My first month working at the San Bernardino National Forest has been so much fun! After participating in a lot of amazing projects, we were finally able to start making some seed collections at the end of the month.

Don’t Hug A Yucca

Interior goldenbush (Ericameria linearfolia) was one of our first contenders for seed collection. Big Bear has had an especially wet year, so even though these guys were among the first on our list for collection, they actually went to seed a bit later in the season than usual.

On the day we showed up for collection, there were seeding Ericameria linearifolia as far as the eye could see. It was any new seed collector’s dream! I set out with my labeled bag and started collecting. After about half an hour of collecting from various smaller plants, I saw the perfect goldenbush. It was huge and every flower was seeding with very little seed dispersed! I knew I was going to be at this one for a while, so I crouched down beside it and then…

I literally sat on a yucca! It hurt so bad and started bleeding a bit immediately, but luckily the pain went away pretty quickly and I continued seed collecting. Regardless, contrary to what the sticker at our Regional Botanist’s desk might say, fellow seed collectors, don’t “Hug a Yucca”!

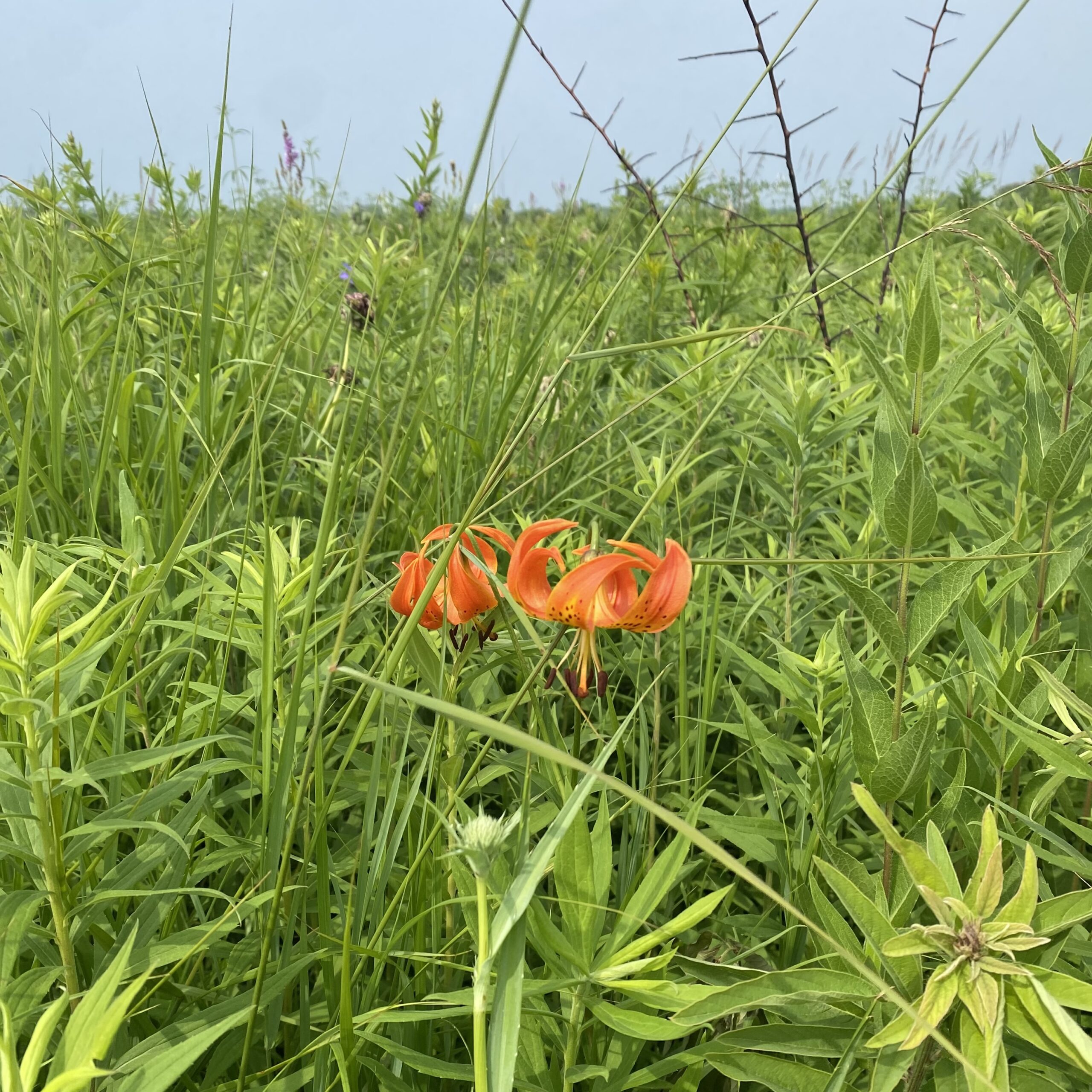

Thistle Be Interesting

At the same site, I helped Koby, a Biological Restoration Technician, with the collection of some native cobweb thistle (Cirsium occidentale). This plant species isn’t on our CLM seed collection list, but it’s on the general SBNF seed collection list and its elusive nature intrigued me.

See this thistle has what I’d refer to as a close evil invasive twin… Cirsium vulgare. Even the name sounds like bad news! Seeing them side by side in the pictures above, the differences are pretty clear. But in the field, when you’re worried about accidentally collecting from an invasive and looking at just one of the species on their own, the differences seem less apparent. During my first week on the job, I learned that several forestry techs at our office were wary of collecting from our native cobweb thistle and reluctant to pull bull thistle for fear of choosing the wrong Cirsium.

Since then, I took a special interest in telling these twins apart. I learned that bull thistle tends to look meaner, greener, and the leaf tips extend in a way that looks like it’s giving you the finger for just looking at it. Vulgare indeed… I also learned that bull thistle tends to like moister soils near water while cobweb thistle prefers well drained soils. Our native cobweb thistle also has dark seeds and the leaves are generally more narrow, sage green, and overall just look like they’re adapted to a drier climate. Having conversations about the differences between these two thistle has given a lot of us at the office more confidence around telling these two apart. I was so pleased to hear one of my coworkers come up to me the other day with a HUGE bag of thistle seed and proudly say “I’m not afraid of thistle anymore!”. Ana Karina and I are hoping to collect vouchers of these two thistles so they can be displayed side by side and help future SBNF employees and interns!

The Ants Beat Us To It!

Finally, we also collected Stipa speciosa (Desert needle grass). We learned that the tail on Stipa seeds bend to a right angle when the seeds are fully matured. What I was truly fascinated by, though, was finding this grass bunch where ants were harvesting seed! They were slowly pulling the seeds out and we saw a trail of ants hauling seeds back to the ant hill. I recently learned that some plants have a special relationship with ants in which ants will take the seeds with them underground effectively planting the seeds and allowing the plants to grow. Who knew ants were seed collectors and gardeners too!

I’m so excited to continue learning about our California natives and being a part of some great projects in the month of July. Also, we will finally be getting our own tablets!! I hope everyone is having as much fun as I’ve been having and I’m so glad to be a part of such a great program!