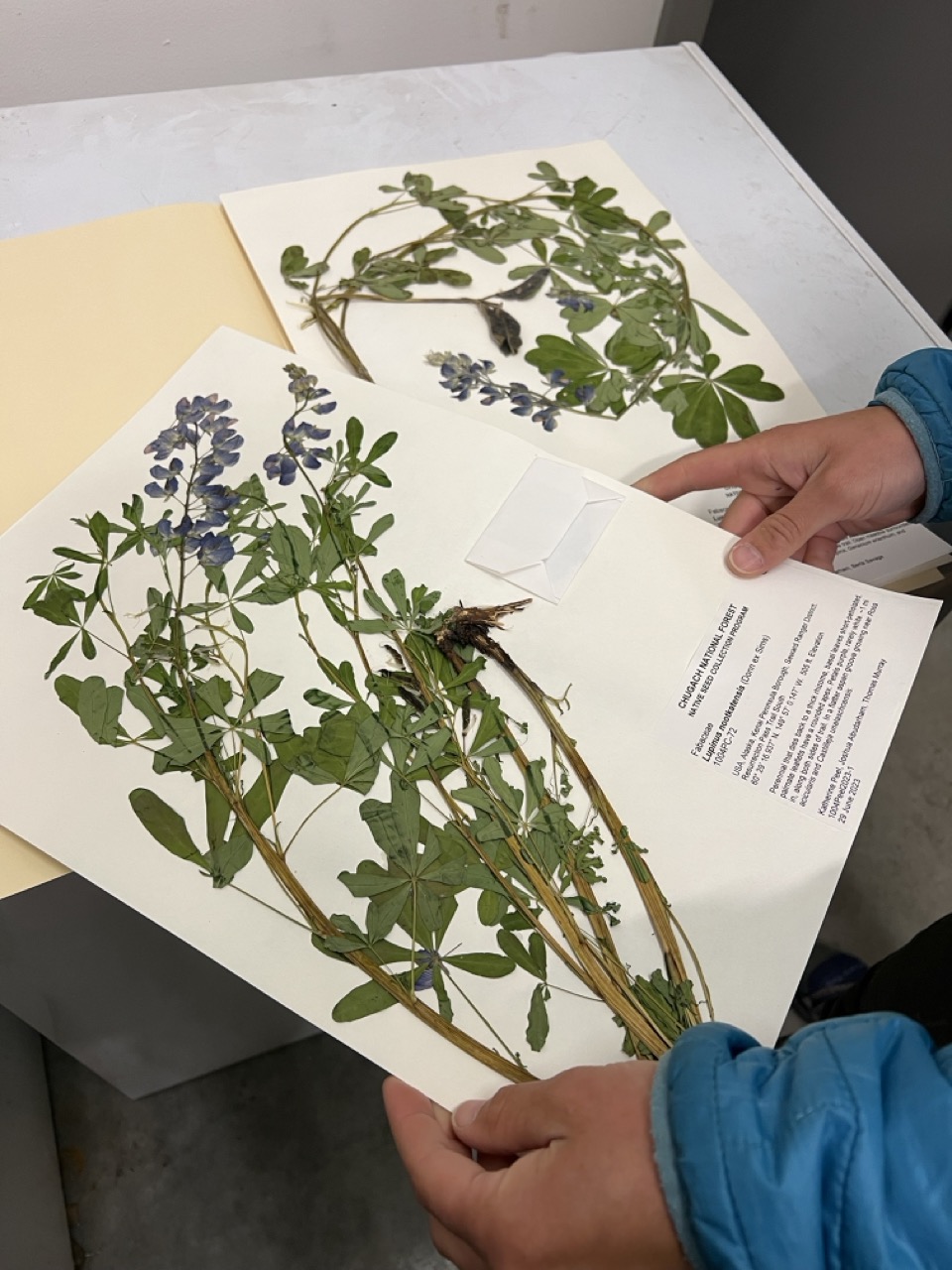

Plants shape our historical and modern worlds

For many of us in the modern age, plants blend into the background. The joy of this internship, and other outdoor work, is the movement of plants to centerstage again as primary shapers of the world. Not long ago in Europe and much more recently in North America, plants were the primary suppliers of medicine and raw materials. Here in and around the Flathead National Forest, plants were imperative for everyday life of the Salish and Kootenai people. An exhaustive list of plants and their traditional uses is not possible here, but important edible plants included Serviceberry, Huckleberry, and Camas (Bear Don’t Walk, 2019). Plants for raw materials included Apocynum cannabinum for rope, Salix (willow) for fish traps, and Holodiscus discolor (oceanspray) for digging stick handles (Ryan, 2024). In the paragraphs to follow, I focus on three medicinal plants, common and widespread across multiple continents, that many cultures used and still use today. The independent use of these plants for similar ailments across different cultures corroborates their effectiveness. The application of these plants goes back thousands of years, with the origin of their medicinal value shrouded in myth and legend but their effectiveness indisputable and tangible with the modern-day scientific isolation of their bioactive compounds.

Yarrow: ancient medical hero

Yarrow, the common name for various plant species in the Achillea genus, is widespread throughout Eurasia and North America. Species of Achillea have been used for thousands of years in the treatment of wounds, infections, inflammation and skin conditions (Applequist & Moerman, 2011). Yarrow pollen was unearthed at the 65,000-year-old burial site of several Homo neanderthalensis in a cave near Shanidar, Iran (Applequist & Moerman, 2011). The genus name, Achillea, honors the ancient Greek mythological hero Achilles. Achilles was not just a famed (nearly invincible) warrior; he was also trained in the arts of medicine by his tutor, Chiron the Centaur. The ancient Greeks believed Achilles discovered the astringent properties of Yarrow and carried it with his army to stem bleeding wounds (Chandler et al.,1982). In addition to wound healing, the Salish boiled leaves and stems of Achillea millefolium for colds and made a compress out of the leaves for toothaches (Hart,1979).

Modern-day chemical analysis and assays of the bioactive compounds in Achillea reinforce traditional medicinal uses. Sesquiterpenes isolated from yarrow display anti-inflammatory properties through inhibition of COX-2, an enzyme involved in inflammation and pain (Applequist & Moerman, 2001; Benedek & Kopp, 2007). Extracts of four Achillea species, including the Achillea millefolium species found in the Flathead National Forest, showed a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity against seven different strains of pathogenic bacteria and fungi (Saeidnia et al., 2011). The aromatic, delicately feathered leaves and cloud-like flower heads of yarrow contain compounds for a familiar and ever-present need: wound-healing.

St. John’s Wort: revered and reviled

St. John’s Wort, Hypericum perforatum, is native to Eurasia and North Africa, but is now so common in North America it is often considered a noxious weed. The showy, yellow flowers and glandular leaves contain numerous bioactive compounds that are harmful to grazing animals but prove useful for human medicine. St. John’s Wort was used in traditional Chinese, Greek, and Islamic medicine for depression, anxiety, nerve pain, wounds, infections, and inflammation (Barnes et al., 2001). The scientific genus name, Hypericum, is ancient Greek for “above” (hyper) and “picture” (eikon). “Above picture” refers to the tradition of hanging the revered and powerful plant over religious icons (Barnes et al., 2001). The common name, St. John’s Wort, originates from the practice of harvesting the plant during the Midsummer festival, later Chirstinaized as St. John’s Feast Day. Harvesting the flowers at such an auspicious time was believed to make the herb’s healing and magical powers even more potent (Trickey-Bapty, 2001). On the festival day, St. John’s Wort was hung over doorways to ward off evil spirits. This practice inspired another common name: “fuge daemonum” (demon-flight).

Fields of the tall yellow flowers, which excrete a rusty red compound when crushed, are a familiar site along disturbed roads, old logging sites, and burns here on the Flathead National Forest. The plant’s bioactive compounds give it both medicinal properties and also invasive advantages, since the plant engages in allelopathy and releases chemicals into the surrounding soil that inhibit other species’ germination and growth (Aziz, 2006). Chemical analysis reveals two significant bioactive compounds, hypericin and hyperforin, that support several of the traditional uses of St. John’s Wort (Barnes et al., 2001). Hyperforin appears to inhibit serotonin uptake, analogous to conventional selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as well as inhibit the uptake of other neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine (Barnes. 2001). These antidepressant activities are substantiated in randomized controlled studies where the herb is more effective than a placebo and as effective as several conventional antidepressants in mild-to-moderate depression (Barnes, 2001). Hyperforin shows significant antimicrobial and antifungal effects as well as increased collagen synthesis which expediates wound healing (Nobakht, 2022).

A family of pungent herbs: the Mints

One of the oldest surviving medical texts in the world, the ancient Egyptian Ebers Papyrus from 1550 BC, recommends mint for stomach pain and flatulence (Pickering, 2020). The Salish and Kootenai as well as the Blackfeet used a local mint family member, Monarda fistulosa (Beebalm), for stomach pain, toothaches, colds, and fevers (Anderson; Hart 1979). Monarda fistulosa contains thymol, a strong antiseptic, with a cooling, strong flavor and odor that is popular today in mouthwashes and toothpaste (Lawson et al., 2021). The Salish rubbed Monarda fistulosa on the body for a mosquito repellant and sprinkled dried leaves on meat and berries to repel flies and preserve food (Bear Don’t Walk, 2009). The antimicrobial activity of the plant is attributed to terpenoids that slow the growth of certain pathogenic bacteria, like Streptococcus aureus (Anwar et al., 2019). Members of the mint family include an array of herbs such as beebalm, self-heal, horsemint and thyme that caught the attention of people as possessing the revered ability to heal.

Many cultures throughout the ancient and indigenous world recognized the medicinal properties of Yarrow, St. John’s Wort, and mint. The long-standing importance of these plants in the human story explains their persistence as daily shapers of our world today.

References

Anderson, M. Kat. “Wild Bergamot.” United States Department of Agriculture. https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_mofi.pdf

Anwar F, Abbas A, Mehmood T, Gilani A-H, Rehman N. Mentha: A genus rich in vital nutra-pharmaceuticals—A review. Phytotherapy Research. 2019; 33, 2548–2570. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6423

Applequist, W.L., Moerman, D.E. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.): A Neglected Panacea? A Review of Ethnobotany, Bioactivity, and Biomedical Research1 . Economic Botany 65, 209–225 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-011-9154-3

Azizi, M. and Fuji, Y. (2006). ALLELOPATHIC EFFECT OF SOME MEDICINAL PLANT SUBSTANCES ON SEED GERMINATION OF AMARANTHUS RETROFLEXUS AND PORTULACA OLERACEAE. Acta Hortic. 699, 61-68 DOI: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.699.5 https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.699.5

Barnes, J., Anderson, L.A. and Phillipson, J.D. (2001), St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): a review of its chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 53: 583-600. https://doi.org/10.1211/0022357011775910

Bear Don’t Walk, Mitchell Rose, “Recovering our Roots: The Importance of Salish Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Traditional Food Systems to Community Wellbeing on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana.” (2019). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11494. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11494

Benedek, B., Kopp, B. Achillea millefolium L. s.l. revisited: Recent findings confirm the traditional use. Wien Med Wochenschr 157, 312–314 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-007-0431-9

Chandler, R.F., Hooper, S.N. & Harvey, M.J. Ethnobotany and phytochemistry of yarrow, Achillea millefolium, compositae. Econ Bot 36, 203–223 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02858720

Hart, Jeffrey A. “The ethnobotany of the Flathead Indians of Western Montana.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 27.10 (1979): 261-307.

Lawson SK, Satyal P, Setzer WN. The Volatile Phytochemistry of Monarda Species Growing in South Alabama. Plants. 2021; 10(3):482. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10030482

Nobakht SZ, Akaberi M, Mohammadpour AH, Tafazoli Moghadam A, Emami SA. Hypericum perforatum: Traditional uses, clinical trials, and drug interactions. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2022 Sep;25(9):1045-1058. doi: 10.22038/IJBMS.2022.65112.14338. PMID: 36246064; PMCID: PMC9526892.

Pickering, Victoria. “Plant of the Month: Mint.” JSTOR Daily, 1 April 2020, https://daily.jstor.org/plant-of-the-month-mint/.

Ryan, Tim. “Ethnobotany of the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes.” Montana Native Plant Society Annual Meeting, 28 June 2024, Camp Utmost, Greenough MT. Lecture.

Saeidnia S, Gohari A, Mokhber-Dezfuli N, Kiuchi F. A review on phytochemistry and medicinal properties of the genus Achillea. Daru. 2011;19(3):173-86. PMID: 22615655; PMCID: PMC3232110.

Trickey-Bapty C (2001). Martyrs and miracles. New York: Testament Books. p. 132. ISBN 9780517164037.