that are more common here compared to home – grizzly bears and mountain lions – but have yet to run into them.

Along with many new animals that I had not seen before, I am also excited to see and learn of lots of new plants that I had not previously known as well! Some of my favorites so far include all of the species of Phacelia (Scorpionweed), Penstemon (Beardtongues), and Mertensia (Bluebells) which I had not seen in my home state of North Carolina. And I am definitely looking forward to trying some huckleberries for the first time whenever they are in season! There are also some new species within genuses I already was familiar with such as Actaea rubra, Acer glabrum, and many new pines and spruces. The mountains in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest as well as the ones I am used to from North Carolina are both very beautiful and yet so different from each other. Montana has way fewer broadleaf trees than what I am used to and I am looking forward to learning all of the conifers that make up the amazing forest that I am working with this summer.

Already I have gained many new skills and experiences and I can not wait to see what the rest of the summer brings to me from this wonderful opportunity and I am so excited to help contribute to future restoration projects in order to keep these forests thriving!

Greetings from the UKB!

When I received my offer letter from Chicago Botanic Gardens to work with U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in Klamath Falls, OR, I was beyond enthralled! Coming from Omaha, NE, I had never experienced a landscape quite like southern Oregon. Knowing I was going to have an whole summer dedicated to studying an entirely new range of species was my sole motivator for making the twenty-two hour trek out here.

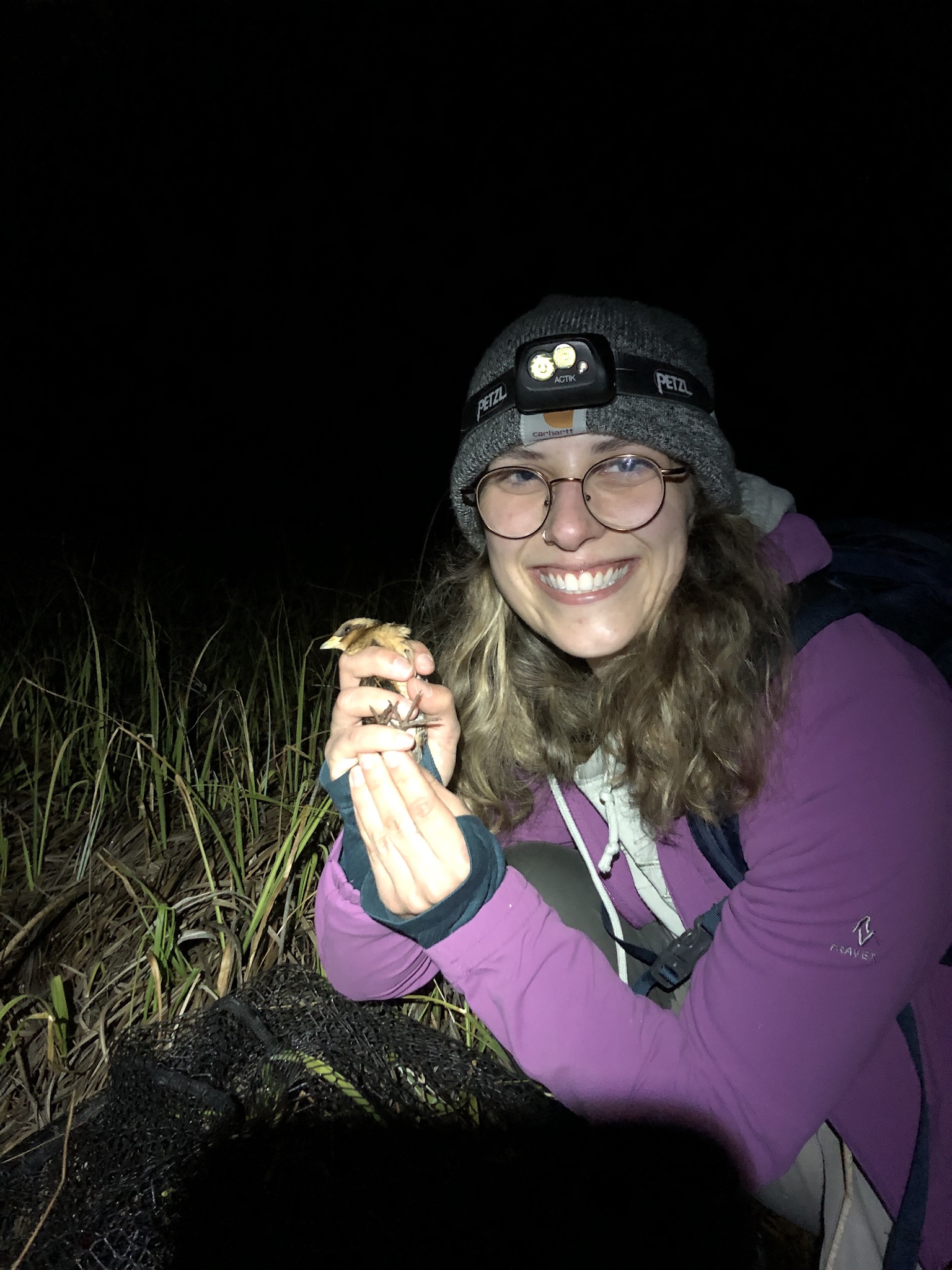

My first project started the week of May 8th, where another intern, Loretta, and I, had the opportunity to conduct yellow rail (Coturnicops noveboracensis) surveys within the Klamath Marsh. These small birds, only a few inches in length, reside in grassy marshes and due to their brown and yellow coloration, are difficult to see from the naked eye. Due to the decline in population, rail surveys are important indicators of the health of the marsh. In order to attract yellow rails, we had to create a series of clicking noises with stones (a technique that was difficult to perfect) which lured male rails toward our net. After they were trapped, we carefully handled the bird using a bander’s grip, shown below.

We then placed a silver band around their leg, measured the length of each bird’s wing, tail, tarsus, and culmen. In the end, we surveyed 30 birds throughout the course of three nights. It was a rewarding first project that I was grateful to be a part of!

After a week of rail banding, I spent the remainder of May working with the FWS hatchery crew. The hatchery’s main focus is to restore lost river and shortnose sucker (Deltistes luxatus and Chasmistes brevirostris) populations within Upper Klamath Lake. Larvae from both populations are collected at the mouth of the Williamson River, which feeds into Upper Klamath Lake. The larvae are then brought back to the hatchery and, upon successful survival, will be released once they have matured.

A bulk of our summer has consisted of monitoring bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) populations at Deming Creek and removing brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) populations from Callaghan Creek. Bull trout populations have significantly declined from habitat loss and degradation, which is why they are listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Brook trout are an invasive species throughout the Upper Klamath Basin (UKB) because they are out-competing bull trout for vital resources. In order to restore the health of waterways, brook trout removal and bull trout re-introduction must be conducted.

Species monitoring and removal are completed with backpack electroshockers, which are designed to temporarily shock the fish while mitigating harm. For bull trout monitoring, electrofishing gives us the ability to easily record measurements and other useful data that indicates the health of the fish. Below is a picture of a healthy brook trout found at Deming Creek.

Aside from species’ monitoring, electrofishing allows us to capture and remove as many brook trout as possible. At first, I was quite uncomfortable with removing up to 300 brook trout a day, however, I have begun to recognize the importance of invasive species removal.

Outside of fieldwork, I have been able to connect with several employees at the Klamath Falls office, all who have been extremely helpful in providing me with ample resources. I am beyond appreciative to be an active participant in the conservation work being performed within the Upper Klamath Basin and I cannot wait to share more updates about my time with FWS!

Maddie Weinrich