We could hear the river before we could see it, a steady rush of water cascading in the distance. Then, in an instant, the forest opened into light as my co-intern Tessa and I found ourselves on the river bank. More accurately, we found ourselves above the river bank. A steep 10 foot drop separated us from the sprawling shore below. After a moment of contemplation, we slid down the slope, our backs covered in red earth.

Once we were on the bank, it took only a few moments to find one of two plants we had come looking for. Spread across the shore was a milk vetch, native to the region and rare in Michigan. The milk vetch was in full flower, its long white blooms tinted with green at the base and purple at the tip.

A moment later, we spotted the second plant we were searching for, an invasive sweet clover. Like the milk vetch it was in full bloom. The plant’s tall stems were sporting tiny white flowers, each with the potential to turn out seeds and create another generation to spread along the shore. I couldn’t help but admire the plant’s beauty as I pulled it.

Milk vetch and sweet clover are distant cousins, both members of the legume family, but where invasive sweet clover thrives along Michigan’s roadsides and shores, native milk vetch is scarce. As we walked along this river, though, the opposite seemed to be true. The milk vetch flourished. Not taking over by any measure, but coexisting well with the other species and easy to spot all along the bank. The same wasn’t true for the sweet clover. We found only two stems. Perhaps the hard work of interns before us has payed off. The clover, which forms thick clusters along other shores, has had no success in crowding out the milk vetch.

For almost two months now, I’ve been working on projects like this, helping manage invasive species in Ottawa National Forest. Over the weeks, I’ve begun to fall into a routine. Tessa and I arrive at the office at dawn and meet with our mentor, Ian, to discuss the day’s plans. Then, we load up the truck and head out into the field, driving from site to site to monitor, map, and manage the Ottawa’s many invasive plants.

Summer is in full swing in the forest. When I first arrived, the last trees were just beginning to leaf out and the honey suckle we treated had dense clusters of yellow, white, and pink flowers. Now, the very first trees are tinged with orange and honey suckle is easy to identify with round, red and orange berries that catch the sunlight. As summer advances, the raspberry bushes which once bore only thorns are heavy with berries, wild ramps flower, and hazelnut trees tempt squirrels with their ripening fruits. Waking up every morning, I see the orange sun hanging heavy over the hills. In a few weeks, it will still be dark when I leave for work.

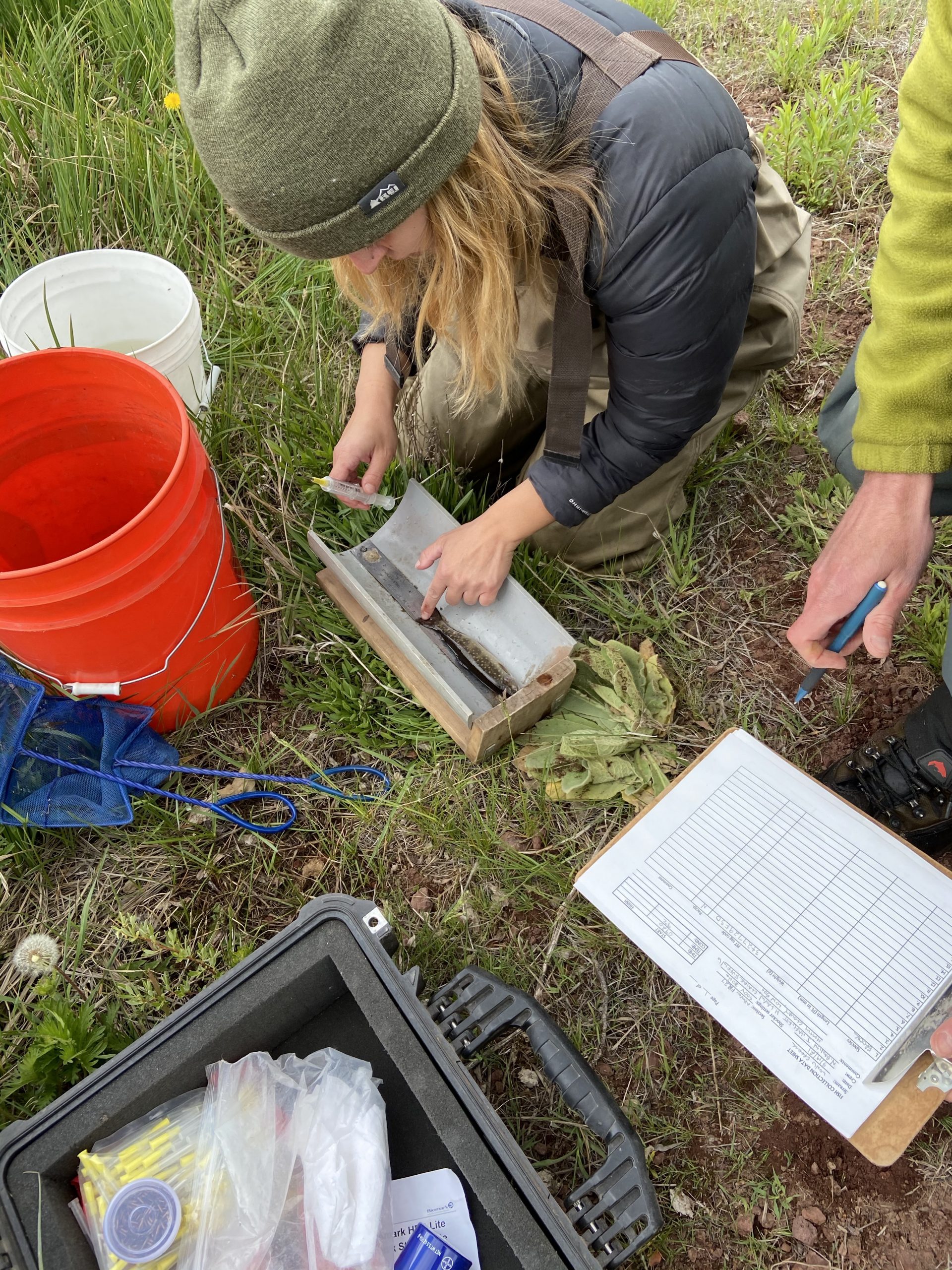

This week, we met with some of the forest’s Wildlife Technicians along with members of the Iron Baraga Conservation District for what Ian deemed “turtle day”. He explained to us that the Ottawa is one of the last strongholds of the endangered wood turtle. A herpetologist visited all of the Ottawa’s turtle nesting beaches and made recommendations for how we could make them better habitat for the turtles. It would be our job to turn those recommendations into reality.

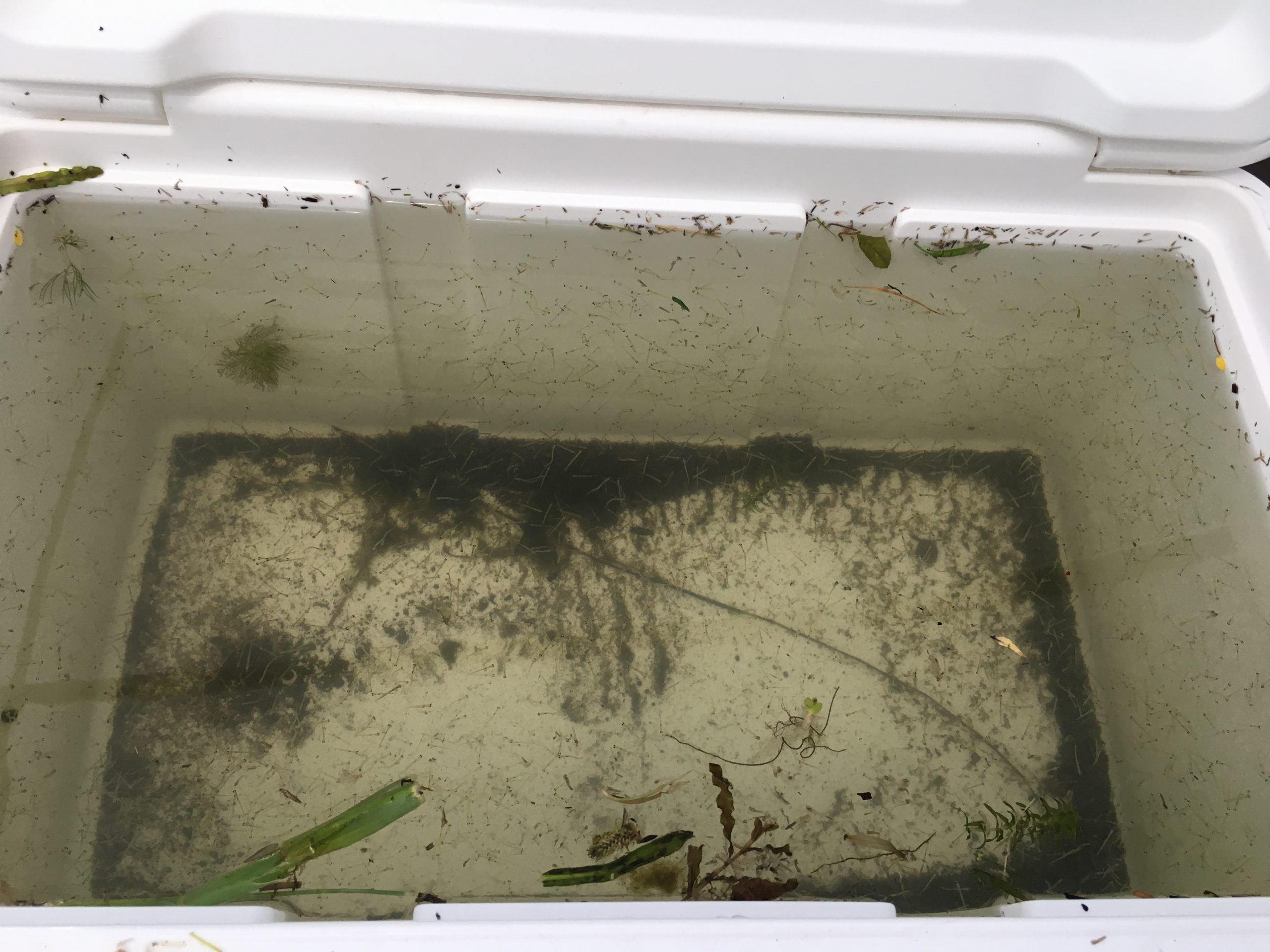

It turns out it’s hard to be a turtle. Busy roads, human poaching, and predators that eat their eggs are all major threats to the shy reptiles. To protect them from highways, conservationists erect knee-high turtle fences around the shore to keep them from wandering up to the roadside. To discourage poaching, the locations of the turtle beaches are shared only on a need-to-know basis. Slowing predation is difficult, but one thing that helps is making sure the sandy beaches where the turtles like to bury their eggs have the right amount of vegetation. Too much vegaition can serve as a physical barrier to the turtles and keep the eggs too shaded and cool, but too little vegetation means the turtles have nowhere to hide from predators. That’s where we came in.

Working together we spent all day treating invasive species and cutting brush to expose new sandy areas where turtles can lay eggs next year. Hopefully, the new habitat will also give turtles alternatives to burying their eggs on roadsides where they’re vulnerable to ever-rushing traffic.

As I drove home after a long day in the field, I began reflecting on our efforts. Even though we worked all day to create better habitat for turtles, we didn’t see a single one. For us, protecting turtles didn’t mean interacting with turtles, it meant managing the plants growing along the shore. For others, it could mean controlling predators that eat eggs, or working with people to educate them about avoiding turtle habitat and driving cautiously. Because species don’t exist in isolation, conservation efforts seldom focus on just the target species. To encourage the milk vetch, we pulled clover. To support the turtles, we cut brush and dug up tansy. Everything in the forest is in relationship.

Humans are a part of that, planting trees, building paths, harvesting timber. It’s easy to think of ourselves as separate, but working in the forest has shown me that’s not as true as I thought.

As I engage with forest management in a hands-on way for the first time, I’ve begun thinking about questions many conservation-minded people before me have asked: What is the nature of the various relationships between humans and the environment? What should those relationships look like to create a healthy, sustainable world? What steps can we take to get there?

Ian lent me the book, Rambunctious Garden by Emma Marris. It explores different conservation frameworks from all over the world and investigates the dilemmas I see every day as as we prioritize projects in the forest. I’m only a few chapters in, and it’s already informing the way I think about the relationship between people and the environments we shape. For me, creative turtle conservation methods became an invitation to think about a whole lot more.

Yesterday was full of glossy buckthorn. The towering bushes have shiny leaves that glint in the sunlight. We knew about a large infestation of the invasive species along the highway, stretching on both sides of the river. On a hunch, we continued walking past the known infestation. Every time we thought of turning back, we found another plant. Marking them as we went, the buckthorn seemed endless. Still, we treated the bushes and continued on diligently. Finally, as we made our way back to the truck, Ian stopped suddenly. There before us was a plant I now recognized. Brimming with white flowers was the rare milk vetch.

This was a new milk vetch site, never before recorded in the state. Once we started looking we found several more clusters of milk vetch along the highway. We scrambled to document the population, taking pictures and recording the nearby species. The experience was what I imagine it would be like to go to Starbucks and see a celebrity ordering coffee.

Milk vetch can grow well along bright riversides, but we quickly realized the river was hundreds of feet away. Ian thought that perhaps, with workers cutting the tallest plants to maintain the right of way, the milk vetch was able to find a home in the sunlight of the roadside ditch. Looking at the flowers as cars rushed by, I couldn’t help thinking about how complicated conservation is. Humans have drastically shaped the roadside environment. This has given glossy buckthorn the opportunity to run wild. At the same time, milk vetch has been able to find one more foothold in Michigan.

It seems most management decisions come with benefits and drawbacks alike. Thinking about it, I’m grateful for all the researchers who are working hard to help us understand the many rippling effects of our interactions with the environment and all of the people, beginning in Michigan with Indigenous communities, who have worked hard to manage the land responsibly. Conservation and management are complicated tasks, but they become a little easier, I think, when we recognize our role as one more species, living in relationship in an interdependent world.