I’ve been helping the Midewin hydrologist (technically the fish biologist) Len Kring compile the Watershed Restoration Action Plan (WRAP), and in the process, learning many things that my basic (eco)hydrology course at NU had not taught me. Let me begin with an analogy — water is a hungry creature. It eats sediment when it is pure, and only once it becomes satisfied on a good meal of sand, clay, and silt, does it contently meander its way downstream, lazily picking up some sediment in one place and depositing a little in another. When something rudely interrupts the water’s course and forces the water to drop its sediment, it once again becomes hungry and begins eating away at the banks and bed downstream.

Unfortunately, there are many things that bother the water of Prairie Creek as it flows through Midewin, which encompasses about 80% of the Prairie Creek HUC 12 watershed. There are old bridges with supports in the middle of the creek. I thought at first, what could possibly go wrong with supports in the creek? But one only needs to take one look at the old railroad trestle with at least 3 supports in the river that has accumulated an impressive log jam behind it to see the problem. As debris floats down the stream during high flow, it gets caught in those supports, accumulating and forming a dam. This not only prevents fish and other aquatic organisms from traveling across the barrier, but it also causes the areas downstream of the dam to erode heavily. This is because obstacles cause sediment previously carried by the steam to be deposited, meaning that the water immediately downstream of such obstacles is relatively free of particulate matter and “hungry”, wanting to pick up sediment from the banks and channel bed. Water also tries to go around the dam, widening the channel at both ends, until those alternate paths also get blocked by incoming logs. In the end, the downstream portion becomes both wider and deeper, and the banks keep receding. The solution is to demolish all unneeded legacy bridges, and replace those that are still necessary with bridges having no in-stream supports.

A similar issue occurs on a smaller scale with poorly designed culverts. These are typically under roads, and often take the form of two or three buried pipes. Typically, they are too narrow, causing water to flow through them at higher velocities than it normally would, causing erosion on the downstream end. While the culvert begins with having the same level relative to the ground on both the upstream and downstream sides, it often ends up being above grade on the DS side, resulting in a waterfall. Additionally, these small culverts also often become blocked with debris, causing water to erode the soil around the culverts as it seeks a new path through. This has resulted in numerous culverts developing large potholes, making the roads above them almost impassable. The solution is creating wider culverts consisting of bottomless arches sitting on bedrock or a concrete slab.

Worst of all, there is a large dam just north of Doyle Rd., which is significantly altering channel shape and function both upstream and downstream, and acts as an impenetrable barrier to fish and other aquatic organisms. Removing the dam might be as simple as dynamiting it and then carting away the debris. However, there is a large amount of sediment trapped behind the dam (reaching almost the top of the dam on the upstream side), which may be contaminated due to army activities. This means that before the dam is removed, the sediment must be tested for contamination. If there is a hazardous level of contaminants, the sediment would need to be dredged out from behind the dam before the dam can be removed (as removing the dam would mobilize all of that sediment). This would significantly complicate the process and drive up costs.

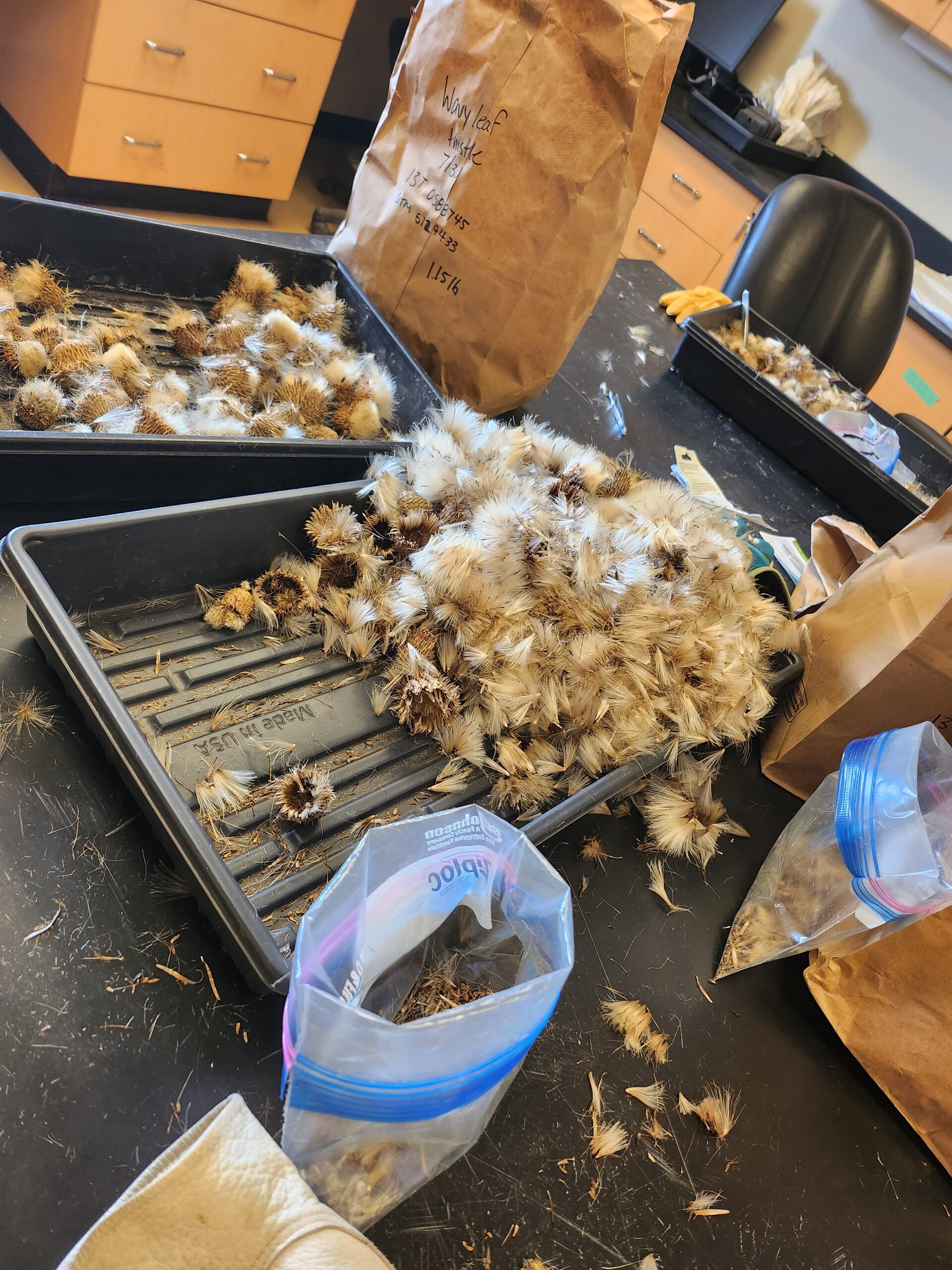

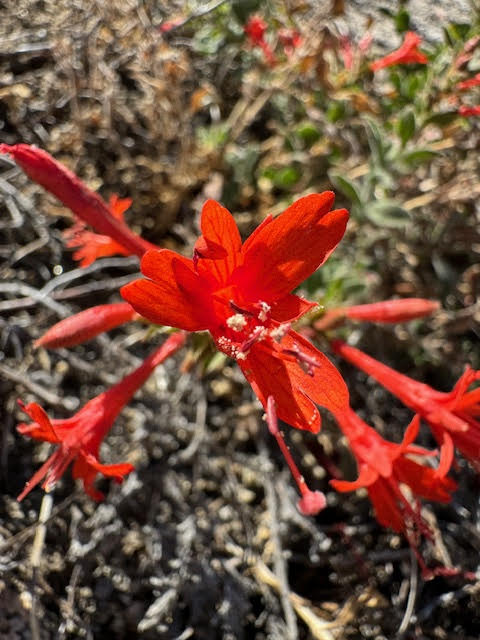

The Watershed Restoration Action Plan (WRAP) for Prairie Creek includes all of these things and much more. The plan lists all steps (essential projects) that are necessary in order to improve the watershed to the next condition class, the three classes being (3) impaired function, (2) functioning at risk, and (1) functioning properly. In the case of Prairie Creek, the current state is functioning at risk and the desired state is functioning properly. Most importantly, approval of this plan will allow Midewin to acquire funding to address the essential projects, which include both structural improvements like ones listed above as well as invasive species removal and native habitat restoration throughout the watershed.